The humble seed is the very antithesis of capitalist production: It will produce goods without the application of labor. It is abundantly self-regenerating. It is available to and reproducible by everyone, and it is freely-giving without regard to the market. It is the embodiment of diversity and social progress. It mirrors our own best behaviors.

It is a powerful force against rampant consumerism: it will prevent people from buying other products. And for this very reason, our economic system has been warring against the seed for almost 200 years. This should grate against our own best instincts.

Janisse Ray muses elegantly and personally about the seed in her recent book, The Seed Underground: A Growing Revolution to Save Food. Her book serves as a reminder of our existence outside the pulsations of commerce, of the strength we possess in our ability to carry culture, preserve life, and celebrate unconstrained forces. She understands that even during their dormant seasons, seeds are still powerful.

“Furthermore, between growing seasons, the seeds had to be traded, because traditional societies understood that, as in human reproduction, plants do better by outbreeding. To swap seeds is to keep a variety strong and valuable–a genetic currency, the exchange of priceless genetic material. How interesting that the agrarian within us understands that to survive, to keep our food crops viable, we have to be openhanded. Seeds have a built-in requirement for generosity. Otherwise, they suffer inbreeding.”[1]

Yet this generosity has been heavily compromised by a system that we, the people, no longer control. Capital, as a force, lies in the hands of the few. We, the many, are subject to its relentless pursuit of commodity-forms–which it will own and will gladly sell back to us. The modern story of seed is a study in political economics.

Jack Ralph Kloppenburg, Jr., explores this avenue in First the Seed: The Political Economy of Plant Biotechnology. A book of daunting scope, it illuminates the impulses that have provided us with seeds that work against us.

The urge of capital towards universal commoditizing once stopped at the farm gate. Farms were once islands of self-sufficiency in an ocean of increasing consumerism. Farmers grew their own seeds. They plowed with animals which could reproduce themselves; fertilized their lands with the manures from these animals; fed the animals with hay produced on the farm. It was a strong and self-sustaining model, not without its challenges and certainly not fail-proof. But the model was robust and well-developed, having provided the basis of agrarian society for millennia. Until the 1900s, farms remained the impenetrable anomaly in capitalistic America.[2]

The primary obstacle was the seed: it regenerated itself, multiplying with vigor the seed that preceded it. There was no need to purchase its replacement. In order for capital to conquer the seed, they had to disable its internal and external means of production. They had to alter the seed and those who used it.

“The growth of capitalism necessarily entails the destruction of modes of production based on the personal labor of independent producers.”[3] The effects are far-reaching.

As Marx observed, “The bourgeoisie cannot exist without constantly revolutionizing the means of production, and thereby the relations of production, and with them the whole relations of society. Conservation of the old modes of production in unaltered form, was, on the contrary, the first condition of existence for all earlier industrial classes. Constant revolutionizing of production, uninterrupted disturbance of all social conditions, everlasting uncertainty and agitation distinguish the bourgeois epoch from earlier ones.”[4]

This state of constant change is why we are endlessly presented with new cars, phones, blenders, computers, staplers, mops, toilet brushes, and innumerable other products. It really makes no sense: We have an economic model which requires that we constantly have to make products. When we exhaust all possibilities, we still have to make products. And when we’re saturated with products, we find other markets to sell our products. If we see something that is available for free–water, for example, or a seed–we must find a way to productize it, because our economic model will not allow for free stuff. That is the genetic urge of capitalism.

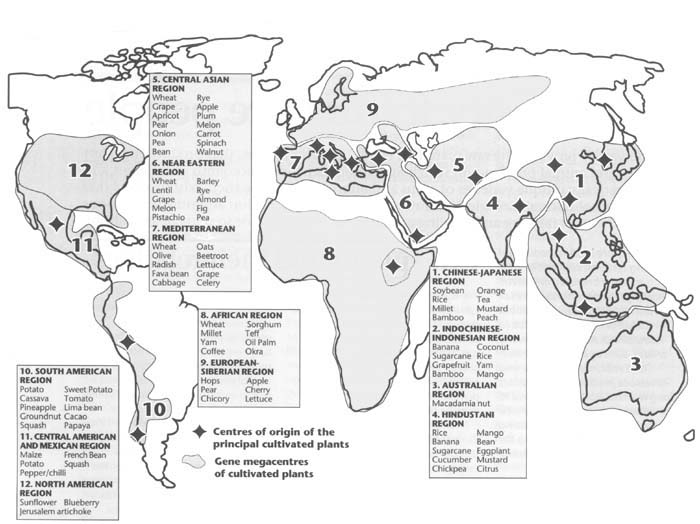

Seed has always been a critical resource for the United States. The region we inhabit is the native home of only five crops of economic importance: sunflowers, blueberries, cranberries, pecans, and the Jerusalem artichoke. The greater American crops–corn, squashes, beans, tomatoes, and dozens more–have origins south of our borders. Centers of origin are important, for they provide genetic diversity upon which civilizations flourish.[5] Though many crops had made their way northward before the coming of the Europeans, they passed through multiple bottlenecks along the way.

