Dirt is perhaps the most under-respected culinary ingredient around. But try to cook without it and see how far you get.

More crucial for flavor development than onions or garlic, providing more balanced nutrients than classic 1970s food-combining, funkier and more complex than any fermentation process, dirt is seldom welcome in the kitchen. It is scrubbed off and swept out, lest it land on a diner’s plate.

But now and then, we should consider the world comprised by all those grains of dirt. Ecologist Peter Warshall describes it as a richly populated and bustling micropolis whose citizens vastly outnumber us.

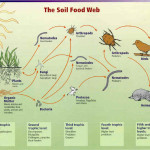

“One teaspoon of rich grassland soil can contain 5 billion bacteria, 20 million fungi, and 1 million protists. More microbes live in a teaspoon of earth than people on the planet.”

“Within the grand variety of earths, amoebas slide over grains of sand, hunting bacteria; bacteria swim through microrivers in search of nutrients; viruses puncture the bodies of bacteria and borrow their DNA; nematodes hunt and graze in teeming microforests of algae, devouring like hyenas almost anything that lives.”[i]

Over a square meter, the first few inches of soil contains thousands of ants, spiders, beetles, and fly larvae, along with thousands more of earthworms, slugs, and snails. Outnumbering them all are the nematodes, registering above 10 million.

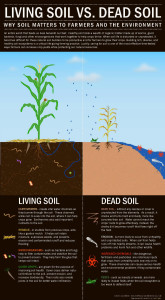

The roots of our food plants are not passive overnighters in this underground community. In a wonderfully complex symbiotic relationship, plants’ roots exude the proteins, carbohydrates, and other nutrients that the underground microbes need for survival. In exchange for all these “cakes and cookies,” as microbiologist Elaine Ingham terms these micronutrients, the bacteria and various other deep-dwellers bring the plant its much needed vitamins and minerals.[ii] Fungi spread their filaments, fostering trade over immense areas. Microbes build rain catchment systems, providing water management and drought resistance.

In a properly functioning closed-loop system, we would also be participating in the exchange, consuming the nutrient-rich fruits of these plants, leaving behind the inedible portions of the plants themselves, and returning the digested remains to the soil. All in the same area, keeping the system vibrant–very much like the rest of creation does.

Healthy dirt hums with activity beyond our imaginations. Yet puncture its surface, pour in foreign matter or withhold the natural exchange, and things can come to a standstill. The nutrient balance in the soil–that exchange of goodies between roots and microbes, bacteria and fungi–becomes compromised, sometimes to the point of complete breakdown. The effect is passed along to us, in the reduced nutrient content of our own foods and, eventually, completely unusable soil.

It is very easy to point the incriminating finger at modern industrial agriculture. While that is entirely appropriate, we must increase our depth-of-field: all agriculture contributes to degraded soil, and has for over 10,000 years.

Rattan Lal, Director of the Carbon Management and Sequestration Center at Ohio State University explains: “Nothing in nature repeatedly and regularly turns over the soil to the specified plow depth of 15 to 20 centimeters. Therefore, neither plants nor soil organisms have evolved or adapted to this drastic perturbation.”[iii]

One of the chief effects of all this plowing over the millennia is erosion. Environmental historian J. R. McNeill tells of three major ‘pulses’ of erosion worldwide, the consequences of each of which are still present with us today.[iv]

The first pulse began around 2000 BC, although we still experience its chief side effect: China’s loess plateau has been eroding for 3000 years. Present losses approach 2.2 billion tons of soil annually.

The second pulse occurred in the wake of the European conquest of the Americas, as European farmers used methods which were inappropriate for American soils. The effects of their actions reached into the 20th century, as dust bowls clouded skies around the globe.

Large-scale industrialization of agriculture in the 1950s kicked off the third great pulse. As a consequence, American farmland still loses topsoil about 17 times faster than it is formed.[v]

David R. Montgomery, Professor of Earth and Space Sciences at the University of Washington, states it this way: “The world’s farmlands erode as much as the high Himalaya…Think about it: it’s quite a trick to make flat-as-pancake land behave like the highest mountains in the world. We’ve managed to transform Iowa and Kansas into places that erode like Nepal.”[vi]

Plowing, that ancient technique so central to modern farming, dislodges root systems, triggers evaporation of the water stored in all those microscopic rain barrels, and disrupts the trade among plants and microbes. The soil’s population dies due to starvation and thirst. Additionally, plowing exposes the soil’s carbon stores to oxygen. These two rekindle their ancient love affair: they join to form CO2, and head for the atmosphere to alter our climate. It is estimated that land misuse accounts for 30% of the carbon emissions entering our atmosphere.[vii]

But it’s not just the plow that is wreaking havoc with our soils. One of modern agriculture’s hallmarks is the chemical enhancement of soil. In mid-1800s, wealthy countries began importing Chilean and Peruvian bat guano to enrich their fields. In 1842, an English farmer named John Lawes developed a method for producing artificial phosphorous. This was followed by the more the complex developments of Franz Haber and Karl Bosch in the early 20th century, which yielded artificial nitrogen. Up till then, nitrogen had been produced only by lightning and the bustling symbiosis of the underground.

