Peace Meal Supper Club™ #8: Cacao is about taking chances and trying to reconcile the expansive outcomes. It’s an engaging culinary challenge: take an ingredient which has been pigeonholed as ‘confection’ and use it as a major ingredient for three savory courses, appealing to a diner’s sense of adventure. Add the further challenge of following those three courses with a dessert that will still register as ‘chocolate!’ I was continually drawn deeper into rediscovery as I explored this wondrously complex food.

Our modern ideas of cacao are firmly cemented even though we have greatly repurposed it. For its initial 28 centuries of use it was the ritual drink of a privileged few: priests and kings among the Olmecs, then the Mayans, then the Aztecs.[1] After a vigorous vogue among European elites, it finally became as commonplace as vanilla, abundantly adulterated and sadly situated in plastic wrappers and paper cups. Distressingly, its journey to those wrappers required–and still utilizes–a multitude of forced, unpaid laborers.

There is an epoch-spanning story here, one which involves global conquest by 15th-century imperialistic powers, government-sponsored and church-sanctioned slave trade, and the destruction of indigenous culture. We are making progress regarding labor and fair sourcing, but the story is largely the same as it has been. Global economic forces have only gotten stronger and more insinuated since Columbus’ voyages.

In this case, the menu also offers tales of culinary experimentation, from the curious ancients who first ‘discovered’ chocolate to the novel trends of current-day molecular gastronomy.

To start with, the Olmecs would have never cooked with cacao. Neither would have the Mayans nor the Aztecs. To do so would have been analogous to a Spanish priest cooking with transubstantiated wine.[2] It took centuries for someone to use cacao in a cooked dish, and though we applaud their ingenuity, we have to cringe at fried liver dredged in chocolate and lasagna filled with chocolate and anchovies.[3]

All of these experiments aside, chocolate wasn’t generally eaten in solid form until 1847, following a major accomplishment by Fry & Sons in Britain. Their experiments in blending specific proportions of cocoa powder, sugar, and cacao butter allowed for bars to be cast, thereby providing the world with its first eating chocolate.[4] Our meal, however, will begin with a longer stride back in time.

Amuse Bouche: Aztec Prelude

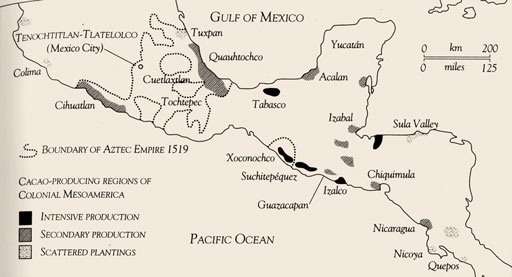

I vividly recall the galvanizing buzz that filled me as I sipped my first ‘ancient’ cacao beverage at Kakawa Chocolate House in Santa Fe. The impact was immediate, both physically and intellectually. I had ordered the ‘Aztec Warrior,’ three ounces of liquid intensity modeled after the drink enjoyed by Moctezuma, last of the Aztec emperors. He shared this beverage with Hernan Cortes in 1519, a deeply significant and darkly sinister communion with earth-shattering consequences. We can rightly vilify Cortes for his role in genocide and cultural destruction, but Moctezuma himself was far from innocent. His possession of cacao was a result of his own imperialistic urges. Cacao trees did not grow in Tenochtitlan, site of present-day Mexico City. He received his cacao as tribute from the peoples he suppressed in the Yucatan.[5]

Preceding the Aztecs in this cult of cacao were the Mayans (2000BCE to 900CE) and the Olmecs (1500BCE to 400BCE), the foremost pioneers in the story of cacao. It was they who discovered, through means unknown to us, the complicated process through which cacao seeds become chocolate.

