I’ve written enough essays for Peace Meal Supper Club™ that I know when to turn the mic over to the experts. This month’s theme of Fair–as in Fair Trade–quickly became a maze of acronyms, political initiatives and their undermining, international trade agreements and their undoing, wonky treaties, and government actions against humans. Dissension among the ranks of Fair Traders further complicate matters. It simply is too much to encapsulate, even by my wordy standards.

The best I can do is to direct the reader’s attention to the work of others.

Fair Trade, as a movement, has its origins in a couple of places: post-World War II Europe and late 20th century Latin America. In the former, impoverished war refugees banded together in cooperative efforts to sell their crafts. Eventually, religious organizations such as the Mennonites and the Church of the Brethren helped establish fair trade supply chains into the developed nations. Ten Thousand Villages is the offspring of the Mennonite efforts. The Brethren, through their SERRV organization, became co-founders of the World Fair Trade Organization.

As for Latin America, after 19th century colonial land grants had marginalized the peasantry, multiple agrarian movements rose and fell, finally coalescing through the help of European alternative trading organizations in the 1970s. US organizations such as Equal Exchange joined the fight in the 1980s.

Of course the concept is much older. The Free Produce Movement, begun by American Quakers in the 1790s, focused on boycotting food and other goods produced by slaves, and encouraged the purchase of items made only by appropriately-compensated labor. Adam Smith, the cornerstone of modern economics, understood this, too: “Every business transaction,” he stated in The Theory of Moral Sentiments, “is a challenge to see that both parties come out fairly.”

The exact identity of the “parties” involved is subject to many interpretations. We’ll confine ourselves to two chief options.

Option 1: The negotiating parties are national governments, who may sign tariff treaties or formulate multinational organizations in order to produce favorable results for national economies. The North American Free Trade Agreement was an artifact of these efforts. The pending Trans Pacific Partnership is another. GATT (the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade) was an international treaty active from 1948 until 1995, when it morphed into the World Trade Organization (WTO). In general, these parties are in pursuit of Free Trade across political boundaries.

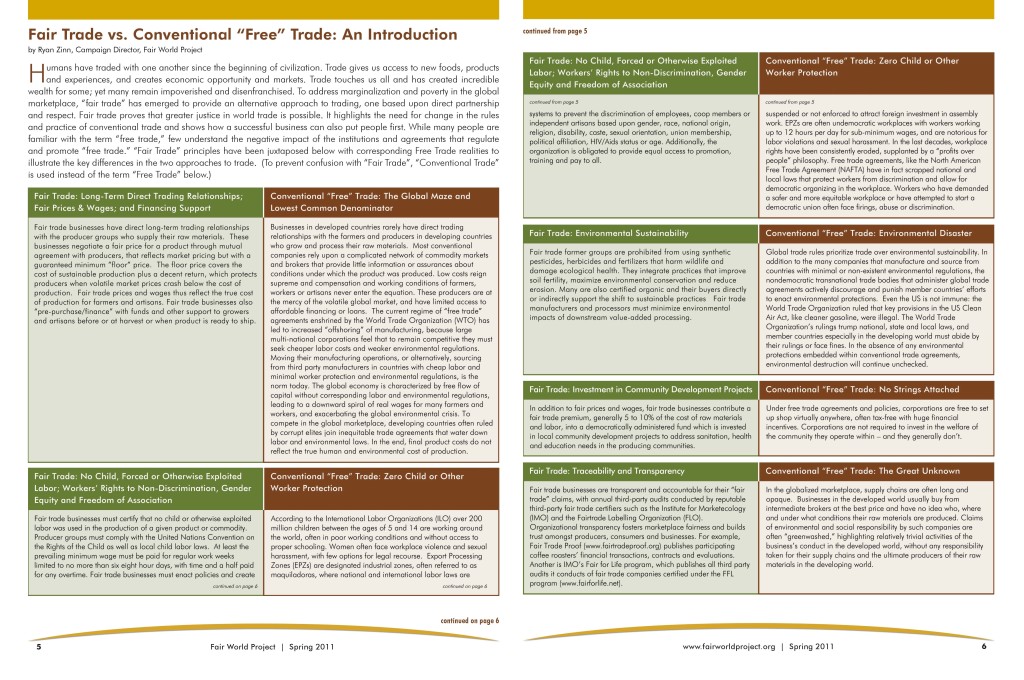

Books and websites abound to dissect and analyze the pros and cons of these various government-led initiatives. But the overwhelming effect is that small producers are left in the cold. The benefits accrue at a national levels and frequently at corporate levels, but do not translate into better livelihoods for the people involved at the ground level.