Other artificial nutrients were developed, and by 1940, 4 million tons of industrial fertilizer were used worldwide. By 1965, that total had risen to 40 million tons. In 1990, 150 million tons were utilized. McNeill considers that this “development was and is a crucial chemical alteration of the world’s soils with colossal economic, social, political, and environmental consequences.”[viii]

McNeill states with chilling understatement that the long-term effects of the use of industrial fertilizers is unclear. In other words, we are still conducting the experiment, in the field, on our sustenance, daily.

Whatever the final outcome, the current observed truth is that these artificial inputs disrupt the communal exchanges in the soil web. They completely alter the nutrient exchange, and when combined with the use of herbicides, fungicides, and pesticides, reduce the soil’s population to nil. In Peter Warshall’s words, soil has become “simply a utilitarian medium in which to grow profitable crops–a substrate which can be improved upon and re-engineered.”[ix]

Lost is the symbiotic relationship between fungi, bacteria, and plants. Lost are the microrivers and microforests, with their battling microbes. The worms are gone, as are the millipedes and centipedes, beetles, ants, spiders, and slugs. Absent are the nutrients, those hotly traded commodities of the underground markets–which means that they no longer filter upwards into the foods we consume. There are some gains, however, in the form of unhealthy pathogens, soil compaction, and the tendency towards erosion and flooding.[x]

Some have rightly described agriculture as an extractive process, similar to mining. We take out, but do not put back. Consider some of the world’s major crops, those which are grown in massive monocultures and traded internationally: coffee, bananas, citrus, cacao, and even beef. They extract the nutrients from the soils where they are grown. The nutrients travel with these products into other countries, often on distant continents, never to return. The ideal closed-loop process I mentioned earlier is shattered, no part of it remaining intact.

This happens not only with our present-day, internationally traded crops. It began long ago, as cities grew and foods were brought into their markets from outlying farms. The nutrients left the farm for the city, and the city rarely sent back the compost or waste products. The nutrients therefore flowed, and are still flowing, into the sewers, rivers, treatment plants, and oceans.[xi]

Poor agricultural practices are not a new thing, and even in our relatively new country they are as old as the hills. Yale professor Steven Stoll, in his book Larding the Lean Earth, recounts the crisis that hit the United States within decades of the Revolution: its soils were completely exhausted. The depletion of farmlands among the original thirteen colonies were a major impetus for western expansion. Unsurprisingly, the western lands–and the ones further west of those, all the way to the Pacific Ocean–were soon exhausted, too. Exhaustion of land is not a limited phenomenon: arable land is degrading worldwide, at a steady rate.[xii]

Amidst all these tangible losses are more esoteric ones, losses which touch upon our enjoyment of food. The dominant agricultural system produces a limited variety of foods, and it does so even out of season. This quite naturally results in a lack of flavor within specific foods and across the larger spectrum. Diversity among foods–just as among cultures–provides an unquantifiable dimension of enjoyment. It provides an adventurous backdrop for the simple act of eating: flavors become more distinct as we have a greater array to choose from. Seasonality allows us to enjoy these flavors at their peak. Locality allows for truly ripe harvests. And healthy soil transmits a full supply of nutrients.

Foodies and wine enthusiasts–winies?–talk of terroir, the sense of place that accompanies certain foods and beverages. Connoisseurs speak about the slope of the terrain, the vineyard’s proximity to water, fluctuations of temperature, and length of growing season being discernible in a single taste of wine. This almost mystical quality is also applied to chiles, tea, coffee, cacao, and San Francisco sourdough. Perhaps in the distant past it was also apparent in sweet potatoes, peanuts, basil, peaches, and every other food one should choose to eat. Do potatoes grown in Texas taste distinctly different from potatoes grown in the Andes? Perhaps. But with our soils under such duress and being artificially manipulated, the days of terroir might be coming to a close. We are well into the age of homogenization.