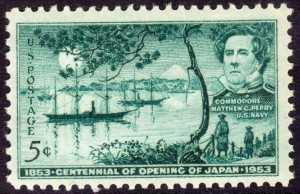

In the early 1800s, the United States began a program of global seed collection. They scoured the planet, under the direction of the US Patent Office and the Navy. The collection of diverse crops, to augment what the settlers brought with them, was considered a matter of national importance. Our survival as a nation largely depended upon our ability to supply ourselves with a diverse and resilient larder.[6]

Global collection of germplasm–a term used to describe the genetic packet within the seed–has never stopped. We are still engaged in large-scale collection of plant genetic matter. At times it is under the banner of national security, as in the programs of the early 1800s; other times it is under the flag of imperialism. Sadly, it is frequently operating under the aegis of humanitarian aid.

Under the early Patent Office program, Naval Commodore Matthew C. Perry made a series of “diplomatic missions” to Japan in 1853 and 1854. Best known for opening Japan to American trade, these missions brought the U.S. a tremendous variety of seeds. Perry’s foray is interesting for several reasons: it was overtly imperialistic, aimed at opening Japan for the U.S.’s own commercial benefit. Perry’s boats were armed with the most advanced guns available and he refused to leave their waters. He threatened to destroy towns along the harbor if he was not received. Japan had little choice but to cooperate. Such military-led acquisition of raw materials and the opening of new global markets should ring unpleasantly familiar to us today.

Regardless of their provenance, seeds from around the globe provided American agriculture with a solid foundation, “the product of thousands of experiments by thousands of farmers committing millions of hours of labor in thousands of diverse ecological niches over a period of many decades.”[7]

“The global distribution and transfer of PGRs (plant genetic resources) have been and still remain crucial elements of the political economy of plant biotechnology,” says Kloppenburg.[8]

With so much plant matter at their disposal, American plant breeders began in earnest the adapting of crops to North American conditions. By the early 1900s, plant breeders’ rights had become an very volatile issue.

Connecticut plant breeders Edward M. East and Donald F. Jones lamented in 1919 that “the man who originates devices to open our boxes of shoe polish is able to patent his product and gain the full reward for his inventiveness. The man who originates a new plant gets nothing.”[9]

We can argue that an improved plum–as in Plant Patent 13, awarded posthumously to Luther Burbank–is not a new plant, only an altered version of an old plant, but we will ultimately lose that argument. For the Plant Patent Act was signed into law in 1930.

“The Plant Patent Act of 1930,” elaborates Kloppenburg, “had granted patent protection to breeders of novel varieties of asexually reproducing plants, and the seed industry had long lobbied for provision of similar legislation for plants that reproduce sexually. In 1970, this ambition was partially realized with the passage of the Plant Variety Protection Act, and capital has continuously sought to extend the reach of private property in germplasm.”[10]

Another favorable development for plant breeders and seed companies came in 1980, with a patent case involving an oil-eating bacteria. The Supreme Court ruled 5-4 in favor of the bacteria’s ‘creator,’ Ananda Chakrabarty. The ruling left sufficient opening for seeds to be tossed in.

The decision also opened up the possibility for plant breeders to utilize utility patents for their products. This powerful avenue allows for proprietary protection of not whole plants, but discrete attributes of a plant: DNA sequences, genes, cells, tissues, and seeds. These traits are then licensed for use. The licenses carry very rigid constraints and intimidating enforcement trends.[11]

Yet, with all this protectionism run rampant, the fact is that 75% of the world’s plant genetic diversity has been lost since the 1900s, as farmers move towards genetically uniform, high-yielding crops.