First, the large fruit pods must be properly harvested. They are split open and the pulp and seeds are scraped out. They are left massed together and allowed to ferment. The seeds are then extracted and dried. After roasting, the seeds’ paper husks are winnowed away. The seeds are then ready for grinding into cacao paste.[6]

This process requires a very specific fermentation period, as well as particular roasting temperatures and duration. These two steps build flavor in the seeds, which upon harvesting are tasteless and odorless. This process was deciphered 4000 years ago–and it hasn’t changed since.

We have no clue as to what prompted this experimentation. Much like the domestication of corn, it is an unparalleled achievement in the food sciences. We have done nothing as substantial since.

Due to the labor-intensive process–not to mention the utterly delicious result–the seeds became a form of currency, and therefore too expensive for the common classes to drink away. As currency fosters trade, trade builds empires. Olmecs give way to Mayans, Mayans succumb to Aztecs. Enter the Spanish.

During that communion between Moctezuma and Cortes an observer noted the drink-making process. To date, it is the best ‘recipe’ we have of the ancient chocolate beverage. Though the observer is specifically describing an Aztec preparation, it is believed that the Olmecs and Mayans made their drink similarly.

“These seeds which are called almonds or cacao are ground and made into powder, and other small seeds are ground, and this powder is put into certain basins with a point, and then they put water on it and mix it with a spoon. And after having mixed it very well, they change it from one basin to another, so that a foam is raised which they put in a vessel made for the purpose. And when they wish to drink it, they mix it with certain small spoons of gold or silver or wood, and drink it, and drinking it one must open one’s mouth, because being foam one must give it room to subside, and go down bit by bit.”[7]

I have patterned our amuse bouche after this historic preparation.

First Course: The alchemy of the unexpected.

Roasted Cauliflower Soup ~ Cacao Caramelized Onions ~ Cherry Chocolate Sourdough

I have called the First Course “The alchemy of the unexpected.” It embodies the gruesome impact of the conquest, certainly, but also the culinary explorations that followed. Cacao has had an interesting post-conquest history, although most of it falls well within the political arena. On the culinary side, it has been a story of risk-taking.

Revered French chef Pierre Gagnaire has commented that “combining five ingredients to make a dish is taking five risks.”[8] Granted, the risks are artistic and not at all life-endangering. But they do challenge expectations and ask that diners be open to change.

Perhaps for that reason, most modern chefs will experiment lightly. Googling ‘savory cacao recipes’ reveals some very high-level chefs doing some very underwhelming things. Adding cacao as garnish to an arugula and speck salad, for example, is not really ground-breaking.[9] We must go farther. After all, cacao has one of the richest and most complex flavors of any food, according to food scientist Harold McGee. Within its 600 different kinds of volatile flavor molecules, a discerning palate can identify bitterness, fruits, wine, sherry, vinegar, almond, floral notes, nuttiness, earthiness, and spicy undertones.[10] Cacao really can do much more than decorate a salad.

It is no wonder then that cacao has been a favorite of food chemists like Hervé This, whose work is foundational to the modern trend of molecular gastronomy. Often misunderstood and quickly bastardized by the masses, this approach is described by McGee as simply the “scientific study of deliciousness,”[11] or in other words, an exploration of compatible flavors based upon an examination of molecular structures. For example, caramelized cauliflower shares key volatile molecules with cacao.[12] Might they be compatible in a dish? Sounds risky, doesn’t it? It also sounds intriguing.

Chemist and food enthusiast Martin Lersch leads an online community of flavor geeks who explore such scientific pairings. He posed this pairing in his regular “They Go Really Well Together” challenge. Community members posted their own findings, including recipes they had worked out. But a slab of roasted cauliflower accompanied by a block of gelled chocolate seems a bit austere for Peace Meal Supper Club™. We need something that feels more like home as it stretches our boundaries.

