Peace Meal Supper Club™ #14 is offered as a woefully small but deeply respectful expression of gratitude to the unconquerable Worker.

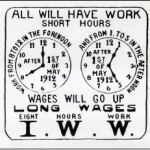

We speak often of the American Labor Movement as that which brought us the weekend and the eight-hour workday. This attribution is correct, although these benefits were not granted all in one sweep of corporate largesse. These present-day taken-for-granteds in no way represent the magnitude of what Workers have gifted us. Nor do they indicate the fierceness of the fight.

We speak often of the American Labor Movement as that which brought us the weekend and the eight-hour workday. This attribution is correct, although these benefits were not granted all in one sweep of corporate largesse. These present-day taken-for-granteds in no way represent the magnitude of what Workers have gifted us. Nor do they indicate the fierceness of the fight.

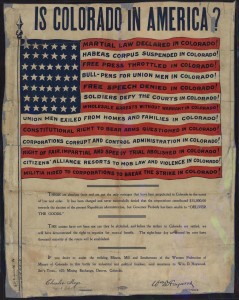

Reading about Labor’s struggle from the late 1800s and up to 1937 is like reading propaganda–even the non-biased accounts read as sensational. Charges of conspiracy and insurrection were leveled against Workers as they sought fair wages and safe conditions. Federal militia and citizen’s armies were sent in to quell alleged anarchist rebellions, atheists were thrown out of court, and our nation was on the brink of destruction due to socialist machinations, it would seem.

Ironically, it has been The Establishment–that amorphous mix of corporation, judiciary, law enforcement, press, and legislators–that has invoked the voice of propaganda. From the earliest struggles, Workers have been classified as insurrectionists, anarchists, socialists, communists, atheists, and terrorists. While some indeed have been–just as among any group of the citizenry we can find a spectrum of “-ists”–these labels have been used to justify violent suppression of even the most basic demands.

Ironically, it has been The Establishment–that amorphous mix of corporation, judiciary, law enforcement, press, and legislators–that has invoked the voice of propaganda. From the earliest struggles, Workers have been classified as insurrectionists, anarchists, socialists, communists, atheists, and terrorists. While some indeed have been–just as among any group of the citizenry we can find a spectrum of “-ists”–these labels have been used to justify violent suppression of even the most basic demands.

Hysteria aside, Labor has been a powerful progressive force, a cornerstone of social justice, the factory floor whereupon the betterment of society was wrought. Labor has never been one to move backwards. It has been pushing society forward since the 1600s.

The first known legal case in the United States (Commonwealth v. Pullis) involving a strike to raise wages occurred in Philadelphia in1806. The court’s decision was that striking workers were conspiring illegally, a conclusion significantly colored by English common law. A few decades later, in the 1842 case Commonwealth v. Hunt, the Massachusetts Supreme Court determined that labor combinations–unions–were not inherently illegal, provided their activities were legal. The significant ‘gray area’ in this decision led to inconsistent application through the following decades, and provided ample reason for employers to press the state of intervention in employee disputes. “Interfering with private enterprise” became synonymous with “threatening to overthrow the government of the United States.” Workers were not seeking livable wages; they were anarchists determined to destroy the established order. It doesn’t take much effort, then, to bring in the military. Which is what happened repeatedly during the 60-year period from 1870 to 1940.

John Siney, who attempted to organize coal miners in Pennsylvania in the 1870s, was arrested under charges of conspiracy. During his trial, he challenged the court: “We have been called agitators, we have been called demagogues, because we have counseled our members to try and secure better wages and harmonious settlements. Is it wrong to teach men to seek a higher moral standard? Is it wrong to advance our financial interests? If so, let those who operate our mines and mills abandon the various enterprises to with they are engaged in the pursuit of wealth.”[1]

