Peace Meal Supper Club™ #12: Juneteenth is a celebration of common ground and progressive hopes. The menu highlights foods that are loved across all classes in the South, and have been for generations. They are not unique to any one group but represent a vast common foundational heritage, upon which we should be building a unified society.

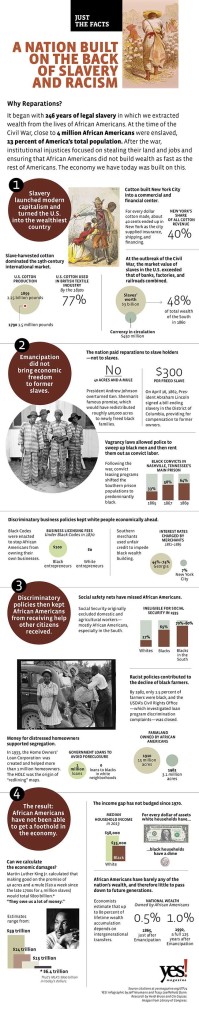

It is a challenging topic this year: as racial violence foments to a fever, we must face the incomplete and duplicitous work of our predecessors. Proclaiming freedom for all while utilizing captive labor, as did Jefferson, is hypocrisy. Proclaiming those captives free in a limited fashion, as did Lincoln, is also hypocrisy. Freeing those captives then doling out small tokens of fairness only when things begin to look a bit grim is likewise hypocrisy. Like other efforts that have sought equality–women’s suffrage and the ‘right’ to manage their own reproductive systems, for example–the movement towards full enfranchisement of non-male, non-heterosexual, non-white humans has been beaten back continually. Grudgingly, turf is yielded by the aggressors. Surrendered ground is reclaimed through acts of terror, such as the Emanuel AME Church shooting in Charleston last week. The terrorist has been apprehended, but sacred space has been violated once again.

As the Confederate flag flies full mast over South Carolina’s Capitol grounds–the US and SC flags are at half mast–Governor Nikki Haley declares that “we’ll never understand what motivates anyone to enter one of our places of worship and take the life of another.” Actually, Governor, racism is the motivation. President Obama laments the fact that a young man had possession of a handgun. (Check your Constitution, Mr. President.) But race-based crimes require no handgun. Hate will use any object it finds handy: a torch, a rope, or a pickup truck.

The Civil Rights Act of 1871 successfully led to the dismantlement of the Ku Klux Klan, but there was enough racist energy left to resurrect the hate group and its affiliates multiple times in the 1900s. Multiple Civil Rights Acts have been passed at the Federal level only to be challenged by various states, the President, or the US Supreme Court. Although all black males have been guaranteed the right to vote since 1870, the 21st century still sees virulent efforts to exclude black voters. These are not incidents in isolation, for bias runs as deep as bedrock, even at the Federal level. In 1999, a class action lawsuit was successfully executed against the USDA for its decades-long denial of loans to black farmers. And though slavery was outlawed in the United States by the 13th Amendment in 1865, we still possess an impetus towards involuntary servitude, particularly in agriculture.

~

I am a child of post-white-flight suburbia. I grew up in a Confederate state, institutionally shielded from even the mention of Civil Rights. I didn’t know Jim Crow from John Brown. It has stuck in my craw for a long time: the biggest social movement of the 1900s occurred during my lifetime, yet I discovered it in fragmentary fashion. Mythic rebel pride filtered every bit of learning. Cultural inertia was inclined toward Confederate sympathy. Disturbingly, that momentum still exists, even in surprising places: a few blocks from my home in Watkins Glen, NY, there is a Confederate flag posted above a neighbor’s doorway.

I do not view my culture of origin with disdain. My family is profoundly less racist now than it was two or three generations ago. The company I keep these days is generally progressive. But the fact remains that we–speaking of white do-gooders–benefit from what our forebears gained through forced labor. And all Americans, whether we are descendants of slaves or of freedmen, are still reeling from the trauma of our shared violent past. We live under the inertia of previous generations, and though it is residual, it is still powerful and leaves an indelible imprint. It expresses itself in fits of violence, righteous reactions, subversive terrorism, random eruptions, and institutional passive aggression. Institutionally–I am speaking of the government and its agencies and our capitalistic system–we have been socialized to act as though whites are important, non-whites are clearly secondary. When we excuse Jefferson’s holding of slaves, or Lincoln’s political maneuvering via the Emancipation Proclamation, we are reinforcing the institutionally racist culture we inhabit today.

So to have a meal to celebrate the emancipation of American slaves is indeed a delicate matter. Apart from the risk of misappropriation of a holy day, there is the chance that it can come off as self-congratulatory towards all of us social progressives who truly believe we are changing the world. Those of us who have never been oppressed walk a tightrope of social tension whenever we speak of liberty, equality, and brotherhood.

I really, truly, sincerely want the world to work in united fashion along progressive lines. But I have inherited the ability to want whatever I choose, and to get the majority of it. I am light years away from the reality of 40 million Americans.

