My brother and I sat on the front stoop, with impressively out-of-tune plastic guitars in our hands. With sibling harmony decades removed from the Louvins, we proudly proclaimed, in front of god and everybody, things we couldn’t possibly have understood.

I was six, he was nine. The song we sang was “Your Cheatin’ Heart.”

People stopped to listen, remembers my brother. It could be that we were charismatic beyond our years, two prepubescent Elvises commanding the attention of all passersby. Or it could simply be that our audience was amused, just as I am now, by the dichotomy of life in a Bible-brandishing nation.

I was raised in a traditional, Christian, conservative home, firmly docked in the blue-collar mainstream. A scion of generations of preachers, I went to church three times a week. I was not sure what adultery was—except that it must be reserved for adults. Yet there I was, bellowing at the top of my lungs about a wife’s infidelity and the miserable night of judgment that she was enduring.

It’s fitting that such a contradiction was fostered by Hank Williams, a man whose personality was so complex that he had to establish an alter-ego just to manage it all.

§

“Your Cheatin’ Heart” paints a dire picture: An unfaithful woman finds herself tormented by her own heart, during a seemingly endless night. She can’t sleep, she can’t sit still, she can’t stop crying tears of remorse. Heartbroken by her own actions, she can only pace around her room, calling the name of the man she did wrong.

As for the man himself, all he can do is predict deepening despair for her. Tonight, she’s certainly tossing and turning, crying out for him; this will soon give way to cravings for his love, immersing her more deeply in the blues. That’s as happy as the ending gets.

There is one shared experience between them: “You’ll walk the floor the way I do,” he tells her. Possibly, they have different motivations for wearing out the linoleum: For her, it’s the pain of her guilt. For him, it’s the sting of being done wrong.

In the lyrics’ austere narrative, we get the sense that he’s content to let her heart torment her. He doesn’t relish condemning her, and her pending collapse doesn’t bring him any satisfaction. He’s simply telling her, almost clinically, what happens in these situations. There is a sense of knowing behind his words.

Her life crashing down in an eternal, sleepless, apocalyptic night might happen only in his imagination. His claim of “the time will come when you’ll be blue” is only a prediction. He could be dead wrong on that.

In truth, she might not have had one unrestful moment. But it’s obvious that he has.

§

A model of economic poetry, “Your Cheatin’ Heart” contains only 117 words. Fifty-eight of them are used in the two repetitions of the chorus. The song has only three words consisting of more than one syllable: cheatin’, away, and fallin’. Dr. Seuss could hardly make it easier to read.

If it didn’t focus on matters of the heart, we could be dismissive about its status as poetry. Yet it transcends its simplicity, for Williams, as all good poets, had a command of the words he knew. His literacy was no match for Shakespeare’s, but he was on equal footing when it came to understanding the soul.

Whether consciously or unaware, Williams frames his message in a non-durational, future tense. In so doing, he’s made the night seem perpetual. It’s not just tonight or tomorrow night. It’s a relentless lifetime of nights.

When the word day finally appears, it’s only as a marker of time. That day is far from cloudless and bluebird-filled. Rather, it brings another curse: She will pine and crave his love. Pining is leagues deeper than wanting, a significance that would be clear to Williams, with his roots in southern vernacular. She would yearn endlessly for something that was no longer attainable. He is clearly not taking her back.

In concert with his stark lyrics, Williams’ delivery is visceral, naked, and unpretentious, yet it is far from unadorned.

There is a harrowing quaver in his voice, borne not of uncertainty, but from hard-earned cataclysmic fear. He sings as if he’s just had the very literal Hell scared out of him by an Alabama fire-and-brimstone preacher, expounding the darker side of the gospel. He underscores his pronouncements by elaborating each line’s ultimate word, stretching out the vowels and lingering on the consonants m and n. These nasal constrictions provide the ubiquitous moan behind his blues.

As a vocal stylist, Williams has had many followers but few peers. His attention reaches deeper than a phrase or a word, expressing itself syllable by syllable. The elongated finish he applies to some words is matched by his halting delivery on others. This serves to create tension and imbalance, a clear portrait of his own suffering.

As music writer Cub Coda states, “Williams’ vocal is filled with regret and recrimination, coming from the bleakest of feelings, absolutely brimming over with despair.”

From his first utterance of the word make it’s obvious that he’s holding back his emotions. It matters little whether he’s filled with misery at his own state, or with pity for hers. There are plenty of heartaches and tears to go around, as indicated by his following the word weep with the phrase “cry and cry.” A less confident poet might edit such repetition. Williams self-assuredly resisted such editing, however. He knew that repeating the right word at the right time added incomparable impact. For example, to refer to a “Cold, Cold Heart” as a ‘very cold heart’ would leave it eviscerated.

From the opening liquid twang of Don Helms’ steel guitar, the Drifting Cowboys support every intonation of Williams’ voice. The song is resplendent with pathos.