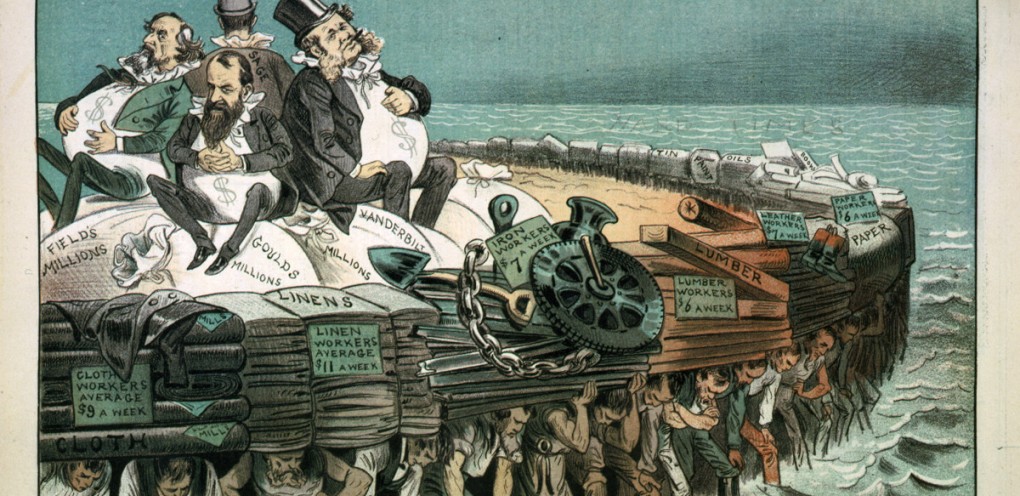

Those who operated the mines, mills, railroads, and factories were formidable foes: Carnegie, Gould, Pullman, Vanderbilt, Ford, Morgan. Driven by a fierce creed of capitalism, they amassed unprecedented fortunes as they built massive industrial empires. They were not ones to make humanitarian concessions to the workforce. In fact, they were quite contrary to the idea. They frequently made unannounced, drastic cuts in wages without regard to the livability of those wages. In some of the industries, mining for example, risk of injury or death was present daily. Worker safety was not among employers’ considerations across most industries, as is vividly portrayed in the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire in New York City, 1911.

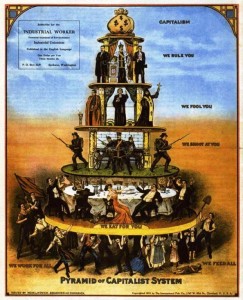

Labor historian Sidney Lens writes in The Labor Wars, “‘Under the natural order of things,’ said Herbert Spencer, ‘society is constantly excreting its unhealthy, imbecile, slow, vacillating, faithless members’ in order to leave room for the competent ones entitled to reward. Gould and Vanderbilt…operated on the simple thesis that the capitalists, by their proven superiority, were entitled to rule; the workers, by their proven ineptness, obligated to accept their judgments.”[2]

Labor historian Sidney Lens writes in The Labor Wars, “‘Under the natural order of things,’ said Herbert Spencer, ‘society is constantly excreting its unhealthy, imbecile, slow, vacillating, faithless members’ in order to leave room for the competent ones entitled to reward. Gould and Vanderbilt…operated on the simple thesis that the capitalists, by their proven superiority, were entitled to rule; the workers, by their proven ineptness, obligated to accept their judgments.”[2]

Such strong class-based bias, projecting an unflinching assumption of Worker subservience, supposes that the Worker is less worthy due to inherent personal, possibly genetic, qualities. This thoroughly reprehensible idea has been the impetus behind uncountable institutional crimes, from American slavery to British and American eugenics and rampant worldwide genocide in this century. America has focused such prejudice upon wave after wave of immigrants, from Jews to Irish to Italians to Mexicans, not to mention women of all origin, all of whom have successively comprised major portions of our workforce. It seems that once we concede constitutional rights to Workers, we chip away at them via other biases.

The rights we’re according Workers are the rights to which any human is worthy. Freedom of speech, the right to assemble, the right to peaceably demonstrate, the right to fair wages and equal treatment in the eyes of the law, the abolishment of child labor–these form the very core of the Labor Movement’s values, and therefore place it in the domain of basic social justice. Workers have shed blood for more than just pay and weekends.

