We enter the theater and find it’s become a hall of mirrors, highly polished and meticulously disorienting. As we take our seats, we can’t tell the real from the carefully projected.

The lights go down and a softly strummed arpeggio summons the spotlight. Our man steps forward, surrounded by the reflections he is curating. As he speaks, we are still not sure which panel to watch. We are reflected along with him, as if the audience is also part of the performance.

“Early in the evening, she goes out,” he begins. Acoustic guitar, double bass, lilting piano, and the always-seductive brushed snare accompany his words, conjuring cocktails and a lightly wafting cloud of smoke. Our perception becomes elegantly clouded.

His next few lines not only increase our interest but elicit our doubts. She’s gone to see a friend, he readily pretends. “I’m not supposed to know,” he says candidly, indicating that he knows all too well.

Walter Hyatt’s “Blind Love Blues,” with its shifting identities and altered perceptions, resembles Ruggero Leoncavallo’s celebrated 1892 opera, Pagliacci. Leoncavallo’s play-within-a-play involves multiple levels of infidelity, confused identities, and clouds of suspicion. In the opera’s prologue, we are informed that the show is about real people. But with each actor performing multiple roles, we have to carefully watch for the reality.

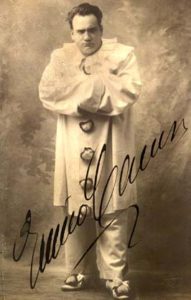

In the opera’s second and final act, lead character Canio, dressed as a fool in the grand tradition, storms the stage attempting to identify his wife’s lover. In “Blind Love Blues,” however, our leading man plays it closer to Leonard Cohen, whose resignation in “Famous Blue Raincoat” is almost unbearable. Acceptance tempered with grace lies at the heart of Walter Hyatt’s song, and within this respectable context he paces the mirrored hall in the costume of a fool—but certainly a sophisticated and self-aware one. As we listen to his concise story, we must discern his true identity. The song is deceptively simple on the surface but seductively complex once we discern the angle of the mirrors.

Carefully placed, mirrors show us only what we want to see. Simultaneously, they block out things we do not wish to see. That is perhaps their greatest purpose.

§

In his second stanza, Walter tell us that though his partner has strayed, “faith is hard to lose.” As if to bolster his statement, he tells us that she still comes home. He doesn’t indicate how frequently she does so, nor how long she stays. But this small gesture, however fleeting, counterbalances all of her other actions and is all the proof he needs.

Walter uses the word ‘faith’ where others might have used the word ‘trust.’ There is wondrous subtlety in this word choice, one which takes the song into much deeper territory. Trust is easily broken, often by one act of transgression. It is almost impossible to rebuild, since each of the transgressor’s subsequent actions can prompt suspicion. But faith is another matter. It does not depend upon the actions of another person, but upon our belief in who the other person is. It cannot be destroyed from the outside, but only from within ourselves. Destroying one’s own faith takes willingness and a fervent commitment. Walter isn’t ready for that yet.

Put another way, trust is tangible: the evidence, positive or negative, is all around. Faith is transcendent: the evidence is never to be seen.

Invoking faith, Walter sets up his camp in the holy land, where Jehovah refused to give up on Israel, in spite of so much infidelity, and where Israel refused to give up on Jehovah, even after 40 years of manipulation in the desert. Like true believers who will never give up on Jesus’ imminent return, Walter will never give up on his beloved. No amount of advice or persuading from others will matter. Some things you believe until you’re ready not to believe.

Religious faith provides present comfort leveraged against future hope and a grand purpose. Those who employ religion are willing to ignore its inconsistencies; this is simply the price of admission. Latent bigotry, endemic xenophobia, and extreme provincialism can be reflected, deflected, or completely obscured. God can harmonize all these dissonant strains. It is said that God created man in his image; and in this song, perhaps Walter sees God in his own reflection.

In his use of words like “faith” and “believe,” he clearly makes his love for his spouse into religious practice. By doing so, he has immunized it against our judgment.

§

The Christian apostle Paul stated, “Love is patient, love is kind. It does not envy, it does not boast, it is not proud. It is not rude, it is not self-seeking, it is not easily angered, it keeps no record of wrongs. Love does not delight in evil but rejoices with the truth. It always protects, always trusts, always hopes, always perseveres.”

Verging on self-sacrifice, perhaps love can also be considered co-dependent. Walter seems to play into this with a declaration in the fourth stanza: “I know I love her more than someone else.”

This condition, of loving her more than he loves someone else, can easily paint him as a victim. His attachment is so great that it overrides good sense and reason, making him vulnerable to whatever acts she might commit. He couldn’t possible love anyone else this much, and surely she loves him the same way. With love comes great sacrifice, so he’ll cinch up his belt of truth and shield himself with faith.

