Next to water, tea is the most consumed beverage in the world. It did not flow around the world naturally or easily, even though it is an icon of peaceful mindfulness.

Tea’s character is one of communion, meditation, hospitality, and universality. From the bustling cosmopolitan US south, where it is served over ice with cane sugar and a hint of lemon, to Kyoto where it is whipped into a heady froth in an austere, neo-religious ceremony; from treat-laden afternoon tea at Harrod’s in London, to a never-will-I-find-this-again chai bodega on a jungle road outside of Hyderabad, we are all drinking of the same tree. Japanese cultural historian and preservationist Okakura Kakuzo spoke of tea as the “cup of humanity.”

Camellia sinensis originated in southwestern China, in a region now divided among the provinces of Sichuan and Yunnan, and the country of Burma. Legend has it that Shennong—sage, farmer, inventor, king, health advocate—was meditating as his attendant boiled water for him to drink. Leaves from a nearby tree drifted into the pot, and Shennong loved the color the leaves imparted. He chose to leave them in. The resulting beverage delighted him to no end, and he urged everyone to try it. “Tea gives vigor to the body, contentment to the mind, and determination of purpose,” he later wrote. This was around 2500 BCE.

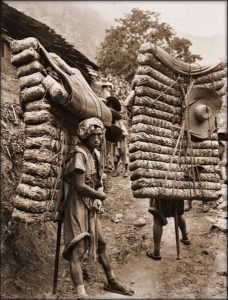

His idea caught on, and tea culture began growing throughout China. During the Song Dynasty, 960 CE to 1279 CE, tea crossed into Tibet, a region too cold for tea cultivation. The Chinese transported tea by foot, hundreds of pounds per man, along a network of roads stretching through Yunnan, Sichuan, Burma, Tibet, and Central China. This collection of roads became known as the Tea Horse Road, one of the earliest international trading networks, similar in scope and importance to the Silk Road, the Grand Trunk Road, and the Inca Road System.

The two main commodities exchanged over the Tea Horse Road were Chinese tea—the earthy and durable pu’ehr—and Tibetan horses—war horses to be exact. This goods-for-arms exchange allowed the Song emperors to combat nomads as their empire spread northward. This was not the first time commerce was used to finance war—nor will it be the last.

Tea’s growth from local health beverage to international commodity was paralleled by its codification as a ritual drink. Lu Yu, revered in tea culture as the first Tea Master, produced the landmark Classic of Tea in the 8th century CE. In it, he gave obsessive directions for water temperature, steeping methods, equipage, along with concise bits of philosophy. He wrote disdainfully about people who “boil tea with green onions, ginger, dates, orange peels, dogwood, and mint. Then, they either keep scooping and pouring the tea back into the pot to mix it as it boils, so that it tastes smoother and does not foam, or they simply scrape off the dregs and foam. This kind of tea is not unlike the swill of drains and ditches, and yet, alas, many people are accustomed to drinking it!” He did, however, approve of adding salt.

Our First Course—Pu’ehr and Shiitake Waffle, Adzuki Ragout, Ginger Plum Sauce—honors him obliquely and ironically.

This irony is not without purpose. When speaking of imperialists and indigenous nomads, we must always consider who are the invaders. We must do the same when examining orthodoxy versus free thought. Which will carry us forward into a brighter, more peaceful and progressive future? The state, with its mandates of compliance, canonists who condemn experimentation, or the bands of rebels who value liberty and new ideas?

Our second course provides insight to an answer, by echoing the spirit and esthetic of another important Chinese teacher, the possibly mythical Laotse. The attributed author of the Tao Te Ching, he presented the universe as flowing around obstacles, seeking the lowliest of places, pliable and adept at change. Everything changes, constantly, repetitiously, and the art of life is to adapt. Laotse’s teachings seemed at odds with his contemporaries, the Confucians, who venerated elders, adhered to customary rites, and supported established social orders. Their values, superficially at least, seem absolute. But with the Tao—and with tea—the absolute is relative. Everything changes, everything passes, everything is in a state of becoming—including us.