But esoteric tasting aside, something larger is missing. It’s our connection to the soil. We shouldn’t need to be connoisseurs fixated on nuances. We should have pride in the things grown in the earth around us, by farmers who love their lands and nurture them in a sustaining and healthy manner. We should value true craftsmanship, as opposed to mass production.

Yet the defining characteristic of our food supply is displacement. Soils are displaced through rampant erosion; nutrients are displaced by artificial inputs; soil-dwelling organisms are displaced by pesticides and fungicides; nutrition is displaced by emptiness. Croplands are displaced by deserts. Climate is disrupted. Social justice is compromised.[xiii]

As a chef, the esoteric qualities mentioned above do matter. But as a progressively-minded human, the displacement, disruption, and compromises matter even more. And as a food-dependent animal, the functioning of our soil matters the most. Dirt is life.

So what is to be done? We certainly cannot discontinue agriculture. But farmers can adopt more progressive practices, using a mix of old and new methods. Consumers can vary their approach too, in meaningful ways.

E Magazine, in its 2006 article “The Scoop on Dirt,” provides a succinct overview: “Progressive farmers can reduce damage to soils by reducing tillage, managing irrigation to minimize water loss (and hence salt build-up from evaporation) and planting cover crops. Planting wind barriers on hillsides and maintaining healthy grass cover on pastures can help prevent erosion. If streams run through a farm property, planting grassed waterways along the stream banks can help trap eroded sediment and bind it up, keeping it from entering and polluting larger water bodies.”[xiv]

Wes Jackson, noted agrarian and the founder of The Land Institute, advocates planting mixed crops in one field,[xv] much like the milpa practice of ancient and modern Mexico.[xvi] In addition, his institute is working on ‘perennializing’ crops such as wheat: growing perennials, as opposed to annuals, greatly reduces disruption of the soil.

In conventional agriculture, fields are often left fallow for a year, and this typically means they are devoid of any plants. More progressive farmers, however, plant cover crops during fallow years. Cover crops benefit the soil in multiple ways. For one, they reduce erosion due to wind. They provide a vibrant root network to protect against water erosion. They continue the energetic exchange among soil-dwelling microbes, and, of crucial importance, they help build nitrogen in the soil.[xvii]

By keeping the underground exchange intact, cover crops are also keeping flood-and-drought resiliency intact. In the estimates of Eliav Bitan, a policy associate at the Rodale Institute, even a modest mixture of cover crops–clover, alfalfa, lentils, vetch, fava–would result in a 90% reduction in sediment runoff. As a bonus, this practice would sequester a metric ton of CO2 per acre.[xviii]

Further, by utilizing a system of integrated pest management, wherein crop rotation and natural prey/predator relationships are encouraged, pesticide use can be greatly reduced if not eliminated.[xix]

We eaters have a progressive to-do list, also. Perhaps the biggest thing we can do upfront is to become more knowledgeable about our food. We have been passive consumers for too long, and this has enabled the development of a very dysfunctional system. Set aside time to read a few books, some of which are recommended below. Trade out some of the time you currently spend watching The Game of the New Orange & Black Throne, or whatever it might be. This is of far more importance.

Second, become a regular at your local farmers’ market.[xx] This is a common recommendation, because it really is crucial. Go weekly, get to know the farmers, let them know who you are, make them a part of your social circle. It’s not automatic like picking something off the supermarket shelf and going through the express lane. It’s far more than that. You’ll be engaging in your community in a meaningful way, which is something we all say we are missing.

While you’re getting to know your farmers, offer them your compost. Offer to deliver it to their farm. Then walk around their farm and let them tell you about how they feed their soil. They will be happy to have you in their world.

As an eater, include foods that are not the latest vogue. We all love heirloom tomatoes, but we also need to embrace legumes and other soil-feeders. We must make it profitable for farmers to engage in sustainable practices.[xxi]

Remember, even in the best scenarios, agriculture is tough on the land. The biggest single thing we can do is reduce its extent. This means, without apology or equivocation, that we must remove animal products from our diets. It is an indisputable fact: more than half the world’s crops are used to feed animals, not people.[xxii] To engage in the eating of animals is a deliberate act which actively worsens the problem.

Finally, those of us who are not farmers still need to restore our connection to the soil, to understand this vibrant underworld which supports us. Dr. Paul Hepperly of the Rodale Institute believes this is fundamental to our future. “We need people to grow something—tomatoes, raspberries, flowers—so they understand the land, returning soil to its rightful place in the very center of our lives.”[xxiii]

Yes, it is true: the most important ingredient in my cooking is dirt. It is the genesis of all the foods I enjoy. It provides bounty well beyond my needs. It will feed me forever, if I will return my respect. When I consider flavor development, nutrient supply, diversity, and deep-down satisfaction, the answer is dirt. Glorious, life-giving, sustaining and delicious dirt.