For him to seek vengeance or retribution would be self-serving. For him to keep track of her transgressions would be to love her less. His selflessness leads to sacrifice, which in turn leads to heroism—or is that a savior complex?

For there is a beautiful ambiguity in his “more than someone else” declaration, and in a song that trades heavily in subtlety, this line’s leverage is almost imperceptible. It sneaks by the listener and delivers one meaning, leaving the other to register later. Which is the mirrored image, and which is the real?

For he could be proclaiming that he loves her more than any other man could possibly love her, and in this we have an entirely different situation. His love is grand, powerful, and able to outlast the love of any other suitor. Now he truly is Jehovah to her Israel, and is confident that, when she realizes the impotency of the neighboring gods, she’ll gladly come back to his altar. Once there, she’ll realize the truth as he proclaims it: “I love her better than she loves herself.”

The bottom line is still the same: he endures in order to be her hero. He drives it home with one more nail: “I can stand the pain,” he says. “I just can’t stand to lose.”

Has his devotion just run into the weeds of narcissism? Is he in the play only to garner applause for his own performance? Has he created an alternate reality for the sole purpose of winning? If so, she is no longer a straying partner, but a game piece, demonstrating daily the grandeur of his love.

No matter how bad she gets, he can always supply more love than is humanly possible. He aims to win. The ruse is up, we’ve identified our man.

§

Our man’s stoic stability stands in sharp contrast to the fretting of Tony Villanueva, writer and singer of “Lover’s Lie,” a 1997 song by the Derailers. Tony’s anxiety is well out front, goading his denial.

“I have every right to ask questions,” he says, “but I’m not one to pry.” When faced with a situation like Walter’s, Tony is torn between wanting to know and wanting to stay in the dark. We get the sense that his world is about to collapse, whichever option he chooses. Walter, however, remains cool and collected.

Gary Stewart provides another contrast in his 1974 hit, “Drinkin’ Thing.” Filled with suspicion regarding his partner, he won’t ask her where she’s been. It’s not his reluctance to pry, but rather his fear that she will “probably tell the truth.” Walter clearly knows the truth, so asking would be redundant, not to say rude, and her answers would make very little difference. The beauty of not asking is not having to manage all the messy, capricious details. You only have to manage not asking.

§

Sketched with economic candor, “Blind Love Blues” leaves a lot unsaid. Walter’s taken great care to exonerate his beloved. He’s attributed her infidelities to his own mistakes, as he says in the second stanza: “I see the part I’ve played.” But he provides no details about what he has done. He won’t dish any dirt on her, either. He prefers to carefully adjust the mirrors to reflect her guilt upon himself, and leave it at that.

His reticence is a noble departure from a tradition in which the unfaithful are soundly lambasted. Dave Davies, in the Kinks’ song “Creeping Jean,” expresses utter contempt and disgust with his faithless lover’s “dirty friends and underwear.” He declares that she is, in fact, “a disease.” In Jason and the Scorchers’ incendiary “White Lies,” Jason Ringenberg’s voice is roiled by repulsion at the evening activities of his own friend-visiting Jezebel. Not content to defame only one cheating female, Robert Johnson, in “From Four Till Late,” unkindly generalizes that a “woman is like a dresser, some man always ramblin’ through its drawers.” Walter, ever the gentleman, will not speak ill of those not present.

As for his own mistakes, the easiest conclusion for us to make is the one Walter leads us to: his infidelities provoked hers. She has the right to get even; revenge is a tradition as old as infidelity itself. In the very noncryptic “While You’re Cheating on Me,” the Louvin Brothers sing, “For when you were faithful to me I cheated on you.” They are patient to wait out their tit-for-tat comeuppance, but don’t leave it up to fate entirely. While she’s out cheating, they’re home praying.

Walter’s slight admission of guilt does nothing to tarnish his god-like love, for even Jehovah repented now and then. In the absence of any contrary details, we know only that he is a long-suffering, possibly redeemed spouse of an unfaithful woman. To avoid our harsh judgments of her and to reduce our incredulity of his patience, he’s shrouded the whole affair in supernatural love. And as if divine love were not enough, Walter also invokes the world’s colloquial wisdom. “Wise men say that love is blind.” Or perhaps it’s a reflection of what we wish to see.

Risking narcissism to absolve the guilt of another might not be the answer for everyone. Back at the opera, Canio, in his clown-go-to-meeting clothes, rampages the boards trying to suss his wife’s paramour. In a startling confusion of life and art, he breaks character and murders his wife onstage. The last line of the performance declares that the comedy is over, for in fact, the denouement is quite tragic.

Walter, however, declares the tragedy over. He pursues a resolution more apropos classical comedy, one in which the hero’s state improves over the course of the play. He has provided his own deus ex machina, and now stands alone as the reflection of cumulative infidelities, the noble and heroic effect of purposefully hidden causes. And certainly no one’s fool.