By the age of six, I could circumscribe my world in song. I was not particularly precocious. My world was just small. Ultimately, it would be fractured by its own rebellious genesis.

Two genres of folk music marked out the poles of my preciously tiny planet. Heaven’s jubilee rang in one ear: a cappella gospel, sturdily founded upon the biblical injunction to make melody in the heart. In the other ear, however, was the music of the devil himself: alcohol-drenched, two-stepping, hell-raising honky-tonk, enticing one to sin not just in the heart, but with the entire body. Together, they formed an eternally reciprocal refrain: Saturday night sin prompted Sunday morning renewal. There was little room for anything else, particularly dissent.

Two genres of folk music marked out the poles of my preciously tiny planet. Heaven’s jubilee rang in one ear: a cappella gospel, sturdily founded upon the biblical injunction to make melody in the heart. In the other ear, however, was the music of the devil himself: alcohol-drenched, two-stepping, hell-raising honky-tonk, enticing one to sin not just in the heart, but with the entire body. Together, they formed an eternally reciprocal refrain: Saturday night sin prompted Sunday morning renewal. There was little room for anything else, particularly dissent.

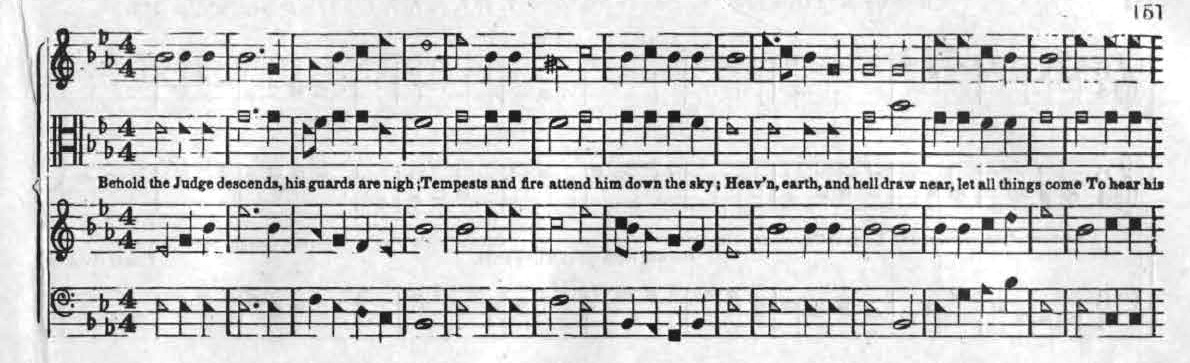

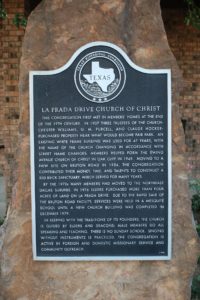

Sunday morning’s renewal resounded with four-part harmony based on a shape-note system of musical notation, widely referred to as Sacred Harp. We sang again at our Sunday evening and mid-week services. Throughout the year, we also hosted regional “singings,” bringing together folks from other congregations, swelling our own sound by double. Our a cappella songs were performed by the whole congregation, some singing the melody in unison, while others ventured into alto, tenor, and bass. It was an easy form of music to learn by design, with its origins in early 19th-century America. Its strongest base was in the south, and I inherited at least two generations’ worth of experience. It set the tone for my interactions with the world for the first three decades of my life.

Musicologists have documented and analyzed Sacred Harp thoroughly, with Alan Lomax having had a particular fascination for it. He considered it as not only an extension of four-square Anglo forms, but also as the crossroads where the Reformation met the Democratic Experiment. In Lomax’s view—expressed in a 1982 interview at the Sacred Harp Convention at Holly Spring, Georgia—European migration to colonize America broke the established authority of the church, leaving every person to forge a singular relationship with God. This supposition harmonizes perfectly with the views of the congregational church I attended. We had no hierarchy, no choir, no piano. Every man, woman, and child added their voice, as best they knew how, to raise an egalitarian song of praise. Songs such as This World is Not My Home, The Glory Land Way, and Blessed Assurance exemplify the form: simple AABB or ABAB rhyme schemes; closely-yoked shifts in harmony and rhythm; and southern gospel’s initial shunning of poly-rhythms or syncopation.