So, giving thanks to the dirt, here is the menu for Peace Meal Supper Club™ #7: Dirt.

Course 1:

Carrot Ginger Soup ~ Pine Nut Sour Cream ~ Seeded Sourdough Roll

Cake and cookies for the underground.

Course 2:

Golden Beets ~ Cover Crop Cocktail Salad ~ Sesame Miso Vinaigrette

Indulging a nitrogen fixation.

Course 3:

Pu’erh-Smoked Maitake ~ Ful Medames ~ Roasted Sweet Potato ~ Pinot Gastrique

The quest for terroir.

Course 4:

Tiramisu ~ Chocolate Espresso Syrup

Healthy soil is no trifling matter.

Recommended Reading:

Something New Under the Sun, J. R. McNeill

Fatal Harvest: The Tragedy of Industrial Agriculture, edited by Andrew Kimbrell

Dirt: The Erosion of Civilizations, David R. Montgomery

Larding the Lean Earth: Soil and Society in Nineteenth-Century America, Steven Stoll

The State of the World’s Land and Water Resources for Food and Agriculture: Managing Systems at Risk, United Nations and Earthscan

Assessing the Environmental Impacts of Consumption and Production: Priority Products and Materials, United Nations Environment Programme

How To Grow More Vegetables, John Jeavons

Notes:

[i] Peter Warshall, “Tilth and Technology: The Industrial Redesign of Our Nation’s Soils,” in Fatal Harvest: The Tragedy of Industrial Agriculture, ed. Andrew Kimbrell (Island Press, 2002), 221-222.

[ii] Kristin Ohlson, The Soil Will Save Us (Rodale, 2014), 29-30.

[iii] Ohlson, The Soil Will Save Us, 13.

[iv] J. R. McNeill, Something New Under the Sun (W. W. Norton & Company, 2000), 35-48.

[v] Warshall, “Tilth and Technology,” 224.

[vi] David R. Montgomery, Dirt: The Erosion of Civilizations (University of California Press, 2007), xi.

[vii] Ohlson, The Soil Will Save Us, 15.

[viii] McNeill, Something New, 25.

[ix] Warshall, “Tilth and Technology,” 222.

[x] Not to stray from the agricultural focus of this piece, but it must be said that another human activity contributes mightily to erosion and general soil disruption: construction. Exposed soils at construction sites erode at an alarming volume. Wal-Mart alone may be responsible for the loss of between 1.5 million and 11.25 million tons of topsoil. Tamsyn Jones, “The Scoop on Dirt: Why We Should Worship the Ground We Walk On,” E Magazine, September/October 2006, 34. Accessible online at: http://www.emagazine.com/magazine-archive/the-scoop-on-dirt

[xi] McNeill, Something New, 23.

[xii] Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, “Sustainable consumption and production,” FAO at Rio+20, http://www.fao.org/rioplus20/75189/en/; The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations and Earthscan, “The State of the World’s Land and Water Resources for Food and Agriculture: Managing Systems at Risk,” 113.

[xiii] I make this statement as I consider the Third World countries which supply us with most of our key crops. Cacao, bananas, coconuts, coffee–the list is long. Each of these crops leaves depleted soil in its wake, soil which the developed world will not have to deal with long-term.

[xiv] Jones, The Scoop on Dirt, 39.

[xv] Wes Jackson, ” Tackling the Oldest Environmental Problem: Agriculture and Its Impact on Soil,” The Post-Carbon Reader Series (Post Carbon Institute, 2010), 6.

[xvi] For more on milpas, visit the Sustainable Milpa Project: http://sustainablemilpa.blogspot.com/; also, the unrelated Milpa Project: http://www.themilpaproject.com/

[xvii] Ohlson, The Soil Will Save Us, 93-94.

[xviii] Ohlson, The Soil Will Save Us, 108.

[xix] Jones, The Scoop on Dirt, 38.

[xx] Local Harvest lists farmers markets around the country, even in your town: http://www.localharvest.org/

[xxi] Jocelyn Novak, “Why Chef Dan Barber Thinks ‘Farm-to-Table’ Isn’t Good Enough,” The Huffington Post, June 25, 2014. Accessible online at: http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2014/06/25/chef-dan-barber-a-pionee_n_5530207.html

[xxii] United Nations Environment Programme, “Assessing the Environmental Impacts of Consumption and Production: Priority Products and Materials,” 66.

[xxiii] Jones, The Scoop on Dirt, 39.