Utopia glimmers throughout the menu for this month’s Peace Meal Supper Club™, as we face the New Year with thoughts of a New World. What would we want it to look like? As we take mind excursions into perfect worlds, it helps to have a few ideas in our pockets. Having a good meal as we depart is nothing if not practical.

The menu comprises elements of Utopias past, reaching from Greece’s Golden Age through Eden’s Mesopotamian homelands, over the Himalayas into Shambhala, finally arriving in a mystical “no place” in China, where the Peach Blossom Spring flows eternally. It’s a journey of innocents abroad and innocence lost, leaving us wiser and more resilient for our disappointments.

As self-appointed chief cook and bottle-washer of the Peace Meal Supper Club™, one of my most enjoyable tasks is to pull together a harmonious cross-cultural menu, one which draws attention inward rather than scattering it hither and yon. Ancient cuisines provide ample room to play; they are supple in their simplicity, bending and blending gracefully as they support a progression of ideas.

For this month, I have an additional voice weaving the harmony: the network of trade routes known as the Silk Road. From its early beginnings in the 2nd millennium BCE, this conglomeration of routes eventually stretched from imperial Rome to Beijing, only falling into disuse in the mid-1400s. As an early expression of globalization, its avenues ring with ominous tones: dun dun duuunnn…

Though trouble might be over the next horizon, we can sample local flavors as we tramp along the Silk Road to perfection.

First stop: the shadow of Mt. Olympus, where the Golden Age of Greece began with the creation of humankind. There, as Hesiod tells us, women and men lived in joyful leisure, equally sharing the abundance that the earth provided them, in a state of innocence. Their paradise went up in smoke, however, when Prometheus gifted them with fire. Hell further engulfed them upon the subsequent opening of Pandora’s box.

Echoes of the Golden Age are found in Mesopotamia, in the Bibilical stories of Eden. The garden’s inhabitants were sinless, and through no labor of their own, enjoyed the abundance of a garden. They lived in close communion with their god and had a long life–and apparently a vegetarian diet. Their Utopia vanished in much the same fashion as the Golden Age: an outsider, portrayed as a serpent, introduced them to the Socratic method. Being subsequently banished from Eden, they could not re-enter, as the gate was guarded by an oscillating and presumably righteous sword of flames.

Shambhala, our third stop on the Silk Road, lies unreachable in mountainous ranges of Tibet. It is commonly considered a place of peace and happiness, ageless living, and universal enlightenment. The Dalai Lama considers it unreachable by the average person; it can only be found by someone with a special karmic connection.[i] In apparent contradiction to this, it has been vigorously sought by Nazis, Soviet communists, Theosophists, hoteliers, and garden-variety British adventurers. But a land of purity is seldom entered by people with uneasy obsessions.

Equally unreachable is the land of the Peach Blossom Spring. This legendary Chinese utopia is found in a fable dating from 421 CE.[ii] The story tells of a fisherman who happens upon a grove of peach trees. Exploring further, he comes into a glen bustling with happy activity. The inhabitants tell of their ancestors’ flight from civilization many centuries prior, and how presently they will never leave. They entertain him for a week, after which he departs. They admonish him to never seek their utopia again. Although he marks his path on the way out, he can never find his way back.

Off the menu, and as off the road as the Peach Blossom Spring, is the Village Green of one Raymond Douglas Davies, CBE. He is more commonly known as Ray Davies, principle song-writer and leader of the Kinks.

“Out in the country/far from all the soot and noise of the city/there’s a village green.”[iii] These hardly seem to be subversive words. Yet in the late 1960s, as London was swinging, Detroit was burning, and San Francisco was tripping in a lysergic flower shower, Davies and the Kinks released a “suicidally unhip”[iv] album that set out to subvert the subversive. It didn’t actually work out that way, of course.[v]

Like the Peach Blossom Spring, few people knew of its existence. But to those who were able to find The Kinks are the Village Green Preservation Society, Utopia was presented anew. Its thesis—that Utopia was to be found in a small life in the British countryside—sprang from the refusal to accept the world as it was. Equally rejected was the world as proposed by the counter-culture. Our only hope was to go backwards. We must return to “little shops, china cups, and virginity”[vi]—that is, we must expunge ourselves of modern complications and return to days of innocence in the garden.

Contrasting with the fits of violence in the real world around him, Davies’ songs present characters and scenes to serve as touchstones: childhood friends “Walter” and Daisy (she whom he kissed “by the old oak tree”); the motor-biking renegade “Johnny Thunder;” and the local prostitute, “Monica,” much adored as she stands knowingly and enchantingly under the street light. Even ready-made characters are presented for children’s admonition: “Wicked Annabella,” the local witch who will snatch up any children wandering past bedtime, and the flying “Phenomenal Cat,” whose worldly travels have led him to extreme omphaloskepsis.