For me, Sacred Harp music created an immersive and experiential soundscape. During church services, it physically surrounded me. Each song engaged multiple senses. I read the notes and words on the page as I watched the leader mark time. My foot tapped along to the beat. I heard the voices around me as the sanctuary filled with song. The immense sound vibrated the pew on which I sat. Emotionally and spiritually motivating, it was the sound of temporal and eternal life.

Significantly, our church services matched the structured nature of our songs. Typically, we began our services with four songs, perhaps Victory in Jesus, I’ll Fly Away, Salvation Has Been Brought Down, and It Is Well With My Soul. A male member of the congregation then lead us in a lengthy prayer. We sang another song, and then listened to a sermon delivered by another male member. His message was followed by a “song of invitation,” which compelled any sinners in the congregation to come forward for a supportive prayer or perhaps baptism. Communion—practiced weekly—was held next, then we joined in a final song as a parting benediction.

Like our singing style, there was little room for improvisation. Flat-footed, reliable, and well-structured, our church service presented a model for our lives outside the sanctuary. “Trust and Obey” was a frequently sung hymn—and it summed up our approach to life in all matters. Obedience was expected, deviation discouraged.

Though I sang in church three times a week, the majority of my Sacred Harp education came during an annual singing school held by my home congregation. This weeklong event focused on raw, god-given talent and the power of personal involvement in meaningful music. It was a process which ethnomusicologist Tim Rice, in “Reflection on Music and Identity in Ethnomusicology,” would call “authoring the self through music,” in a way which creates a “sense of belonging to preexisting social groups.”

Adger Cowans/Getty Images

Worlds away from my encapsulated existence, civil rights leaders embraced a cappella singing as a powerful means to encourage, motivate, and activate. U.S. Representative and civil rights icon John Lewis says it concisely in the 2009 documentary Soundtrack for a Revolution: “It was the music that created a sense of solidarity.” His a cappella community was of the streets, challenging the status quo, and seeking greater brotherhood. Mine was by the book, increasingly authoritarian, very narrow in scope and population. We were a religious minority, and we soothed ourselves with Jesus’ statement that “many are called but few are chosen.”

To us, the New Testament authorized one and only one instrument for offering songs to God: the unaccompanied human voice. The root of this belief was a concise motto coined in the early 1800s by Alexander Campbell, a leader in the Second Great Awakening: “Where the Scriptures speak, we speak; where the Scriptures are silent, we are silent.” Applying this principle, then, the apostle Paul, in his epistles to the Ephesians and the Colossians, encouraged Christians to sing. But nowhere did he or another New Testament writer suggest using an instrument. This silence equals prohibition. Even the clapping of hands is forbidden. It’s an austere form of interpretation, one which promotes a hard-line, commandment-based faith, wherein permission must be granted for every action. And it sets its own reality, ignoring abundant biblical evidence to the contrary: the Old Testament presents many examples of instruments used in worship, as does the New Testament Book of Revelations.

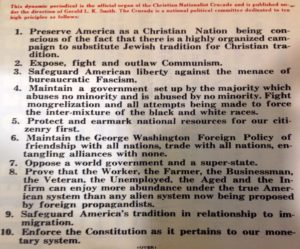

Our a cappella song service was therefore more than a sound—it was a belief system, a worldview in which other sounds or ideas were alien. We applied Campbell’s principle across-the-board, backing ourselves into very inconvenient corners: slaves were to obey their masters; wives were to submit to their husbands; and children were to be fully subject to their parents. These and other injunctions did not question the institution of slavery, admit the possibility of domestic violence, or even consider the presence of child abuse. They did, however, reveal a strong tendency to support authority, regardless of the morality, fairness, or temper of said authority. Modern movements towards an equal society—civil rights, gender equality, formation of labor unions—were viewed as threats to the established and god-ordained order. Questioning authority, let alone defying it, was strongly condemned by Paul in his letter to Christians in Rome: “Let every soul be subject unto the higher powers. For there is no power but of God: the powers that be are ordained of God. Whosoever therefore resisteth the power, resisteth the ordinance of God: and they that resist shall receive to themselves damnation.”