~

During the Civil War, my birth state of Texas was relatively battle free. This, along with its position on the far western end of the Confederacy, prompted many Southern slaveholders to emigrate there.

“The idea was [that] Texas was so vast that the federal government would never be able to conquer it all,” says Jackie Jones, a history professor at the University of Texas at Austin. “There is this view that if they want to hold onto their slaves, the best thing to do is get out of the South and go to Texas.” Being on the fringes of the both the Union and the Confederacy gave Texans an excuse to ignore the Emancipation Proclamation and the surrender of Robert E. Lee at Appomattox.

The slave population in the state had risen to about 250,000 by the time Major General Gordon Granger of the Union Army landed in Galveston with an important announcement. On June 19, 1865, he stood on the balcony of the erstwhile Confederate Headquarters and read aloud General Order #3:

“The people of Texas are informed that, in accordance with a proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves are free. This involves an absolute equality of personal rights and rights of property between former masters and slaves, and the connection heretofore existing between them becomes that between employer and hired labor. The freedmen are advised to remain quietly at their present homes and work for wages. They are informed that they will not be allowed to collect at military posts and that they will not be supported in idleness either there or elsewhere.”

The Executive he mentioned was already dead and buried. The proclamation was already two and half years old. And oh, yeah: the South had surrendered a couple of months earlier.

The newly freed people rejoiced in the streets, exhilarating in the unimaginable. The following year, many of them reconvened on June 19th to commemorate the day they learned of their freedom. It naturally became a regular annual celebration.

Finding themselves prohibited from using public parks for Juneteenth celebrations, many of the former slaves pooled their funds and bought parks for themselves, such as the Emancipation Park in Austin, another Emancipation Park in Houston, and Booker T. Washington Park in Mexia, Texas.

The multiple waves of the African American Great Migration

brought the observance into other regions, and celebrations flourished in Oakland, Los Angeles, Seattle, and other major cities. Juneteenth suffered during the early 1900s, with the birth of Jim Crow and the resurgence of the Ku Klux Klan, then became a rallying date again during the Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and 60s. Today it is officially recognized in 42 states, including Texas. To its credit, Texas was the first to make it a state holiday. This happened in 1979, six years after Confederate Heroes Day was recognized as an official state holiday.

In this, the 150th year of Juneteenth, there is renewed interest in making it a Federal holiday. It will come with a bit of compromise: already Juneteenth has been poured into the standard American festival template of multiple stages, corporate sponsorship, lots of beer, and scores of food vendors. But commodification is not what the holiday is about.

Traditional Juneteenth celebrations emphasize education and achievement. The first observance in 1866 was used as an opportunity to educate the former slaves on how to vote. Honoring achievements at the community or national level serves as a gauge to measure the progress of the people. There is reflection upon the shared experiences of enslavement, displacement, abduction, and other trauma, but there is even more emphasis given to rejoicing in the victory of freedom. Self-improvement is encouraged, as is planning for the future of the family and the community. All of these components build resilience and vibrancy.

And of course, there is the food. The typical menu for Juneteenth is dazzling: barbecue and Creole dishes, cornbread, sweet potatoes, collards and other greens, black eyed peas, fragrantly seasoned rice, fruit cobblers, and red sodas.

Here’s an interesting thing about the foods associated with Juneteenth and the African American experience: I was raised on them, too, in my white-flight suburban home. These foods are shared among multiple ethnic groups along the lower economic strata. I was raised distinctly working class white with a solid cracker heritage. I am only a generation removed from subsistence farming–but I have to acknowledge that my family’s ability to possess their own land was indeed a privilege.

For me, here is a chance to illuminate common ground, to speak of shared heritage and overlapping experiences which can draw in both sides. Food is a powerful binder: “There is salt between us,” says an old Arab proverb. Once you share that salt–that meal–you cannot be enemies. Common foods come from common grounds, wherein we can sow seeds of peace.

The Menu

Course 1 comprises Maple-Braised Sweet Potatoes, a Cornbread Waffle, and a bit of Slaw.

Sweet potatoes will grow anywhere and produce prolifically, even in depleted soils. They are highly nutritious and keep well–perfect traits for food among the poor. They are reminiscent of African yams, and were quickly adopted by the displaced peoples of multiple African nations.

Corn was a shared food between enslaved Africans and Native American peoples, and directs us to the Seminole culture of pre-US Florida, where escaped slaves found safe haven. Once the US had negotiated the transfer of Florida from Spain, this culture was all but exterminated. Seemingly worlds away, my family also had deep ties to corn: my father’s uncle grew vast acres of corn as an East Texas tenant farmer. I remember us harvesting it by the pickup load, with my Mom working nonstop through the weekend to preserve it.

Course 2 offers Red Rice, Black-Eyed Peas, and Chow Chow.