As Chinese emperors struggled to defend and extend their domains, the Tao—disguised as Zen—made its way into Japan. There, in the 9th century CE, it rendezvoused with its old familiar, tea. They formed an infinite mirror of clarity and simplicity, culminating in the ceremonial preparation and presentation of tea known as the Japanese tea ceremony. As with corresponding ceremonies in China, Vietnam, Korea, and other regions, the Japanese tea ceremony is about more than tea, encompassing floral arts, poetry, hospitality, and graceful austerity. It fills empty spaces with humbling simplicity, elevating the performance of service. It is an esthetic unto its own, promoting the concept of wabi sabi, or the acceptance of transience and imperfection. Wabi sabi, like the Tao, is a sense rather than a structure.

The tea consumed at the climax of the ceremony is matcha, a powdered green tea which is whisked vigorously until it begins to foam. Drinking this strong tea on an empty stomach can cause digestive discomfort, so the ceremony begins with a multi-course meal. The meal, called kaiseki, is a show of hospitality, skill, and good taste, each course illuminating the host’s character. Traditionally, the third course of this meal is a clear soup called wanmori. Often, this soup portrays a landscape or scene from nature, to encourage an appreciation of asymmetry and the beauty of imperfection.

Our Second Course—Sencha Broth with Steamed Sweet Potato, Carrot Flowers, and Nori Confetti—reaches from soil to stars, offering a portrait of the Tao in tea. As we all drink from the same tree, sharing in the cup of humanity, how do we balance progress with imperfection?

Especially when the imperfection weighs so heavily upon humanity. After engaging in vigorous commerce with China during the 17th and 18th centuries, Britain had accumulated substantial trade imbalance. They desired tea, silk, and porcelain wares from the Chinese, who in turn wanted nothing but silver. To get this silver, the British had to deal with the Spanish, who plundered silver from Andean mines. The global economy of the time—as in our time—was multi-national, extractive, and heavily integrated. Inequities were natural and expected. The British economy felt the pinch.

To resolve their trade imbalance, the British began growing opium in their recently-acquired Indian territories. This opium was then imported clandestinely into China, undermining not only Chinese prohibitions on opium but also the government’s sovereignty. The Chinese found themselves facing widespread addiction and bankruptcy, as silver clinked back into British coffers. Two trade wars followed—known as the Opium Wars (1840s and 1850s)—resulting in unequal treaties, in which China was forced to open its ports, territories, and population to British commerce and influence. As for the British, they ceded nothing. They gained Hong Kong, legalization of the opium trade, and Chinese sanction for human trafficking.

As these wars were raging in the foreground, the British were also working undercover. The Chinese government forbade the export of tea plants, and substantial penalties were exacted against anyone who aided a foreign party in obtaining tea plants or information regarding their propagation. Tea trees, their seeds, and the technology for their propagation were the property of the Chinese government.

The British East India Company, however, were not easily dissuaded. In a daring and damaging multi-year mission, Scottish botanist and plant hunter Robert Fortune travelled illegally throughout China on the Company’s behalf. By posing as a Chinese merchant—his Scottish accent notwithstanding—he procured plants and seeds, shipping them out through various covert means. By the end of his travels in 1851 he had stolen 20,00 tea plants, and was able to persuade a contingent of Chinese tea experts to immigrate to India, which was also forbidden by the Chinese government.

These efforts, coupled with the discovery of wild tea plants in northern India, led to the establishment of the tea industry in Assam, Darjeeling, and other British-controlled regions. In the years since, Assam tea has become a global standard, while Darjeeling tea, with its delicate bouquet and amber elegance has become regarded as the ‘champagne of teas,’ an elite and rare brew.

Tea is very sensitive to climate, and these two Indian teas have distinctly different characteristics. Assam is robust, malty, and resilient, while Darjeeling, grown in a wonderfully dense microclimate, is delicate to the point of vulnerability. Darjeeling tea, in fact, might not exist in another 50 years, a casualty of post-modern climate change. What will take its place? What was there before we introduced it?