Now a creamy caramelized cauliflower soup sounds pretty homey. Garnish it with some onions that have been cooked slowly in a generous measure of cocoa powder. Then provide the real star attraction: take a generous measure of unsweetened cacao, couch it in the funk of an ale-based sourdough starter, and increase the drama with Bing cherries. The result is a bread with a smoky aroma and mellowed bitterness, with overtones of tobacco. It’s worthy of wine-speak. The soup and the bread fit into each other seamlessly, and on my palate I can sense a subtle shift from one to the next. It really is amazing. Soup and bread: looks like home, feels like home, and wow, it actually tastes like home, too. An accepting, progressive, world-changing home.

As we’ll see in the next course, our world does need progressive change. As modern as we are, we still procure our comfort through a very Old World method.

Second Course: Complex relationships and enduring flavors.

Tofu with Pomegranate-Cacao Rub ~ Shaved Fennel ~ Chocolate Stout Reduction

In the post-Columbian miasma, trade flourished and became truly global. Modern history can be viewed as the story of trade, as nations rise and fall based upon their ability to engage in worldwide economics. This is frankly how things operate today, as third world countries are evaluated–by industrialist and imperialist nations–based upon their financial potential.[13] They are encouraged to enter the global markets if the leading nations deem them valuable. These complex relationships have far-reaching impacts, not the least of which extend to third world citizens.

Since 1994, “the world’s poorer countries have been forced to open up their markets to foreign imports, while the rich countries [notably those in Europe and the USA] keep their markets more protected. Many have also been encouraged to maximize their foreign earnings by increasing their exports in order to pay off international debts. Land that was used to grow food for local consumption has been turned over to ‘cash crops’ such as coffee tea, cocoa, and horticultural products. This has led to countries becoming dependent on just a few crops for their foreign income. …Individual farmers…are extremely vulnerable to a drop in commodity prices on the world markets. They do not have any reserves to tide them over a bad patch, are often forced to sell their crop at less than cost price, and lose their livelihoods as a result.”[14]

In 1980, cacao was selling on the international market at 118.6 cents per pound. By 2000, it was selling at 40.23 cents per pound. Today it trades at 73 cents per pound.[15]

It is a simple fact: buyers benefit from a low price, but sellers do not. Another simple fact: the buyers–in this case developed economies–have a disproportionate influence over the selling price. Third world farmers and citizens lose.

Cacao was traded ‘internationally’ well before Columbus and Cortes. Some findings in New Mexico indicate that cacao was brought in from Mesoamerica in return for turquoise.[16] Large-scale trade also figured into the prevalence of cacao among the Aztecs; it certainly didn’t grow within their natural domain.

While trade will always happen anytime one group wants the product of another group, we are speaking of vastly different scales. Apart from the global aspects, we are also talking about the scale of cacao’s consumption: whereas cacao was used as an elite beverage in pre-Columbian Americas, it is now consumed daily in multiple forms by the average world citizen. In Britain, Germany, and Switzerland, the average person will consume about 24 pounds of chocolate each year. The industry itself is valued at $83 billion per year.[17]

Taking a crop into hyperactivity, as we have done with cacao, coffee, sugar, and other international commodities creates severe imbalances in economies. But while ‘economy’ can be considered an intangible chimera, third world poverty and human rights abuses are extremely real.

We must redefine our relationship with cacao, both as a consumable and as an actor in the lives of others.

Conveying the concept of change in a dish is a challenge in itself, as Hervé This and Pierre Gagnaire explore in their wonderful book, Cooking: The Quintessential Art. My style has always been simple, so playing this hand subtly suits me well. The use of cacao as a savory seasoning is different in its own right. There’s no need to be gauche about it.

Simply stated, I’ve paired cacao with pomegranate in a marinade for tofu. Tofu and cacao don’t meet regularly: the Chinese, originators of tofu, are not big chocolate fans. India and Iran, native homes for pomegranate, are also low consumers of chocolate. Perhaps we can follow their lead, and adopt a more sparing use. It is a powerful flavoring, and a little goes a long way, especially on a neutral substance such as tofu.

