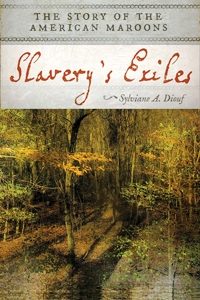

Peace Meal Supper Club™ #20: Maroon visits communities that most of us never knew existed. For over 200 years, men, women, and children escaped American slavery and established alternative societies in the Southern wilderness. Known as maroons, these resilient and creative individuals were feared and celebrated from the early 17th century to well after the Civil War—even if public acknowledgement of their existence was withheld. Together, they redefined their lives, defied the system which brought them to America, and built a culture of freedom and self-determination along the borders of American plantation society.

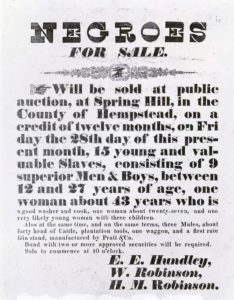

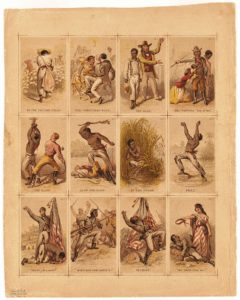

Their commitment to personal freedom—to not be subject to white control—required fearlessness, resourcefulness, and the ability to navigate unknown geographies and languages. After being abducted in their homeland, held in barracoons for weeks or months, stacked in ships to make the Middle Passage, all the while subject to whipping, branding, shackling, starvation, brutality and humiliation, their resolve to control their own persons overshadowed any fear.

Some escaped on the day they were unloaded at the dock. Others fled after laboring for years. Leaving a plantation was no light undertaking, and was often prompted by the sale of a family member, a severe punishment, having reached one’s limit, or having completed years of preparation. The inhumanity of slavery was so intense that it was better, in the opinion of the maroons, to take one’s chances in the wilderness with its unknown terrain, flora, and fauna.

Their existence is a powerful rebuke of forced labor and the American slavery system. Or as anthropologist Dan Sayers says, “These people performed a critique of a brutal capitalistic enslavement system, and they rejected it completely. They risked everything to live in a more just and equitable way, and they were successful for ten generations.”[1]

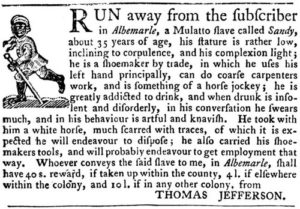

A few key characteristics set maroons apart from “runaways.”[2] “Runaways” often had one of two goals in mind: temporary relief from harsh treatment, after which they would return to the plantation; or finding their way to a non-slave territory in the North. In either case, “runaway” usually indicates a temporary condition.

A maroon, on the other hand, was pursuing permanent freedom from a slaveholder while remaining in slave territory. It’s a startling pursuit—to be free but live among the enemy. Successful maroon colonies existed in Suriname, Brazil, and other regions of the Americas. Some were strong enough to go to war with their oppressors and win. But in the American south, they were a scattered population with a tenuous grip on freedom.

(Marion Blackburn)

There are no exact figures on American marronage, just as there are none for “runaways,” successful Underground Railroad passengers, or the enslaved population as a whole. A chief characteristic of a maroon was his or her ability to stay undetected, so an accurate figure is unlikely. Sayers, who conducts archaeological excavations within the Great Dismal Swamp estimates the population there to have fluctuated between 30 to 40 individuals at a time, over a span of 250 years. There were significant settlements in the Carolinas and in Louisiana, while thousands of individuals were going it alone throughout the South.

As for why a person chose marronage over the Underground Railroad or flight into Spanish Florida, the primary reason, according to historian Sylvanie A. Diouf, appears to be family.[3] They desired close, if intermittent and risky, contact with a spouse or child or parent. For displaced Africans, “to have been uprooted and separated from family was an immense, unfathomable loss; it tore apart the very core of their self-identification as human beings, because to be human was first and foremost to be part of the social fabric.”[4]

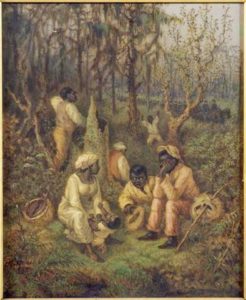

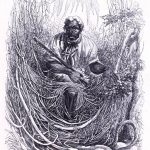

The maroon’s life was one of shadows. They hid in plain sight, often just outside the plantation’s border. Some built platforms in dense trees, others found shelter in caverns, and many dug habitations underground—an enterprise that often took days, and had to be done without anyone noticing that the ground had been disturbed. They screened their shelters—be they cave, cavern, or tree—so skillfully that most went undetected for years, even those within plantation boundaries.