“A variety lost to seed saving is a variety lost to civilization,” observes Ray. She continues:

“Three things result from varietal decline. First is the loss to our plates and palates…Second is the loss of sovereignty over seeds and the ability to control our food supply. Third, there’s another scary reality to this. All the lost varieties did more than liven up the table and keep farmers independent. Varietal decline threatens biodiversity. We know this–the less biodiverse any system is, the greater the potential for its collapse. In shriveling the gene pool through loss of varieties and through the industrial takeover of an evolutionary process, we strip our crops of the ability to adapt to change and we put the entire food supply at risk.”[12]

We often don’t think of this, deluged as we are by abundant product choices in our supermarkets. But we must look behind the glamour of consumer product packaging and see the dwindling supply of natural food resources. Modern agriculture has brought us 150 crops. Traditional agriculture brought us about 7000.

Apart from the growers of uniform, high-yield crops, “Growers with farms of less than seven acres preserve diversity through networks of seed and knowledge exchanges,” Karl Zimmerer, a Penn State University geography professor told a conference of the American Association for the Advancement of Science.[13]

The protection of seed diversity remains resident among farmers who are people, not corporations. Just as it always has. As long as capital will let it.

In the background of all this varietal development and seed diversity loss are two much-embattled institutions, the USDA and the network of land-grant universities (LGUs), which first served primarily as agricultural schools. Both institutions have complicated histories, far too serpentine to include here. Kloppenburg provides an engrossing look at their establishment, their neutralizing by seed producers, and eventual subjugation to industry in First the Seed. His application of social divisions of labor and exploration of the domain of research are eye-opening. Equally informative is his examination of the threat posed to capital by LGUs and especially the USDA. What capital sees it occupies, however.

By 1909, the conquest of LGUs and their associated experiment stations was nearing completion. Speaking before a convention in Washington, DC, Kansas researcher H. J. Waters stated, “It has been a fundamental mistake to assume that the duty of the experiment station is solely or even principally to benefit the farmer directly. A larger responsibility rests upon it–that of making an exact science of agriculture.”[14]

He is appealing to business here, not the farmer. The science of which he is speaking is applied science, that concerned with making products.

As for the USDA, Secretary of Agriculture Earl Butz handed down its shiny new attitude for 1955: “Adapt or die, resist and perish…Agriculture is now big business. Too many people are trying to stay in agriculture that would do better some place else.”[15]

Those people being booted by Butz were farmers. Small farmers who held agricultural tradition in their hands. They were a lot like the farmers who now hold 75% of global seed diversity in their hands.

Apart from all the talk of patents and big business, the conversion of seeds to proprietary status has major social impacts. Some are local, some are global.

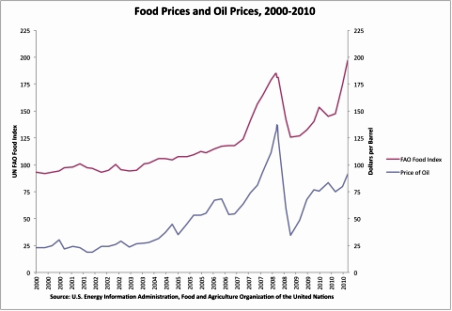

The people most directly affected are the farmers themselves–those that are left. They find that their entire business model has been converted from self-sufficiency to industrial dependency, as purchased inputs account for the bulk of their materials. Due to the required use of fertilizers, they are linked tightly to the petroleum industry, and suffer from the diminishing oil and gas resources. Debt is the norm, and it mounts in complex forms. And of course the seeds are now of the single-use variety, and come with licensing agreements.

For the farmers’ customers, things have changed, too. Food prices reflect petroleum prices. The many layers of labor involved add to the price increases. Quality is down. Choice is becoming more limited.

Larger social impacts ripple like a tsunami into all sectors of life: “These include the exacerbation of regional inequalities, generation of income inequalities at the farm level, increased scales of operation, specialization of production, displacement of labor, accelerating mechanization, depressed product prices, changing tenure patterns, rising land prices, expanding markets for commercial inputs, agrichemical dependence, genetic erosion, pest-vulnerable monocultures, and environmental deterioration.”[16]

In 1977, University of California-Berkeley plant physiologist Boysie E. Day addressed the American Society of Agronomy, and accepted the role of plant scientists in the social re-designing of America: “The agronomist has brought about the conversion of a rural agricultural society to an urban one. Each advance has sent a wave of displaced farm workers to seek a new life in the city and a flood of change throughout society.”[17]