Red is a significant color in Juneteenth celebrations. Some credit this to the hibiscus tea that was popular among the enslaved people, which we will also be having with our meal. Others say red is symbolic of the blood shed during the African American experience. In this traditional rice dish, tomatoes are slowly simmered in rich soul food seasoning until they break down, brilliantly dyeing the rice as it cooks.

Black-eyed peas, originating in West Africa, are an ironic gift to white Southerners who consume them for luck on New Year’s Day. I was brought up on them; they were a mark of Confederate pride instilled in me since birth. Knowing more about them now–and having betrayed the racist culture in which I was raised–I gratefully celebrate their true origin and embrace their deep multi-cultural mystery.

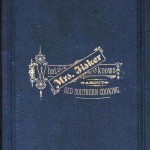

During the period of African enslavement, and extending into Juneteenth celebrations, black-eyed peas have traditionally been accompanied by a dollop of chow chow, a spicy sweet condiment made from green tomatoes, cabbage, and lots of vinegar. The chow chow I’ve made for Peace Meal Supper Club™ #12 was derived from my Mom’s recipe. It compares favorably to the recipe her grandmother used, which in turn is very much like that published by freedwoman Abby Fisher in 1881. Her book, “What Mrs. Fisher Knows About Old Southern Cooking,” was celebrated among the elite society of her adopted hometown, San Francisco.

Course 3 brings Tempeh Creole, Collard Greens, and Late Spring Turnips.

Creole means many things, and in this it reveals its chief characteristic: a mix of cultures. Creole cuisine descended from the fine skills of French chefs in colonial Louisiana. Based on a mirepoix derivative, utilizing New World ingredients, it forms the basis of New Orleans haute cuisine. As Americans moved into Louisiana and a territorial purchase was secured, Africans working in the kitchens further mixed the pot. Their influence on the fine cuisine of the South is incalculable. I am using one of their secret ingredients, sassafras, which they learned about through contact with Native American cultures. Sassafras, otherwise known as filé, provides both thickening for the sauce and an unmistakable Deep South flavor.

Collards are another poor man’s food, rich in nutrients, shared across every culture of the South–and many worldwide. Hearty, abundant, sustaining, and full of vitamin C, they are a powerhouse for the working class.

Course 4 is a burst of sweet tartness in the form of Blackberry Cobbler, served a la mode with Raspberry Sorbet.

During slavery and the early days of Emancipation, African Americans hadn’t much in the luxury foods department. But what they could forage, they could convert into a party. Wild berries provided a foundation for many of their pies.

Cobbler–a biscuit crust cooked over stewed fruit–was developed by the British American colonists, who found themselves without the proper ingredients or equipment for making steamed puddings. As the technique is simple, the ingredients common, and the equipment basic, cobbler was quickly adopted by those held as slaves. Cobblers have become strongly identified with Southern culture across all boundaries.

Juneteenth is a celebration of heritage and progress. In that spirit, I am proud to be serving this menu on my Mom’s china. She purchased it one piece at a time through a locally-based supermarket during the 1970s. Arrangements like this were common–such as towels being included in boxes of laundry detergent–and enabled the lower classes to acquire the trappings of the upper classes.

It is a wonderful inversion of class, which is also an important if unspoken element of Juneteenth. As related on juneteenth.com: “During slavery there were laws on the books in many areas that prohibited or limited the dressing of the enslaved. During the initial days of the emancipation celebrations, there are accounts of former slaves tossing their ragged garments into the creeks and rivers to adorn clothing taken from the plantations belonging to their former ‘masters’.”

“By putting on their very best clothes, the black people were signaling they were free,” history professor Jackie Jones relates. “It enraged white people. They hated to see black people dressed up because it turned their world upside down.”

~

Peace Meal Supper Club™ has always been both celebratory and sobering. The menus have undoubtedly been about enjoyment and indulgence. The themes have always been about knowing more and vowing to do more. Being gently demanding and straightforward, PMSC™ always reinforces a generally gritty message: we have a lot of work to do. We must constantly work to reconcile the impact that our privileged lives have on the world around us. Our privilege came with a price which we did not pay.

The truth of the matter is that change is occurring. As African Americans have progressed, so has American culture. Change has come through careful negotiations, violent upheavals, broken promises, public demonstrations and silent vigils. While we are frustrated and angered with the backward steps–and plunges into white supremacy darkness–we stand in a much more unified and progressive world than that of June 19, 1865.

With Peace Meal Supper Club™ #12: Juneteenth, I do not intend to imitate or co-opt. I have learned so much from the complexity of our contradictory American heritage, as painful as it has been for many to endure. I gain from learning of the indomitable spirit that is central to Juneteenth. Therein lies perseverance and determination that I will never know. I am thankful for the spirit of Juneteenth, and celebrate our common human ground.

“Strengthening the ties that bind us should always be our objective. Unity and peace are our goals,” states a press release from a leading Juneteenth organizer. May that spirit be ours, eternally.