§

Leonard Cohen is justifiably impressed, as he indicates by placing himself below Williams in the “Tower of Song:”

I said to Hank Williams, How lonely does it get

Hank Williams hasn’t answered yet

But I hear him coughing all night long

A hundred floors above me

In the Tower of Song

Cohen’s portrayals of extra-marital entanglements are complex, such as in “Famous Blue Raincoat,” wherein he expresses thanks to his partner’s lover for taking the sorrow from her eyes. While Williams’ relationships were also comprised of many overlain triangles, his representation of them is positively Spartan.

Songs by Cohen, Dylan, and similar singing poets can demand a great degree of deciphering, but Williams’ art is direct enough to be understood by all. In visual terms, his songs are more like Wyeth’s “Christina’s World,” and less like Pollack’s “Blue Poles #11.” We don’t have to stand mystified by a cubist’s alternate reality or by the angels of Chagall. It’s obvious what is being said. And in its way, void of veneer and obfuscation, Williams’ approach requires more of us, for we have to look unflinchingly at real life, acknowledging its potential for shame. His art embodies stark, stoned-in-the-gutter minimalism, a grimace in the glow of the tavern lights.

Likewise, he didn’t dull his pencil with metaphors. He kept it sharp and took deadly aim. “Your Cheatin’ Heart” contains a lone but wondrously efficient simile. As stark in its construction as is the remainder of the song, it compares her tears to the rain. With his relentless references to weeping and crying, by the time this simile appears we understand this is not the ordinary teardrops-as-raindrops comparison. We’re looking at a biblical deluge.

Like most folk art, this song is backed by a philosophical understanding. At its core, “Your Cheatin’ Heart” magnifies the heart as if it were the sum total of the person. It is a living, breathing conscience, standing in the center of the being, evaluating every misdeed, and mandating the appropriate punishment. But it’s not really that simple: With an Escher-like sleight of hand, the heart is also held responsible for the very desire to cheat. The heart is the instigator, snitch, prosecutor, and persecutor. It’s unrelenting. Just like those tears.

§

Aristotle considered it important that there be a certain distance between the work of art on the one hand and life on the other; we draw knowledge and consolation from tragedies only because they do not happen to us. It is important, however, that the observer be able to identify with the text across this distance. If this doesn’t happen, then we cannot empathize with the characters. In short, the play or song must be both distant and recognizable.

When a stylist such as Ray Charles or Beck Hansen records “Your Cheatin’ Heart,” it is evident that they are removed from the tragedy itself. They sing it as interpreters or commentators, but not as participants. As Williams’ alter-ego Luke the Drifter might term it, they are only describing a “Picture From Life’s Other Side.” Williams, however, lived on that other side every day of his life.

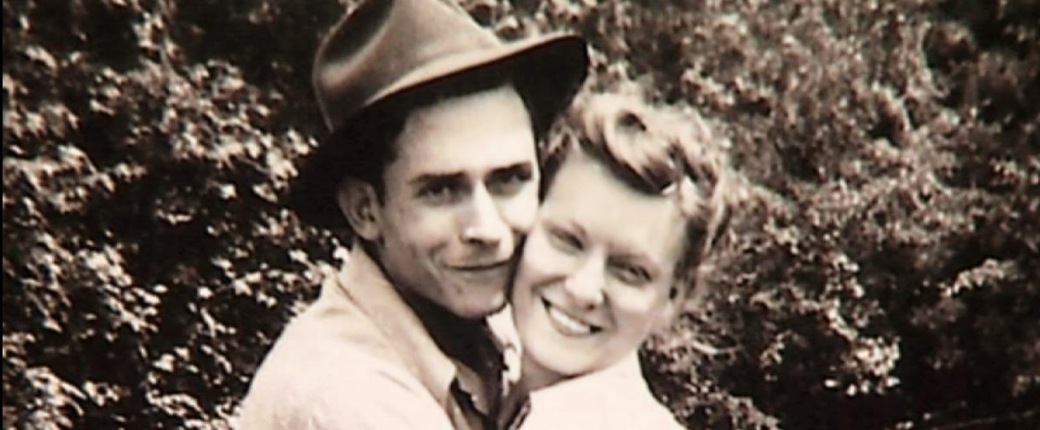

Legend has it that Williams wrote the song following a suggestion from Billie Jean Jones, his second wife, that he write something about how Audrey Mae Shepherd, Wife Number 1, cheated on him. He dictated the words to her as they drove around town. Audrey, however, maintained that Williams wrote it about the misery his own heart was giving him.

Their mutual infidelities are the stuff of daytime television, not to mention country songs. Hank wasn’t faithful on the road, nor was Audrey faithful in the town. Williams’ struggles with his unfaithful wife—and his own darker tendencies–inspired many of his songs. “The news is out all over town, that you’ve been seen out running around,” he sings in “You Win Again.”

Apart from cheating, domestic unrest was also prevalent. “Why Don’t You Love Me Like You Used to Do,” “Why Should We Try Anymore,” “I Just Don’t Like This Kind of Livin’,” and “You’re Gonna Change or I’m Gonna Leave” stand in the core of his canon. The titles call to us like tabloid headlines.