The WTO presents an interesting picture. It is a rules-based organization wherein the rules are not well-defined. Documents that exceed 30,000 pages, agreements made in Green Rooms comprised of privately invited guests, a problem-solving model that rests upon Negative Consensus, a Grand Bargain that hobbles developing nations–these do not make for fairly negotiated terms. Throw in some obfuscating taxonomy–Single Undertaking, Most Favored Nation, General Agreement, Aggregate Measures of Support–and you have created a barely navigable maze. The WTO functions in spite of itself, and to the advantage of developed economies.

But benefits accrued by economies do not translate proportionately into benefits for people in those economies.

Option 2: The parties are the people actually producing the goods, who act upon their own agency in matters of exchange. They live in culturally-rich regions, just like our own neighborhoods, and they want to preserve their ways of life and educate their children and have access to health care. (Psst…it’s what we’d want for ourselves…) Acting upon their own accord, they can secure these things for themselves. This is at the core of Fair Trade. It enables people to provide for their own needs, rather than proscribing them to foreign political agendas. It is a shift from extractive trade relationships to a fully supportive ones.

In the words of Fair Trade cooperative Equal Exchange:

“We believe the most promising hope for the future of small farmers, rural communities, sustainable eco-systems, and a healthy food system is to support small farmer organizations, educated and engaged consumers, and democratic social movements. By bringing producers and consumers closer together through greater mutual understanding and appreciation, and concretizing that through action, we can build and strengthen co-operative supply chains and a food system that serve the needs of ‘people not profit.’”

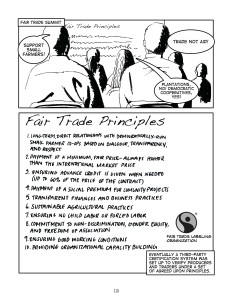

Serving the needs of the people across all industries and cultures is not a simple task, but is certainly approachable. Key principles, shared among multiple Fair Trade organizations, help solidify the numerous efforts. These principles generally include:

- Long-Term Direct Trading Relationships

- Payment of Fair Prices and Wages

- No Child, Forced or Otherwise Exploited Labor

- Workplace Non-Discrimination, Gender Equity and Freedom of Association

- Democratic & Transparent Organizations

- Safe Working Conditions & Reasonable Work Hours

- Investment in Community Development Projects, Pensions, Scholarships

- Environmental Sustainability

- Traceability and Transparency

Fair Trade is about structural change, from a philosophy of selfishness to one of equal reward. It’s about knowledge sharing, not sequestering, so that all fields may flourish. It’s about recognizing that the welfare of others is as important as our own–and indeed may eventually be our own. It even leads to changes in leadership, as cooperatives are able to establish themselves in the marketplace and then in political arenas. It is the headwaters of a sea change.

But of course, there are struggles–some in the form of corporate co-optation of the Fair Trade label, and with governmental favor still being granted to industrial-scale concerns. But the convergence of so many efforts–Fair Trade, organic, “locavore,” small producers, cooperatives, and human rights–provides a favorable climate of change.

To help you become more in-the-know, I recommend the following:

- Robert Reich’s 2-minute video on the Trans Pacific Partnership

- Oxford University Press’ Very Short Introduction: The World Trade Organization

- Oxford University Press’ Very Short Introduction: Globalization

- One-page comparison of Free Trade vs. Fair Trade (pdf) from Fair Trade Resource Network

- Concise answer to the question, “What is Fair Trade?” (pdf) from Fair Trade Resource Network

- “History of Fair Trade” (pdf) in comic book form, from Equal Exchange

- “Just Economy Interactive Tool” from the Fair World Project

- The “Small Farmers Big Change” blog.

- Product Guide from the Fair World Project

Many more resources are available through these websites:

- Equal Exchange

- Fair World Project (I highly recommend subscribing to their free bi-annual For a Better World publication.)

- Food Empowerment Project