It is chilling to consider that in its pursuit of commodity-forms and markets, capital has wrought wholesale changes in the social structure of the U.S. It is not unlike the very deliberate relocation of rural peoples to newly constructed cities currently underway in China, for the specific purpose of making them into consumers.[18]

The environmental effects are enormous, too, and are documented prolifically. One profound example regards the use of herbicides. While sellers of genetically-engineered seeds claim that less herbicide is required for these seeds, this claim seems to contradict the intended purpose of their developments. Roundup-Ready crops are specifically designed to endure the heavy application of Roundup. In fact, between 1996 and 2003, there was a 383 million pound increase in the use of herbicides in the U.S. This causes severe collateral damage to soils and waterways, hardly insignificant.[19]

Beyond our own societal transformation and agrochemical saturation, the effects continue to mount–specifically in the Third World, often with U.S. intention.

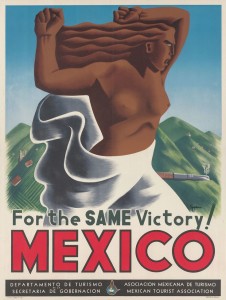

In 1941, U.S. Vice President Henry Wallace–previously he was Secretary of Agriculture–met with Rockefeller Foundation president Raymond Fosdick to discuss the benefits of targeted campaigns into Mexico. One scientist assigned to the project reported enthusiastically: “When the war is over, there will be millions to feed, large communities of people to be resettled, and farms to be supplied with seed, fertilizer, machinery, and livestock…the leaders of some of our large philanthropic foundations have become convinced that the best way to improve the health and well-being of people is first to improve their agriculture.”[20] In Germany, Great Britain, other war-torn parts of Europe perhaps. But Mexico?

Dr. Carl Sauer, geographer, author, professor, and champion of cultural diversity, warned against the program in 1941:

“A good aggressive bunch of American agronomists and plant breeders could ruin the native resources for good and all by pushing their American stocks. And Mexican agriculture cannot be pointed toward standardization on a few commercial types without upsetting native culture and economy hopelessly…Unless the Americans understand that, they’d better keep out of this country entirely.”[21]

The research centers that were established as part of the Rockefeller-funded program served dual purposes: they provided a mechanism for encouraging capitalist development in Third World countries, and they provided a conduit for greater transference of genetic materials from the Third World countries to developed nations.[22]

Kloppenburg highlights one critical aspect of this arrangement: “It is highly ironic that the Third World resource that the developed nations have, arguably, extracted for the longest time, derived the greatest benefits from, and still depend upon the most is one for which no compensation is paid.”[23]

All this genetic material finds its way into seed banks which are situated principally in the industrialized North. Global germplasm collection and free exchange have been considered within the principle of “common heritage.” It is the property of all mankind, across all barriers. This principle has been considered inviolate. However, the U.S. has indicated its willingness to violate this honored principle–claiming some germplasm as property of the U.S. Government–and has refused requests from Afghanistan, Albania, Cuba, Iran, Libya, Nicaragua, and the Soviet Union at various times.[24]

“If the U.S. now has a food weapon,” states Kloppenburg, “it is because nations such as Nicaragua, Ethiopia, Iran, and China have supplied the germplasm for its arsenal.”[25]

On this note, Janisse Ray’s indignation should be our own. Speaking of the aftermath of the U.S. invasion of Iraq, “by 2004, the U.S. put into place a new foundation of governance for the conquered Iraq: one hundred orders enacted by Paul Bremer, chief of the Coalition Provisional Authority. One of them was particularly strange. Under the heading ‘Amendment to Patents, Industrial Design, Undisclosed Information, Integrated Circuits, and Plant Variety Law,’ Order 81 authorized the introduction of GM crops and instituted intellectual property rights for seed developers. The order made seed saving of GM varieties illegal and forced farmers who used GM varieties to purchase seed each year.

“Order 81 was not a law adopted by a sovereign country. This law was not enacted out of distress over the nourishment of Iraq’s people. The law’s lone purpose was to open a new potentially lucrative seed market for the multinationals that already controlled seed trade in other parts of the world.”[26]

There were millions of acres of wheat under cultivation when the U.S. invaded Iraq. Almost all of it was produced from seeds saved by Iraqi farmers or their regional suppliers. The strains of wheat being grown had adapted over time to the region’s climate.