Living on or near the plantation grounds offered more frequent interaction with family, but came with enormous risk. For greater security and increased freedom, some maroons ventured into the hinterlands. They built homes in the wilderness between plantations, in thickets, swamps, or mountainous regions that didn’t yield easily to agriculture. A few remote settlements held a dozen to fifty inhabitants, their populations fluctuating as hunts, abductions, and accidental discovery happened all around them.

Interviews of over 2000 formerly enslaved men and women conducted by the Works Progress Administration in the 1930s provide windows into their lives: Maroons stayed underground during the daytime; visited family members at night; obtained sustenance from forest gardens, enslaved friends, the plantation kitchen or smokehouse; and established friendly relationships with the dogs who would be used to hunt them.

To maintain their freedom among incessant risk, maroons developed warning systems, obtained arms from complicit freedmen and whites, and formed communication networks which included enslaved blacks, supportive whites, sympathetic Native Americans, and marginalized laborers of every ethnicity. They were a society whose existence was founded on trust and loyalty—and there were many weak spots in this bulwark.

Along with communication networks, maroons established an extensive alternate economy. Goods flowed between plantations, woodlands, and city businesses, with maroons trading by night and even in open daylight. Diouf writes, “Instead of bartering in the woods or on plantation grounds furtively at night, some maroons traded openly in the cities. Seven men, four women, and five children, who escaped from Charleston and lived in the woods near The Oaks plantation—their former homeplace—were probably some of the most adept at doing business in an overt manner. ‘They are not only supported by the people of the adjoining plantations,’ complained their owners, who received reports of numerous sightings, ‘but pick black moss, make baskets, and take them to the City in boats through Wappoo Cut.’”[5] Making several trips into the city per day, they sold their goods to shopkeepers. This income allowed them to purchase food and other supplies to support their independence.

Along with communication networks, maroons established an extensive alternate economy. Goods flowed between plantations, woodlands, and city businesses, with maroons trading by night and even in open daylight. Diouf writes, “Instead of bartering in the woods or on plantation grounds furtively at night, some maroons traded openly in the cities. Seven men, four women, and five children, who escaped from Charleston and lived in the woods near The Oaks plantation—their former homeplace—were probably some of the most adept at doing business in an overt manner. ‘They are not only supported by the people of the adjoining plantations,’ complained their owners, who received reports of numerous sightings, ‘but pick black moss, make baskets, and take them to the City in boats through Wappoo Cut.’”[5] Making several trips into the city per day, they sold their goods to shopkeepers. This income allowed them to purchase food and other supplies to support their independence.

The possibilities of licit income were few, but maroons exploited the channels that were open to them. Some gathered wood in the forests around New Orleans, then sold it to steamships as firewood. Others traded with poor whites, bringing them foraged berries or plantation corn in exchange for fabric or clothing.[6] Still others hired themselves out to dig canals or to fell forests.

“Maroons were a cheap source of labor,” writes Diouf, “and their illegal status made them vulnerable and thus unlikely to complain; but by engaging in illicit dealings the employers also exposed themselves to opprobrium and reprisals if discovered. The deal between both parties rested on the most improbable trust…The arrangement, mutually beneficial, is an apt illustration of the maroons’ pragmatism, entrepreneurship, and self-confidence as they diversified their activities and widened their networks—in a potentially perilous manner—in order to preserve their independence.”[7]

In an ironic twist, some maroons hired themselves out to plantation owners, supplying cheap labor for lumber milling, shingle production, and dam building.[8] Plantation owners and urban businessmen alike bought fish and oysters from the best fishermen in South Carolina—the maroons.[9]

Some maroons thrived in this underground lifestyle and shadow economy. Others, however, suffered their way through it, never able to get enough food or goods to make their lives sustainable. Subject to exposure, hunger, malnutrition, lack of sunlight, and injury without medical attention, many returned to plantation life. But there were also many who chose slow death over resubmitting to white control.

For the maroons who returned to plantation life, the punishments could be severe. Accounts tell of people receiving hundreds of lashes, leaving some on the brink of death. Branding on the face, cutting of the ears, castration, and severing the Achilles tendon were, at one time or another, legal punishments. Severe whippings were the most common, designed for not only pain but humiliation, breaking of one’s spirit, and terrorizing other would-be maroons. “Pickled whippings” were frequently administered: a woman or man would be whipped until their backs were stripped of skin, then doused in brine, red pepper, vinegar, or turpentine. At times, punishments were even more extreme.[10]

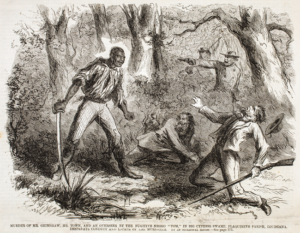

As maroons, people often found themselves hunted by planters, police, and hired professionals. Almost all hunts involved dogs. Advertisements, posted in papers and on city boards, gave detailed descriptions of a man or woman, requesting that any sighting be reported. Catawba trackers were often employed, as were citizen vigilantes. In a foreshadowing of the Labor Wars of the 1800s, state militia were often called out to help a plantation owner recover, dead or alive, his lost “property.”