For example, one of the most colorfully radical unions, the Industrial Workers of the World, waged a highly successful series of free speech campaigns between 1909 and 1917. The Spokane campaign in 1909–which you can read about here–exemplifies peaceful civil disobedience, the ability of a dedicated few to secure rights for all, and the tendency of the establishment to suppress speech deemed anti-religious or unpatriotic. As one demonstrator was arrested and pulled off the soapbox, another one would take his or her place–and they did this relentlessly. The jails were filled many times over, hundreds of speakers were beaten by police, fines were levied, unconstitutional and biased ordinances were passed, and still the Wobblies–as IWW members were called–continued their campaign. Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, an indefatigable feminist and future co-founder of the American Civil Liberties Union, even chained herself to a lamppost

For example, one of the most colorfully radical unions, the Industrial Workers of the World, waged a highly successful series of free speech campaigns between 1909 and 1917. The Spokane campaign in 1909–which you can read about here–exemplifies peaceful civil disobedience, the ability of a dedicated few to secure rights for all, and the tendency of the establishment to suppress speech deemed anti-religious or unpatriotic. As one demonstrator was arrested and pulled off the soapbox, another one would take his or her place–and they did this relentlessly. The jails were filled many times over, hundreds of speakers were beaten by police, fines were levied, unconstitutional and biased ordinances were passed, and still the Wobblies–as IWW members were called–continued their campaign. Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, an indefatigable feminist and future co-founder of the American Civil Liberties Union, even chained herself to a lamppost

so she could prolong her speech. One demonstrator, when accosted by police, stated that he was merely “reading the Declaration of Independence.” The two-year campaign was successful, with the city restoring civil liberties and investigating the employers that were the subjects of the Wobblies’ speeches.

The violation of speech rights was joined by the curtailing of the right to assemble, notably during the steel strikes in Pennsylvania that began in 1919. Permits to assemble were required, the requests for which were subsequently ignored for months. Meetings that were held in spite of permits were disrupted by the use of police force. Private meetings were also invaded by the authorities, with new laws requiring that meetings be conducted only in English.[3] In another strike, one among textile workers in Lawrence, Massachusetts, Workers avoided arrest by choreographing their movements on the sidewalks and in retail shops, making their presence known but not being indictable for assembling ‘unlawfully.’ The IWW, ever creative in its circumvention of unconstitutional mandates, devised a “thousand mile picket line” by boarding trains and moving among the railcars to prevent transport of strikebreakers.[4]

The right to picket is considered a natural part of the right of assembly, yet picketers have long been subject to violent attack and shutdown by the authorities, extending to today’s demonstrations on behalf of other causes. One of the most horrific cases of violence against picketers was the Memorial Day Massacre of 1937, in which Chicago policemen fired into a line of picketers as they made their way to the gates of Republic Steel. A Paramount News photographer caught the incident on film. Paramount refused to show the film publicly, for fear of inciting a riot.[5] Watching it today, the scene seems all too familiar: peaceful citizens hoping to have their voices heard are brutalized by an over-eager paramilitary police force, which in this case was armed by the corporation.

Through over 200 years of labor strife in the US, the Establishment has routinely engaged in surveillance, infiltration, provocation, collusion, unconstitutional legislation, jaundiced judiciary, and racial fear-mongering. Federal troops and National Guardsmen have been utilized to ‘resolve’ problems between Workers and employers. Industrialists have been allowed to establish their own private militias. States have willingly performed executions. Rather than mediate settlements, state and federal governments have chosen to defend corporate interests. Corporate personhood was born in 1819, and came of age in 1888. Its position of primacy in our culture today is almost unassailable.