The order stipulated that farmers were prohibited from reusing seeds of protected varieties, which would seem to indicate only the GM seeds being introduced. That is, until genetic drift occurs and all seeds carry a GM fingerprint. Wheat, despite any lab manipulation, is still an openly pollinating plant. Cross-contamination of traditional crops with GM crops is an old and common problem. Add to this the fact that Iraqi farmers had already been subjected to GM crops, prior to the war, going back as far as 1991.[27]

To help facilitate Order 81, the U.S. Army commissioned soldiers to hand out free wheat and barley seed, fertilizer, and even T-shirts, under the program known as Operation Amber Waves. It’s Japan 1853 again, only more insidious.

Iraq has an enormously rich agricultural history, reaching back to the beginning of agriculture itself. Farmers have been saving seeds for eons, and in modern times they were collected in a seed bank in Abu Ghraib. During the Iraqi war, the seed bank was destroyed. However, prescient curators of the seed bank had earlier sent a fabled ‘black box’ of seeds for safe keeping in Aleppo, Syria–hardly a stronghold of peace.[28]

With the co-optation of seeds as items of commerce, and by extension tools of imperialism, what are we, the people, the foodies, the gardeners, the peaceful, to do?

As contrary as it might sound, we must maintain hope. Kloppenburg’s analysis indicates that agricultural biotechnology is not yet paying off in the way that it was originally hoped. Life is far more complicated than they had anticipated. Yet their need to satisfy their investors hasn’t waned. The GM seed giants, in contrast to their swagger, seem to be running scared.[29]

“We do not have the luxury of doing this the right way. We are going to do this the way that gets it done the quickest, because our entire future depends on the success of this program,” stated Monsanto executives.[30]

They are running from a number of things. Testing of their products, for example, which they have routinely resisted.[31] The growing cry of environmentalists is mounting, and this adds to their fears. The highly publicized suicides of GM-adopting farmers in India has shined a very dark light on the GM industry in general. Historians, culturists, and other humanitarians are providing resistance. The social clamor will, I hope, bring down the seed giants eventually.

We can’t count on that, however. So we must be active on behalf of the underground. We must garden. We must save seeds or support those who do. We must re-establish our relationships with food-growers. We must take ourselves out of the commodity cul-de-sac and focus on progressive forms of commerce and sustenance. We must lose our inherited short-sightedness and develop long-term vision which will not allow life to become completely commoditized. We must be un-American.

We must advocate for peace and food sovereignty. We must be humble yet powerful, just like the seed.

Our goal is to preserve life so that it will flourish after the collapse. I realize that that sounds marginally kooky. But it is the truth, and we know it. We are collecting the artifacts out of which we will build the next world.

We see it happening all around us, with the rise of urban farming, hipster homesteading, rooftop gardens, an explosion of food writers. Social momentum is building, and change will come as a result. We will subversively dig our gardens, and in doing so, undermine the corporate hold.

“I want to tell you about the most hopeful thing in the world,” says Janisse Ray. “It is a seed. In the era of dying, it is all life. Every piece of information necessary to that plant for its natural time on earth is encoded, even though the world is changing and new information will be needed. But we don’t know what is in a seed; its knowledge is invisible, encased, secret. A seed can contain any number of surprises. A seed can contain a whole tree in its sealed vault. Even with climate change there will be seeds that have all the wisdom they and we need.”[32]

We must trust in all those secrets. They got us this far, after all.

As I write for this month’s Peace Meal Supper Club™ #10: Seed, I am looking at my seed flats, erupting with varieties of tomato, legume, chile, squash and other cultivars saved by my friends, seed saver networks, and my partner and me. I envision their placement in the raised beds I have built behind the house, on the bluff overlooking Seneca Lake. My daydream is pierced by the lunch bell: every day at noon, the Cargill plant in town sounds its air horn, signaling the start of lunch for the crew. It noisily insinuates itself into village life four times a day, and Cargill’s products have silently invaded Americans’ every meal. But my garden and I lie close to the earth and do our work, under the corporate clarion call. We perpetuate life, even though trouble is temporarily in the air.

——

The Menu

The menu highlights foods which are at risk in our present system, including apples, sunflowers, corn, peppers, various legumes and pulses, grains, fruits, nuts, and even maple syrup. It’s a delicious menu worth fighting for.