Williams did have songs that reflected the euphoria of love, too, such as “Settin’ the Woods on Fire,” in which he suggests they paint the town with their romantic fervor. “Comb your hair and paint and powder/You act proud and I’ll act prouder/You sing loud and I’ll sing louder/Tonight we’re settin’ the woods on fire.” But gleeful celebrations too often succumbed to the steamroller of reality: Williams and his partners were simply too dysfunctional to make it last.

Lucky for Williams, he had not only tailored suits and a fine Martin guitar, but a gift for putting his life into meter. He also had a shepherding manager and a recording contract. While he missed many live performances—either due to his physical absence or his inebriation—his truancy was offset by his reliability in the studio. He was jukebox gold, and his records sold by the millions.

Audrey, although she was a major factor in Williams’ success, hadn’t similar talents. The duets she recorded with Williams are models of a warring partnership. Country biographer Colin Escott writes: “Her duets with Hank were like an extension of their married life in that she fought him for dominance on every note.” Or as Williams himself said above: “you sing loud, and I’ll sing louder.” Loud was the only way she could sing, and that came through sacrificing pitch and control. She simply hadn’t the voice to carry her counter-propaganda.

Hank’s version of their story prevailed. And as if she needed it to get worse, soon major pop stars were crooning about her infidelities, and a movie loomed on the distant horizon.

§

Leo Tolstoy described art as a use of indirect means to communicate from one person to another. In a particularly creepy example of this, “Your Cheatin’ Heart” was released shortly after Williams’ death on January 1, 1953.

Says Nathan Rabin, of the AV Club: “Williams’ passing adds immeasurably to the haunting, almost ghoulish nature of the song; it’s as if he’s accusingly pointing a bony finger from beyond the grave, getting in one last good kick in his longtime war of wills and words with Audrey.”

In this context, the characteristic moan in Williams’ voice is amplified by the chill of death. His lyrics are a harbinger of judgment to come, grounded in his own after-life torment, validating all the Fundamentalist warnings he’d known from childhood. His warnings from the grave are wholly compassionless. Apocalypse is a dish best served cold in a diner on the Lost Highway.

Cohen adds relish: “You’ll be hearing from me, baby, long after I’m gone/I’ll be speaking to you sweetly from a window in the Tower of Song.”

§

“Your Cheatin’ Heart” and its writer weren’t the first in any category. The marriage of cheating and country blues existed long before Hank Williams sharpened his first pencil, as in songs like the wildly successful “Frankie and Johnny,” a genre-hopping hit for Jimmie Rodgers in 1929.

A heavy influence on Williams, Rodgers had already fused hillbilly, gospel, jazz, blues, pop, and folk styles, and was a bona fide superstar. He wrote many of his best recordings, and was able to relate with the common people. He felt what they felt, thought what they thought, worked the railroads, and died young of tuberculosis. Through his recordings, he proved the commercial viability of country music.

Vernon Dalhart, who mastered opera, pop, and country, had already set a high-water mark for record sales. His 1924 rendition of “The Wreck of the Old 97” was the biggest selling non-holiday record during the first 70 years of recorded music. The Carter Family also preceded Williams with their singer/songwriter ethic, aided greatly by the nationwide reach of legendary border station XERF.

The difference with Williams was the depth of his darkness, and his ability to articulate it with more grit and guts than his predecessors. His was not a good-natured confession of “I’m a rounder,” but a rather curdling acknowledgment that “I’m a wretched sinner.” He laid his soul bare in a way that transcended his class and origin.

Another advantage Williams enjoyed was having a pop music veteran, Fred Rose, act as his publisher, manager, and producer. Through Rose and other A&R men like Jerry Wexler and Mitch Miller, Williams sold his songs to a large variety of pop singers.

Joni James, with Williams’ sanction, was the first pop artist to record the song. Eerily, she recorded it on the day of his death. Her version reached Number 2 on the Billboard pop chart in 1953. Frankie Laine soon followed suit, as have Ray Charles, Patsy Cline, Elvis Presley, Louis Armstrong, Glen Campbell, Jerry Lee Lewis, Fats Domino, Van Morrison, Don McLean, Beck Hansen, and anyone who’s ever stepped onstage in a disreputable—and therefore self-respecting—honky-tonk.

While Williams’ legend grew, someone had to collect the royalties. The terms of their divorce had already promised half of them to Audrey. She later secured, for $30,000, the right to use the title “Hank Williams’ Widow.” She also established herself as a behind-the-scenes force in the industry: music publisher, booking agent, label owner, talent agent, and touring all-star show woman. She even served as a consultant on the 1964 film of Williams’ life, “Your Cheatin’ Heart.”

Williams might have delivered the final word with no chance for a formal rebuttal, but Audrey held the option of laughing all the way to the bank.

Hank’s cumulative portrayals of Audrey suggest that she had never listened to a word he had said. She developed a reputation for out-of-control emotions and substance abuse, as if she hadn’t witnessed the slow death of her ex-husband. Forty-two years after Hank died, Audrey herself died—one day before the IRS was scheduled to repossess her home.