Course Three—Five Spice Tofu, Forbidden Rice, Darjeeling Gravy, Orange Poppy Stir Fry—attempts to portray a sense of culture clash and turmoil, albeit on the delicious side. With its syncretic profile—Chinese seasonings, Indian tea, and global addictions—it portrays the current global landscape: unequal commerce; subversion of sovereignty; trafficking in drugs, humans, and agricultural products; war for the sake of economy; industrial monoculture; corporate imperialism; climate change; and fleeting elegance.

Is our life itself, much like Darjeeling tea, merely an effervescence?

The Indian state of Assam is the world’s largest tea-growing region, flourishing on the merits of its own varietal, camellia sinensis var. assamica. Woody, brisk, and full-bodied, this tea is one of the most widely-used teas globally. In 1824, this varietal was introduced into Sri Lanka, where it took over plantations which had formerly been dedicated to the likewise-introduced coffee (and cinnamon before that). The Assam varietal also spread through Indonesia, and has spawned a sub-varietal known as camellia sinensis var. cambodiensis, which occupies massive plantations throughout southeastern Asia. Many African and several Middle Eastern countries also produce tea from this stock.

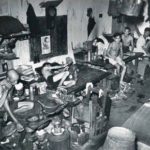

The cultivation and production of tea is labor intensive, relying on human hands for harvesting and intricate processing. As is the case with other major world commodities—coffee and cacao, to name two—those hands are often underpaid and at times belong to children. We, as beneficiaries of their labor, must consider their welfare in our consumption, just as we must reflect upon the impact we are having on their landscape, waterways, and social conditions. We are in direct communion with them, in every luxurious cup of chai, every refreshing glass of iced tea, and in the decadent final course for this meal.

Course Four presents another stylized portrait, one which is much darker thanks to two black teas, Assam and Earl Grey. In this intense dessert—Thai Tea Ice Cream Sandwich with Lemon Ginger Pastry Cream—we sense a sobering and far-reaching elaboration of the Tea Horse Road trade system. We are still exchanging goods, armaments, contraband, humans, and technology in a global network that is mystifyingly complex, unsustainable, and seemingly unchangeable. Our landscape and our humanity readily display the effects.

Course Four also posits a question: Amidst all the excess, have we lost our esthetic? If the object of our desire—in this case, tea—is so thoroughly obscured by accumulated addictions—sugar, wheat, milk (even the non-dairy varieties), and, frankly, luxury—then have we lost our litheness, our elegant ability to flow around obstacles rather than to be trapped by them? Has our clarity surrendered to the clouds?

Or from another angle, perhaps more apropos, we should ask: Has our sense of progress been dulled by our encountering too many obstacles? The institutions we face are monolithic, but even stone can be worn away by a persistent and purposeful stream of intention.

Peace Meal Supper Club™ #19: Camellia offers a reminder, an encouragement to refocus, a reification, if you will, of the spirit of tea as proposed by Okakura Kakuzo in The Book of Tea. That is, an “adoration of the beautiful among the sordid facts of everyday existence…a tender attempt to accomplish something possible in this impossible thing we know as life.”

Let’s refresh our cup of humanity and regain our clarity. We are making progress, but there’s still a lot of work to do.

Read More, Learn More

The East India Company: The original corporate raiders – A fascinating and maddening long read (courtesy of The Guardian) relating the corporate takeover of India by a single British company.

A timeline of tea history, presented by one of the busiest tea auction houses in the world, the Guwahati Tea Auction Centre (GTAC). There’s lots of other good info for those who are addicted to link-clicking!

A few books:

Darjeeling: The Colorful History and Precarious Fate of the World’s Greatest Tea, by Jeff Koehler

The Story of Tea: A Cultural History and Drinking Guide, by Mary Lou Heiss and Robert J. Heiss

Tea: A Global History, by Helen Saberi

The Harney & Sons Guide to Tea

And really, read this book: The Book of Tea, by Okakura Kakuzo