After marination, the tofu is baked in a paste composed of cacao, pomegranate, and tamarind. In addition, I’m preparing a reduction sauce using Samuel Smith’s Chocolate Stout. It is the very embodiment of bitterness, but it will be offset by a splash of pomegranate juice reduction. Served on a bed of shaved fennel, this dish, with its black-on-white color scheme and sweet-and-sour flavors, is the very embodiment of contrasts. Thus is the world of cacao, but the contrasts are not always this palatable.

Third Course: Hands across the waters, indigenous and ancient.

Roasted Winter Squash in Cassava Empanada ~ Jollof Rice ~ Mole Oaxaqueño

This course is about harmony, which is in a way a subset of contrast. While the Swiss are consuming record amounts of chocolate each year, in Ivory Coast, Ghana, Indonesia, Nigeria, Brazil, and dozens of other tropical countries cacao’s harvesters are subsisting on la comida de los pobres, the food of the poor.

For at the shorter end of that $83B economic stick live the people working in the cacao forests. In a 2012 story, CNN introduces us to one of those workers, whom they call Abdul: “He squats with a gang of a dozen harvesters on an Ivory Coast farm. [He] holds the yellow cocoa pod lengthwise and gives it two quick cracks, snapping it open to reveal milky white cocoa beans. He dumps the beans on a growing pile…Abdul is 10 years old, a three-year veteran of the job. He has never tasted chocolate.”[18]

And he is not alone. As the CNN investigation progressed, they found what many NGOs already knew: that “child labor, trafficking, and slavery are rife in an industry that produces some of the world’s best-known brands.”

It’s a long-standing tradition, beginning with the Spanish and Portuguese conquests in the Americas. Finding the indigenous people to be unwilling slaves, they imported West Africans to work their cacao plantations.[19] Later, cacao trees themselves also crossed the Atlantic, first to islands off the coast of Guinea, then into the African continent itself. European imperialists were then able to utilize forced African labor without the bother of transporting slaves across the Atlantic.[20]

Though we would like to consider ourselves past the practice of forced labor, this is sadly not the case. “UNICEF estimates that nearly a half-million children work on farms across Ivory Coast, which produces nearly 40% of the world’s supply of cocoa. The agency says hundreds of thousands of children, many of them trafficked across borders, are engaged in the worst forms of child labor.”[21]

Since 2001, the chocolate industry has garnered over a trillion dollars in profits. Only about .0075% has been invested to improve working conditions for children in West Africa. We shouldn’t even be talking about the working conditions of children, anywhere. We should be past this.

However, the problem of child slavery is so common in West Africa that Hershey, Nestle, and the US Congress once vowed to combat it. In 2001, eight major chocolate companies, three US Congressmen, several international ambassadors, and others signed the Harkin-Engel Protocol,[22] a non-binding voluntary agreement aimed at ending the “worst forms of child labor.”[23] Thirteen years later, the problems persist. “The issues are systemic,” concludes one researcher.[24]

Unsurprisingly, Fair Trade has become a hot topic for the chocolate industry. While it is far from perfect[25], Fair Trade Certification is a major step forward. It gives us consumers a great deal of influence. I’ve carefully selected the cacao products I’m using for this meal, and I deeply appreciate that they have been carefully produced as well.

There is a long way to go and a lot of meals to prepare. I’m thankful that my carefully directed dollars can help provide those meals. Perhaps they will look something like our Third Course: Roasted Winter Squash in Cassava Empanada, with Jollof Rice and Mole Oaxaqueño.

Cassava is a major staple food in the developing world, providing a basic diet for over half a billion people.[26] It is one of the most drought-tolerant crops, capable of growing on marginal soils. It is the third largest source of carbohydrates in the tropics–the region in which cacao grows. It also makes a wonderfully malleable dough, which in this course softly encloses roasted butternut squash. Termed ’empanada’ in Spanish, the form is almost universal.