Among the scenes are family celebrations, with laughter-filled photographs; the big sky, metaphorically standing in for the god of the garden; and the music hall, where performers embarrass and redeem themselves in front of their friends. In perhaps the strongest indictment against the world around him, Davies inhabits an “Animal Farm.” “This world is big and wild and half insane! Take me where real animals are playing!” Ditching the world where dreams often fade and die, he prefers the dirty old shack among the pigs and goats. You can have London, I’ll take Hooterville.[vii]

Reaching to a time before even the village green, Davies’ “Sitting by the Riverside” echoes the words of Zeng Dian, an early disciple of Confucius. When asked about his ambitions, he replied: “At the end of spring, with the spring clothes already been finished, I would like, in the company of five or six young men and six or seven children, to cleanse ourselves in the Yi River, to revel in the cool breezes at the Altar for Rain, and then return home singing.”[viii]

All Utopian writings—from St. Thomas More’s Utopia to Plato’s Republic and the Tao Te Ching of Lao Tzu–carry with them a disdain for the present world. But they also carry a strongly fabricated nostalgia. In the case of Village Green Preservation Society, Davies was noted as “pining for a simpler, quieter England that probably never existed.”[ix] Like him, we continually insist that the place of perfection did once exist. Enthuses Davies in “People Take Pictures of Each Other:” “People take pictures of the summer, just in case someone thought they had missed it, just to prove that it really existed.” Such emphatic insistence that the alternate world is actually real: this is what gives Utopia its strength. We really believe we can get there.

In the philosophically Eastern world, perhaps, but not so much in the Western.

Lyman Tower Sargent, Professor Emeritus of Political Science at the University of Missouri-St. Louis and Utopian scholar, writes of the key contrast between Western and Eastern utopian traditions: It is the presence in Western myths of a Fall, an act of transgression which irreparably ruptured our relationship with the god(s).[x] We are therefore no longer fit for their kingdom. The best we can hope for is an increasingly degrading existence until such a day as Christ returns. For some Christian philosophers, “Utopian thought is itself evil.”[xi]

Conversely, writes Sargent, Eastern traditions have no Fall, no traumatic loss of relationship and place. We still retain the formula for paradise. We can regain the bliss of the Peach Blossom Spring if we would simply follow the formula as it is given. It is ever present with us, if we will stop fighting against it.

As for our hero in Village Green Preservation Society, he chooses unwisely. Just outside the village was that silky, seductive, serpentine road “I sought fame,” he tells us matter-of-factly. Two lines later he laments, “I miss the village green, and all the simple people.” He feels that he cannot return, for his world is now too big to fit into the small life. The villagers might find his worldly self a bit much to take, also. As Michelle Shocked states in “Memories of East Texas,” “Their lives ran in circles so small/they thought they’d seen it all/and they couldn’t make a place/for a girl who’d seen the ocean.”[xii] There’s only so much outer world that Utopia can bear. That’s why the route to the Peach Blossom Spring remains hidden. As for Shambhala, the Dalai Lama has presumably sealed that route for everyone but himself.

This longing to return to a place already built upon nostalgic fantasy maps well against the contemporary vogue of sustainable living and backyard-DIY. Yet, ever like Voltaire’s Candide, we must persevere long enough, and with enough hope, to establish and tend to our own gardens. We must subvert the notion that Utopia cannot be regained.

Luckily, the strength of utopian thought is its subversive nature.[xiii] It can be exercised anywhere at any time. Occupy Wall Street was a utopian experiment, as are monasteries, intentional communities, animal sanctuaries, and this humble supper club. They serve as antidotes for the perceived poisons of the world-at-large. They offer suggestions for a cure, and if their idyllic post-card portrayals don’t carry with them exhaustive instructions, they still provide glimpses of an alternative. That alone is motivational: you can’t climb the mountain until you see the mountain.