Workers, meanwhile, though far from faultless, have fought on behalf of constitutional rights for the less privileged. Among Labor’s champions we find leaders of other socially progressive efforts, ranging from women’s suffrage to racial equality. Workers have pooled their funds to provide for other Workers on strike; paid bail and legal funds; and financed burial and memorials for the casualties. During the particularly intense 1912 Lawrence Textile Strike, the IWW arranged foster homes for the children of strikers. This was considered an outlandish, media-grabbing gesture, but the children had been undernourished from birth, with a 50% mortality rate common among in the town. By providing better temporary conditions for the children, the union enabled the striking families to focus on the strike at hand and provided much needed medical care for the children. The Workers won a resounding victory in the form of increased wages, shorter hours, overtime pay, and other benefits.

The ability of Workers to conduct themselves peacefully during strikes–admittedly a long time coming–was exemplified during the Lawrence Textile demonstrations. Peaceful striking scaled another peak during the Sitdown Strike at a General Motors plant in Flint, Michigan, in 1936. The strikers did not leave the plant to picket outside. Instead, they remained peacefully inside for forty-four days. This kept the plant occupied and unable to take on strikebreakers. It also shielded the strikers from aggression. They established their own civil structure, had stringent regulations against substances and violent behavior, took care not to damage GM property or equipment, and kept the plant clean and sanitary. Food was allowed in by the authorities, and the heat was kept on. One attempt to take the plant by force was rebuffed, and ultimately the strikers were rewarded for their efforts. The strike has since served as a model of non-destructive civil disobedience and was a forerunner of ‘sit-in’ and ‘occupy’ techniques used decades later. It also presents an unusual restraint of force: Michigan Governor Frank Murphy had National Guardsmen at his disposal. He chose to use them to protect the strikers.

Murphy understood the very core of the Labor Movement, expressed very well by Washington Post editorialist E. J. Dionne: “The union movement has always been attached to a set of values — solidarity being the most important, the sense that each should look out for the interests of all. This promoted other commitments: to mutual assistance, to a rough-and-ready sense of equality, to a disdain for elitism, to a belief that democracy and individual rights did not stop at the plant gate or the office reception room.”

The relationship between government and Workers reached a more peaceful stasis when the National Labor Relations Act was signed in to law in 1935 by President Franklin Roosevelt. It marked a major victory for Labor, as it legitimized unions, Workers’ rights to bargain collectively for better conditions, and to strike when necessary. While far from complete–it excepted agricultural laborers, for example–it was a major milestone in moderating the relationship between employee and employer.

Not surprisingly it was hotly contested as unconstitutional, and numerous bills were introduced to limit its reach during the first 10 years of its existence. The now-standard cries of “socialism” and “threat to freedom” were levied against it, but it has stood. It was a sign of progressive change.

Robert La Follette, one of the great progressive leaders of the early 1900s, introduced Issue #1 of his periodical The Progressive thusly:

“In the course of every attempt to establish or develop free government, a struggle between Special Privilege and Equal Rights is inevitable. Our great industrial organizations [are] in control of politics, government, and natural resources. They manage conventions, make platforms, dictate legislation. They rule through the very men elected to represent them. The battle is just on. It is young yet. It will be the longest and hardest ever fought for Democracy. In other lands, the people have lost. Here we shall win. It is a glorious privilege to live in this time, and have a free hand in this fight for government by the people.”

That was in 1909, and by 1938 and the enactment of the Fair Labor Standards Act, democracy had indeed made progress. So where are we today? Have we truly garnered the victory he sought?

Among the larger industries, unionization has resolved the primary issues. Unions have perhaps become a bit complacent, charges which were leveled at the AFL in the early 1900s. Other unions have fallen due to factionalism or have simply become obsolete. Some, like the United Farm Workers, survive only to celebrate their own history.

So it is no surprise that more work is to be done. Recent exposés regarding Amazon’s corporate work culture indicate that the Gilded Age industrialist model is still alive and well. A review of the Fair Labor Standards Act shows that agricultural workers are exempted, and further research indicates that child labor is still allowed in farm fields. Minimum wage campaigns among food-workers serve to highlight the plight of others in service industries, and indeed all along the food supply chain. The H-2A guest worker program is rife with abuses.