Jollof rice is closely associated with the Wolof tribes of Senegal, but has spread throughout other West African countries. It is very similar to the pilaf of Asia Minor and some Spanish-influenced dishes of the Americas, with seasoned rice being sauteed briefly before it is simmered in stock. For seasoning, I’m using a traditional West African blend called tsire: roasted ground peanuts, ground chile, ginger, nutmeg, cinnamon, and clove. These warm spices are perfect complements for the bitterness of cacao; in fact, most of them have been mixed into cacao beverages for centuries.

Chile and cacao have a long history in the sauce we’re highlighting, Mole Oaxaqueño. It is not as ancient as the Aztecs, for they never considered using cacao in a sauce or other cooked form. Rumors abound as to the origin of sauces using chocolate, but the most likely story centers upon 17th-century Catholic nuns in Puebla, Mexico, who anxiously improvised the sauce to serve to their visiting bishop.[27] This makes for a wonderfully cinematic scene, a more peaceful blending of the New World with the Old, in a dish that distills a moment in time. My Mole Oaxaqueño is inspired by two very different Oaxacan chefs, Iliana de la Vega of El Naranjo and Nora Andrea Valencia of Casa de mis Recuerdos.

Admittedly the risks in this course are minimal. That is by design, as I was focused on cross-cultural yet universal sustenance of the people on the ground level. The food is always much better among the poor, and I say this respectfully without any irony. Their food is their consolation, so it is imbued with richness and passion as counter-balance to the troubles that reappear once dinner is done.

I have subtitled this course “Hands across the waters, indigenous and ancient.” The words are ambiguous: the hands could be those of oppression or of liberation. Which hands are ours?

A good time to answer that question is when you are buying chocolate or another cacao product. Are you picking up items with a Fair Trade label? Did your fingers do a little googling before you went shopping? Please see the websites listed below for help in choosing your chocolates.

Final Course: Brooklyn tryst with a twist.

Chocolate Egg Cream ~ Flourless Chocolate Torte

The risks return in the closing course, as I have to upstage every use of cacao in the preceding courses. Dessert is chocolate’s home turf, so subtlety is no longer on the program. Intensity takes its place.

First, the easy part: Brooklyn’s unofficial national beverage, the Chocolate Egg Cream. It contains no egg, and no cream. And not just because Peace Meal Supper Club™ is an all-vegan venue. These two ingredients have been a part of the drink only in name, and the definitive explanation for the misnomer is debatable.[28]

It seems fitting to include a modern chocolate beverage to bookend with the most ancient one. They are worlds apart. The older one was made from ground cacao, vanilla, and chiles, vigorously mixed with water. The modern one comprises, in the words of Lou Reed, “Some U-Bet’s chocolate syrup, seltzer water mixed with milk. Stir it up into a heady fro’–tasted just like silk.” The former beverage was ceremoniously poured from vessel to vessel to produce foam; the latter is simply stirred by a seltzer-wielding jerk.[29] We have just traversed the path from sacred to profane, it seems.

In such a journey, we find the distillation of not only pop culture, but our culture in general. While the mainstreaming of chocolate has its egalitarian victories, it has come at a tremendous price, where even human life is not deemed worthy of our consideration. Pondering the state of third world labor runs counter to convenience. There is a message in there somewhere if we will take the time to read it.

Our chocolate egg cream–which in deference to Mr. Reed is made with my own chocolate syrup and milk of a non-dairy source–is accompanied by a flourless chocolate torte, containing some degree of risk: black beans form its foundation. Their rich texture and mild flavor provide the perfect canvas for a mighty brushstroke of cacao. The result is a luxuriously smooth dessert that one could live on quite happily.

It wouldn’t be complete without a glossy covering, which I’m providing in the form of dark chocolate ganache. To make the dessert scream “chocolate!” a little louder, I’ve topped the ganache with buttercream flourishes composed of cacao butter. It’s another white-on-black contrast, reminding us that change is overdue.