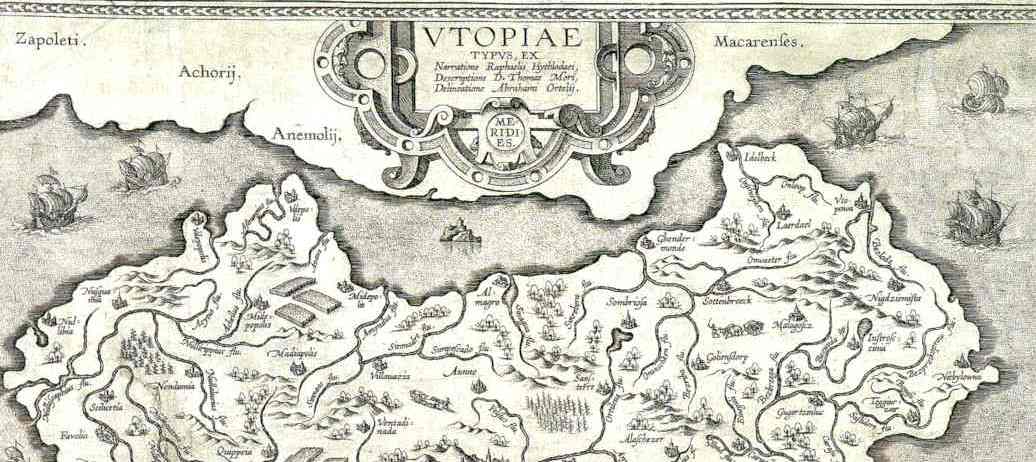

Oscar Wilde once wrote, “A map of the world that does not include Utopia is not worth even glancing at, for it leaves out the one country at which Humanity is always landing. And when Humanity lands there, it looks out, and, seeing a better country, sets sail. Progress is the realization of Utopias.”[xiv]

We iteratively establish Utopias as stepping stones, mile markers to which we can refer when our course needs correction. With each new stone, we are more resilient and capable, winnowing ourselves into the core of what matters. As the powers-that-be successively nudge us closer to calamity, we revert to the soil and the sun and the simple. In this sense of recursion, Utopia is Tao:

Small country, few people

Let them have many weapons but not use them

Let the people regard death seriously

And not migrate far away

Although they have boats and chariots

They have no need to take them

Although they have armors and weapons

They have no need to display them

Let the people return to tying knots and using them

Savor their food, admire their clothes

Content in their homes, happy in their customs

Neighboring countries see one another

Hear the sounds of roosters and dogs from one another

The people, until they grow old and die

Do not go back and forth with one another[xv]

Finally, to get back to supper club matters at hand, we wrap up with a quote from the inimitable Pete Quaife, whose exquisite bass lines adorn The Kinks are the Village Green Preservation Society: “The Kinks all agree that Sunday dinner is the greatest realization of heaven.”[xvi]

Welcome to Peace Meal Supper Club™ #6: Utopia. God Save the Village Green.

The Menu

Course 1:

Lemon Rice Soup ~ Dolmas ~ Pita

A reflection of the Golden Age of Greek legend.

Course 2:

Root Vegetable Braise ~ Licorice Root and Juniper Reduction

Edenic abundance from the Fertile Crescent.

Course 3:

Momos (Vegetable Dumplings) ~ Roasted Barley ~ Winter Greens Stir-Fry

Elusive Shambhala beckons from the Tibetan plateau.

Course 4:

Green Tea Poached Pear ~ Ginger Peach Pastry Cream

Peach Blossom Spring takes a Taoist twist into the Great Unity.

—————————

[i] http://thegrandshangrila.com/shangrila.php; This quote appears in numerous publications. I love that it is being utilized by a hotel. Irony!

[ii] http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/2090; a PDF of the fable is also here: http://afe.easia.columbia.edu/ps/china/taoqian_peachblossom.pdf

[iii] “Village Green,” http://www.kindakinks.net/discography/showsong.php?song=424

[iv] Andy Miller, “The Kinks Are the Village Green Preservation Society,” 33 1/3 Series, Continuum, 2007, pg. 43

[v] The album was almost universally and superlatively acclaimed by critics. However, it was a commercial failure. For a fascinating in-depth read, see the book by Andy Miller listed just above. The Wikipedia article on the album provides a good overview: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Kinks_Are_the_Village_Green_Preservation_Society

[vi] “The Village Green Preservation Society,” http://www.kindakinks.net/discography/showsong.php?song=425

[vii] Hooterville was the setting for two rural American sit-coms in the 60s, Petticoat Junction and Green Acres.

[viii] Shen, Vincent (2013). Dao Companion to Classical Confucian Philosophy, pg 77

[ix] Harold De Muir, “Brothers in Arms,” Pulse Magazine, 1993. http://www.davedavies.com/articles/pm_0593.htm

[x] Lyman Tower Sargent, “Utopianism: A Very Short Introduction,” Oxford, 2010, pg. 68.

[xi] Ibid., pg. 98

[xii] There was nation-wide concern over this phenomenon in post-WWI America. Nora Bayes scored a major hit in 1919 with “How Ya Gonna Keep ‘Em Down on the Farm? (After They’ve Seen Paree)”. I would be willing to bet that Ray Davies has this record in his collection.

[xiii] Sargent, pg. 123

[xiv] Oscar Wilde, “The Soul of Man Under Socialism,” 1891

[xv] Tao Te Ching, chapter 80. I am quoting Ellen Chen’s translation. “The Tao Te Ching: A New Translation with Commentary,” Paragon House, 1989.

[xvi] Miller, pg. 88