So it is no surprise that more work is to be done. Recent exposés regarding Amazon’s corporate work culture indicate that the Gilded Age industrialist model is still alive and well. A review of the Fair Labor Standards Act shows that agricultural workers are exempted, and further research indicates that child labor is still allowed in farm fields. Minimum wage campaigns among food-workers serve to highlight the plight of others in service industries, and indeed all along the food supply chain. The H-2A guest worker program is rife with abuses.

Beyond our borders, we see more that needs our attention. In 2012, Bangladeshi garment workers suffered a brutal re-enactment of the 1911 Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire, in which American business–that is, Walmart–played a significant role. Cacao is over-run by child labor, though American corporations have vowed to fight this practice.

Coca-Cola, one of the most recognizable American brands, has been implicated in using paramilitary force in the deaths of union organizers in Colombia. Though a Miami district court dismissed the original case, ongoing inquiry reveals corporate actions similar to those among 19th Century American industrialists.

Along our border with Mexico, factories known as maquiladoras provide cheap labor for American goods. Working conditions are poor, living conditions substandard, and wages extremely low.

The American capitalist model has been exported worldwide. Wherever it goes, it takes with it a very old mindset. A major stockholder of American Woolen, around the time of the 1912 strike mentioned above, told prominent liberal minister Harry Emerson Fosdick: “Any man who pays more for labor than the lowest sum he can get men for is robbing the stockholders. If he can secure men for $6 and pays more, he is stealing from the company.”[6]

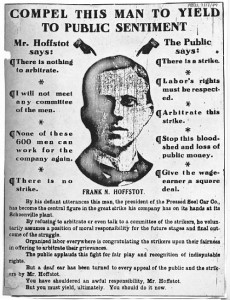

Over at the Pressed Steel Car Plant in 1909, company president Frank Hoffstot’s opinion was that “when all’s said and done” wages are fixed by “supply and demand. The same as everything else. We buy labor in the cheapest market.”[7]

And when things get tense, and workers rebel against low wages and substandard conditions, there is one sure-fire remedy. US Attorney General Richard Olney‘s prescription for curing the Pullman Strike in 1894 was to apply “force which is overwhelming and prevents any attempt at resistance.” It should be no surprise that Olney was a major railroad stockholder.[8] Have a Coke and a smile.

It is hard to study the Labor Movement and not view Capitalism as the fortress of cowards, who call upon the government to save them from the clutches of their underlings. Capitalism has continuously fought to curtail the constitutional rights of citizens, has infiltrated and provoked violence rather than deal fairly with those upon whose labor their empires rest, and has shown not one degree of conscience.

There is a ray of hope, however. In the words of Ayn Rand: “The moral justification of capitalism does not lie in the altruist claim that it represents the best way to achieve ‘the common good.’ It is true that capitalism does—if that catch-phrase has any meaning—but this is merely a secondary consequence. The moral justification of capitalism lies in the fact that it is the only system consonant with man’s rational nature, that it protects man’s survival qua man, and that its ruling principle is: justice.” So this will all be cleaned up in short order.

——————–

I am guilty of criminal neglect for not mentioning Bill Haywood, Eugene Debs, Walter Reuther, Mary Harris “Mother” Jones, and other stalwarts of Labor. The history I have given is unforgivably brief, and does not do justice to the innumerable deaths and injuries brought upon Workers by the forces of industry and government.

Please consider reading about the following events, or watching the brief videos.

The General Motors Sit-Down Strike, 1936 [9-minute video with historic footage]

The Memorial Day Massacre at Republic Steel, 1937 [article]

The Memorial Day Massacre at Republic Steel, 1937 [16-minute documentary; original newsreel footage; in 2 parts]

The Pullman Railroad Car Strike, 1894

The Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire, 1911

Sidney Lens. The Labor Wars: From the Molly Maguires to the Sit-Downs. Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2008.

[1] Sidney Lens, The Labor Wars: From the Molly Maguires to the Sit-Downs (Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2008), 26.

[2] Lens, 5.

[3] Lens, 202-210.

[4] Lens, 167.

[5] Lens, 320.

[6] Lens, 170.

[7] Lens, 160.

[8] Lens, 98.