While a majority of maroons were captured or returned voluntarily, the armed hunts were not always successful. Maroons’ very existence shamed planters, but their ability to evade capture made planters furious: it attacked the myth of white superiority. Diouf states, “They were a daily reminder that slavers could not exercise absolute control on either the people in the woods or those in bondage who aided and abetted them. Cunning and smart, one step ahead of the men and women who set the dogs after them, the maroons were Br’er Rabbit who outsmarted the strong and the powerful. Their feats ridiculed slaveholders…who had proved incapable of finding a man, a mother with children, or a family of ten living two miles from their own bedrooms. Even more, they fed them their hogs, their chickens, and their corn. And because it was largely based on the active help and silent support of the enslaved community, the maroons’ success, even when limited, was everyone’s accomplishment.”[11]

To stifle this empowering message, planters, magistrates, governors, and other influential whites relied on public propaganda designed to generate mass panic. Maroons were routinely characterized as violent insurrectionists who invaded farms and small towns, raped women, burned houses, killed indiscriminately, and plotted overthrow of the government. Perhaps their greatest crime, however, was that they no longer showed the submissiveness required of them. This act alone made them criminals as a class of people.

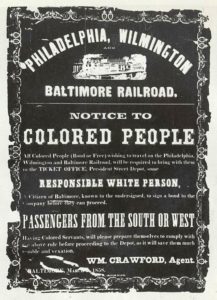

Along with the propaganda campaigns, Southern authorities banned radical literature from the North—such as David Walker’s 1829 Walker’s Appeal, in Four Articles, a landmark abolitionist document. Spies infiltrated the maroons’ communication networks, and all freed blacks were required to carry, at all times, documents attesting to their freedom. In the late 1840s, both enslaved and free laborers in the Dismal Swamp were registered in official logs, with their physical characteristics—age, complexion, height, unique features—described in detail. If found without their ID card, they were subject to fines, imprisonment, and whippings.[12]

It is not difficult to see the similarities to our own times, not only regarding public paranoia about immigrants and people of color. The United States has a centuries-long tradition of abusing its workers: Native American and African slaves, Chinese coolies,[13] miners and factory workers, braceros, the prison population, present-day H-2A card holders, and countless undocumented workers across the country. Industry and government have colluded against the workers through strike-breaking, union-busting, passing legislation with generous loopholes, and persistent refusal to raise the minimum wage. All the while, the workers are vilified as lazy, rebellious, ungrateful, rapists, murderers, gang leaders, insurrectionists, drug-dealers, and un-American.

The maroons—even the recaptured and surrendered—subverted the American model. Their existence not only condemned the institution of slavery, but questioned the morality of the political economy. A system that requires the sacrifice of workers—especially those who have been abducted—is a system that must be dismantled.

“Within the larger narrative of slave resistance, maroons offered a unique experiment. They created and exposed to whites and blacks an alternative to life in bondage, an alternative to free life in a slave society, and an alternative to free life in a free state. Whatever the immediate cause of their marronage, they opted to exile themselves from a despotic, discriminatory society. Their removal to the wilds was not only a denunciation of the social and political order of the land but more profoundly a radical ideological and very concrete rupture that left no place for compromise,” offers Sylvanie Diouf.[14]

Some maroons retained their freedom right until the end of the Civil War. They left their caves, trees, caverns, and other makeshift dwellings to walk freely in the countryside and towns. A few, such as those who lived in the Great Dismal Swamp, remained safely isolated, by choice, from white society. In their day the maroons inspired others, as plantation-bound slaves lived vicariously through them or followed them into the forests. Today, they still serve as inspiration. So what will we do?

There is much we can do, in solidarity with those who struggle in the American model. The most impactful economic action is to withdraw our support from oppressive systems. To do this, we must learn to grow, to sew, to cook, to simplify, to restore, to reuse, and to resist. Alternative economies will thrive with our participation, and for our involvement we will get a new window into the world.

As we are marooning the American system, we must fight for the rights of others. Immigrants, refugees, agricultural workers, indigenous peoples, and native cultures worldwide need champions—like you and me.