It is true: chocolate is still the prerogative of the privileged classes. Those who labor in its production exist outside that privilege–and have for millennia. The world has changed for us, but not for them.

My hope is that my creative use of cacao will stimulate creative discussion regarding our rendezvous with progress. It should not be a surprise that our every action, every day, occurs at a crossroad of change. We either embrace it through enlightened choices, or we reject it by acting according to a legacy of status quo. It is our responsibility and privilege–I should say it is the responsibility of our privilege–to make great changes in the way the world operates.

Several organizations exist for the sole purpose of helping us make these changes.

The Food Empowerment Project “seeks to create a more just and sustainable world by recognizing the power of one’s food choices. We encourage choices that reflect a more compassionate society by spotlighting the abuse of animals on farms, the depletion of natural resources, unfair working conditions for produce workers, the unavailability of healthy foods in communities of color and low-income areas, and the importance of not purchasing chocolate that comes from the worst forms of child labor.” http://www.foodispower.org/

Fair World Project: “an independent campaign of the Organic Consumers Association which seeks to protect the use of the term “fair trade” in the marketplace, expand markets for authentic fair trade, educate consumers about key issues in trade and agriculture, advocate for policies leading to a just economy, and facilitate collaborative relationships to create true system change.” http://fairworldproject.org/about/introduction/

CNN Freedom Project: “CNN is joining the fight to end modern-day slavery by shining a spotlight on the horrors of modern-day slavery, amplifying the voices of the victims, highlighting success stories and helping unravel the complicated tangle of criminal enterprises trading in human life.” http://thecnnfreedomproject.blogs.cnn.com/

End Slavery Now “launched in 2009 with four features: an action database, an organization directory, learning resources and a store. The project’s founder, Lauren Taylor, envisioned a digital space that could empower every person willing to help end modern slavery and human trafficking. Along with providing tools, information and opportunities to everyday abolitionists, Taylor also wanted to help antislavery organizations increase their efficiency.” http://endslaverynow.org/

Something We All Can Do Today:

The Food Empowerment Project maintains a list of fair, slavery-free, environmentally-conscious chocolate manufacturers. Our purchases can easily be in line with those fighting for positive worldwide change. Their list is even available as a phone app. http://www.foodispower.org/chocolate-list/

Further Reading and Viewing:

Advocacy and Information:

End Slavery Now: http://endslaverynow.org/learn/photos/bitter-chocolate

The CNN Freedom Project: http://thecnnfreedomproject.blogs.cnn.com/2012/01/19/child-slavery-and-chocolate-all-too-easy-to-find/

Slavery, a Global Investigation (documentary): http://truevisiontv.com/films/details/90/slavery-a-global-investigation

Immaculata High School, Somerville, NJ: “The students and faculty of Immaculata High School are very concerned about the problem of child slave labor. Each year, the senior U.S. History II Honors class, taught by Miss Joann Fantina, publishes numerous newsletters throughout the year covering many aspects of child slave labor. A new group of students takes over the project each year as the previous class graduates. It is a common interest among the students and is continued enthusiastically year after year.” http://ihscslnews.org/

Industry Voices, for the sake of contrast:

http://www.thestoryofchocolate.com/index.cfm

http://www.icco.org/

Culture and History:

“An Act of Resistance,” an episode of The Perennial Plate online documentary series

Kakawa Chocolate House, Santa Fe, NM

The True History of Chocolate, Sophie D. Coe & Michael D. Coe, Thames & Hudson, 2013

_______________________________

[1] Sophie D. Coe and Michael D. Coe, The True History of Chocolate, Third Edition (Thames & Hudson, 2013), 232.

[2] Sophie D. Coe, “Mole,” in The Oxford Companion to Food, Second Edition, ed. Alan Davidson (University of Oxford Press, 2006), 513.