Course 1:

Apple & Fennel Salad ~ Sunflower Seed Cheese ~ Pomegranate Vinaigrette

Course 2:

Iroquois White Corn Timbales ~ Black-Eye Relish ~ Tabasco Aioli

Course 3:

Heirloom Paella en Croute

Course 4:

Mission Fig Crumble ~ Hickory & Pecan Clusters ~ Maple Cream

——

Further Reading:

The Seed Underground: A Growing Revolution to Save Food, Janisse Ray (Chelsea Green, 2012)

First the Seed: The Political Economy of Plant Biotechnology, 2nd Edition, Jack Ralph Kloppenburg, Jr. (University of Wisconsin Press, 2004)

Websites:

Seed Savers Exchange

Organic Seed Alliance

Via Campesina International Peasant Movement

GRAIN – International non-profit focused on food sovereignty

Organic Consumers Association

A host of articles regarding our agricultural invasion of Iraq:

http://www.mindfully.org/Farm/2004/Iraq-Plant-Variety-Law26apr04.htm

http://www.grain.org/article/entries/150-iraq-s-new-patent-law-a-declaration-of-war-against-farmers

http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v435/n7042/full/435537b.html

http://tribune.com.pk/story/342986/control-by-seed/

http://www.currentconcerns.ch/archive/2005/05/20050507.php

[1] Janisse Ray, The Seed Underground: A Growing Revolution to Save Food (Chelsea Green, 2012), 8.

[2] Jack Ralph Kloppenburg, Jr., First the Seed: The Political Economy of Plant Biotechnology, 2nd Edition (University of Wisconsin Press, 2004), 10, 29.

[3] Kloppenburg, 38.

[4] Karl Marx, Communist Manifesto, Chapter 1. Accessed online April 27, 2015. https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1848/communist-manifesto/ch01.htm

[5] Kloppenburg, 46. The centers of origin are also known as Vavilov Centers of Diversity, having been originally identified by Russian geneticist Nikolai Ivanovich Vavilov. See http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Center_of_origin

[6] Kloppenburg, 55.

[7] Kloppenburg, 56.

[8] Kloppenburg, 49.

[9] Edward M. East and Donald F. Jones, Inbreeding and Outbreeding: Their Genetic and Sociological Significance (Lippincott Co., 1919), 224.

[10] Kloppenburg, 11.

[11] Kloppenburg, 263; also see http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Plant_Variety_Protection_Act_of_1970#Contrasting_plant_variety_certificates.2C_plant_patents.2C_and_utility_patents

[12] Ray, 8.

[13] Chris Arsenault, “Small farmers hold the key to seed diversity: researchers,” Reuters, February 16, 2015, accessed April 27, 2015, http://www.reuters.com/article/2015/02/16/us-food-aid-climate-idUSKBN0LK1PO20150216.

[14] Kloppenburg, 76.

[15] Kloppenburg, 136.

[16] Kloppenburg, 6.

[17] Kloppenburg, 7.

[18] Ian Johnson, “China’s Great Uprooting: Moving 250 Million Into Cities,” New York Times, June 15, 2013, accessed April 27, 2015, http://www.nytimes.com/2013/06/16/world/asia/chinas-great-uprooting-moving-250-million-into-cities.html?pagewanted=all&_r=0.

[19] Charles Benbrook, Ph.D., “Impacts of Genetically Engineered Crops on Pesticide Use in the United States: The First Thirteen Years,” The Organic Center, 2009. Accessed April 27, 2015, http://bit.ly/1IhtK20.

[20] Kloppenburg, 158.

[21] Kloppenburg, 162.

[22] Kloppenburg, 161.

[23] Kloppenburg, 153.

[24] Kloppenburg, 172.

[25] Kloppenburg, 49.

[26] Ray, 33-34.

[27] F. William Engdahl, “Iraq and Washington’s Seeds of Democracy,” Current Concerns, March 7, 2005, accessed April 28, 2015, http://www.currentconcerns.ch/archive/2005/05/20050507.php.

[28] “Seeds in threatened soil,” Nature, June 2, 2005, accessed April 28, 2015, doi:10.1038/435537b

[29] Kloppenburg, 299.

[30] Kloppenburg, 300.

[31] Kloppenburg reports about their pressure to get the FDA to drop required nutritional testing, page 127. Also, the patent procedure typically requires some type of quality test of the product for which a patent is sought. This has not been required of seeds, whether GM, hybrid, or other derivation. Kloppenburg, 139. To make matters more unbelievable, university research conducted with or on GM seeds has been withheld from the public due to the information being deemed proprietary. Kloppenburg, 232. And finally, many licensing agreements specifically forbid testing for quality characteristics. See also http://www.scientificamerican.com/article/do-seed-companies-control-gm-crop-research/

[32] Ray, xiv.