The menu for Peace Meal Supper Club™ #20: Maroon is drawn from their experiences, common foods, and interactions between them and civil society.

Course 1—Corn & Potato Chowder, Black Pepper Biscuit—uses common maroon foods to highlight the skill and resourcefulness marronage required. Diouf tells of how the maroons sustained themselves through acquiring goods from nearby plantations. Solo or in small bands, maroons would enter the plantation grounds, approach the various storehouses or even the kitchen, and take the things they needed. Through extreme risk, they were able to sustain themselves until they were able to grow their own foods and make their own clothes. Among the more common food items they procured from the plantations were corn and potatoes.

One significant haul related by Sylviane Diouf: “In Louisiana, three men got away with three shirts, two pairs of pants, one jacket, some money, a petticoat and a woman’s chemise, a sheet, a woolen blanket, three sacks, a bucket, a sifter, half a barrel of rice, a third of a barrel of salt, two pound of meat, some fresh cheese, and five barrels of corn.”

The Black Pepper Biscuits are also significant. To elude hunters with dogs—hunting for men—maroons would put black pepper in their socks. The pungency of the pepper caused the dogs to lose the trail. Bay leaves were also used for this purpose.

Course 2—Field Pea Fritters with Root Relish—is based directly on a preparation enjoyed by maroons. They would mash fresh field peas, form them into rounds, roll them in cornmeal, and fry them. By serving these with Root Relish, I’m including their practice of pickling and fermenting to preserve foods for the winter.

Course 3—Carolina Gold Rice Cakes en Feuille, Smoked Mushrooms, Sauce Filé—is inspired by the underground lives of the maroons. I mean this in a literal sense, as in the caves they built for themselves just outside plantation boundaries. Some dugouts were, in fact, on plantation grounds, yet men, women, and sometimes entire families lived in them without being detected. One key factor was to make the caves invisible, hiding the entrance so thoroughly and deftly that the ground did not appear to be disturbed in any way.

The caves were reinforced for durability, furnished at times, and filled with foods the inhabitants had acquired through their garden, plantation acquisitions, trade, or hunting. Rice was one of the staples of the underground pantry. Maroons were known to take it from plantations, grow it themselves when they had the opportunity, and purchase it with money they had earned. It was ubiquitous. Carolina Gold Rice is an heirloom variety, one of the first plantation rices to be grown in the American southeast—and therefore inextricably linked to slave history. It flourished under African care and skill, which led to expansion in plantation holdings and therefore the need for more manpower. It was a vicious cycle, but their fondness for this rice prompted many maroons to take it with them when they could.

I’ve wrapped the rice in cabbage leaves, which is a technique utilized by the maroons themselves. It’s an old tradition, much like wrapping tamales in corn husks or banana leaves. It’s a direct connection to Western African tradition, although in their homeland they used other leaves besides the Asian/European cabbage.

Finally, this course offers smoked mushrooms, as a nod to another maroon cooking and preservation method; and a sauce based on filé, or sassafras, which once flourished in the swamplands inhabited by maroons.

Course 4—Sweet Potato Quick Bread, Blackberry Jam, and Whisky Molasses Glaze—offers a decadent, grounded, and meaningful exchange. Flour, molasses, and whiskey were often traded or purchased by maroons through their alternative economies. Sweet potatoes were grown as sustenance foods for the winter. The blackberry jam I received from friends, which adds its own elegant relevance.

[1] Richard Grant, “Deep in the Swamps, Archaeologists Are Finding How Fugitive Slaves Kept Their Freedom,” Smithsonian Magazine, September 2016, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/deep-swamps-archaeologists-fugitive-slaves-kept-freedom-180960122/

[2] I use the term “runaway” in quotes to denote its inappropriateness despite its common use. Africans were kidnapped, held through violence, cut off from their native customs and language, taken to a foreign land with an incomprehensible tongue, and forced to submit to others. Leaving this situation hardly makes them runaways. The term has negative connotations, and their actions were anything but negative.

[3] Sylviane A. Diouf, Slavery’s Exiles: The Story of American Maroons, (New York University Press, 2014), 42.

[4] Diouf, 53.

[5] Diouf, 121.

[6] Diouf, 122.

[7] Diouf, 123.

[8] Diouf, 159, 214.

[9] Diouf, 150.

[10] Diouf, 298.

[11] Diouf, 303.

[12] Diouf, 214.

[13] I use this term in its original sense, that is, “laborer.” Like many legitimate terms, it fell into use as an insult, a pejorative which questioned someone’s moral and monetary worth. I use it as an acknowledgement of the strength and courage it takes to be a worker.

[14] Diouf, 309.