[3] Coe and Coe, 215.

[4] I am being a bit brief here. Fry & Sons based their experiments on the earlier advancements of Coenraad Johannes Van Houten. Following Fry & Sons were the Cadburys, Nestles, and Hersheys. See Coe and Coe, 234-253.

[5] As did the Maya before him and Cortes after him. Coe and Coe, 57, 176.

[6] Coe and Coe, 22.

[7] Coe and Coe, 84.

[8] “Rhythm and Risk in Cuisine: Chef Pierre Gagnaire.” Accessed February 23, 2015. http://www.starchefs.com/cook/features/chef-pierre-gagnaire.

[9] “How to use chocolate in savory dishes.” Accessed February 23, 2015. http://www.bonappetit.com/people/chefs/article/how-to-use-chocolate-in-savory-dishes.

[10] Harold McGee, On Food and Cooking (Scribner, 2004), 702.

[11] “About Khymos.” Accessed February 23, 2015. http://blog.khymos.org/about/

[12] “Flavor Pairing.” Accessed February 23, 2015. http://blog.khymos.org/molecular-gastronomy/flavor-pairing/

[13] A rather unsettling portrait of this is the ProSAVANA Project in Mozambique. It is discussed in the following article from The Guardian, accessed February 23, 2015. http://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2014/jan/01/mozambique-small-farmers-fear-brazilian-style-agriculture.

See also http://www.grain.org/article/entries/4703-leaked-prosavana-master-plan-confirms-worst-fears. The project’s website is http://www.prosavana.com/index.php.

[14] Andy Jones, “Developing Trade,” in The Penguin Atlas of Food, ed. Erik Millstone, et al. (Penguin Books, 2003), 72

[15] http://www.icco.org/statistics/cocoa-prices/daily-prices.html, accessed February 23, 2015.

[16] “Prehistoric Americans Traded Chocolate for Turquoise?” Accessed February 23, 2015. http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2011/03/110329-chocolate-turquoise-trade-prehistoric-peoples-archaeology/. Also, Coe and Coe, 55.

[17] “Who Consumes the Most Chocolate?” Accessed February 23, 2015. http://thecnnfreedomproject.blogs.cnn.com/2012/01/17/who-consumes-the-most-chocolate/

[18] “Child Slavery and Chocolate: All Too Easy to Find.” Accessed February 23, 2015. http://thecnnfreedomproject.blogs.cnn.com/2012/01/19/child-slavery-and-chocolate-all-too-easy-to-find/

[19] Coe and Coe, 192.

[20] Coe and Coe, 196.

[21] “Child Slavery and Chocolate: All Too Easy to Find.” Accessed February 23, 2015. http://thecnnfreedomproject.blogs.cnn.com/2012/01/19/child-slavery-and-chocolate-all-too-easy-to-find/

[22] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Harkin%E2%80%93Engel_Protocol#Protocol_and_2001_Joint_Statement

[23] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Worst_Forms_of_Child_Labour_Convention#Predefined_worst_forms_of_child_labour

[24] “The human cost of chocolate.” Accessed February 23, 2015. http://thecnnfreedomproject.blogs.cnn.com/2012/01/16/chocolate-explainer/

[25] ” Fair Trade USA Undermines Fair Trade Principles and Producers to Accommodate Products Such as Hershey’s “Greenwashed” Chocolate.” Accessed February 23, 2015. http://fairworldproject.org/press-releases/ftusa-undermines-ft/

[26] “Cassava.” Accessed February 23, 2015. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cassava#cite_note-5

[27] Coe and Coe, 212-214.

[28] Jennifer Schiff Berg, “Egg Cream,” in The Oxford Companion to American Food and Drink, ed. Andrew F. Smith (University of Oxford Press, 2007), 204-205.

[29] I am not being rude here. For those who do not know, people who operated soda fountains were often called ‘soda jerks.’ http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Soda_jerk