The message was uniform and tenaciously non-progressive: obey all forms of authority and await permission to act. As a religious body, we were anachronistic and socially regressive. As individuals, we were conditioned to tune out dissenting voices, in spite of our own rebellious origins.

Like politics, religion offers some incongruent bedfellows. As I was growing up, my Sacred Harp was both challenged and validated by an unlikely and unruly roommate: Classic honky-tonk.

The songs of Ray Price, Lefty Frizzell, Webb Pierce, and George Jones flowed like wine from the family record collection and radio settings. Their odes to sin filled our suburban tract home, the cab of my father’s pickup, our fishing boat, and the cabin at our weekenders’ farm in east Texas.

Songs of murder, drunkenness, alienation, revenge, adultery, and the workingman’s blues are staples of the honky-tonk catalog, drawing from the rich topical soils of its Appalachian legacy. Its celebrated ethic of “three chords and the truth” favored individual talent, community learning, and a rural do-it-yourself ethic. Based on historic and portable melodies, it valued memory over literacy. That is, one needed not be a Shakespearean poet to connect with these songs. Their construction resembled that of Sacred Harp: ABAB or AABB rhyme schemes, uncomplicated rhythms, simple vocabulary, with the addition of folk instrumentation. More importantly, an uneducated person could commit the songs to memory and understand them as they related to themselves. Twangy and resistant, honky-tonk seemed to defy the innovations and complexity of modern life. It was a matched bookend for Sacred Harp.

Songs of murder, drunkenness, alienation, revenge, adultery, and the workingman’s blues are staples of the honky-tonk catalog, drawing from the rich topical soils of its Appalachian legacy. Its celebrated ethic of “three chords and the truth” favored individual talent, community learning, and a rural do-it-yourself ethic. Based on historic and portable melodies, it valued memory over literacy. That is, one needed not be a Shakespearean poet to connect with these songs. Their construction resembled that of Sacred Harp: ABAB or AABB rhyme schemes, uncomplicated rhythms, simple vocabulary, with the addition of folk instrumentation. More importantly, an uneducated person could commit the songs to memory and understand them as they related to themselves. Twangy and resistant, honky-tonk seemed to defy the innovations and complexity of modern life. It was a matched bookend for Sacred Harp.

My personal identity and social belonging resounded through these two musical forms. Not only were my family’s origins evident—modestly educated, white, working class—but also my cultural heritage. Centuries of Anglo folk songs set the foundation for both Sacred Harp and honky-tonk. Work songs, love songs, ballads, dance tunes, and drinking songs—sharing melodies between them—perpetuated themselves through generations, resulting in 20th-century forms spanning multiple industry genres.

Handed-down melodies and lyrics are easy to track in these songs, as Lomax, Robert Waltz, David Engle, and Steve Roud have done (Waltz and Engle have an extraordinary database here; Roud maintains one here.) But the feature which emulsified my existence didn’t require research or folk music obsession. It simply required attentive listening. For in the background of many of those honky-tonk sounds, whether they were about larceny, war, or revenge on the boss, I heard the same harmony that filled my church.

In the 1950s or so, southern gospel groups such as the Jordanaires, Blackwood Brothers, and the Statler Brothers, began backing country music artists including Johnny Cash, George Jones, Tammy Wynette, and Gary Stewart. Their sonic presence lent an almost holy sanction to the commission of sin, as if Jesus and Satan met afterhours to share a drink and balance the books.

This sonic emulsification of sin and salvation formed my youthful identity and bracketed a very small existence. My world consisted of very gendered personal struggles: man vs. temptation; man vs. alcohol; man vs. boss; woman vs. womanizer. The solution provided for these struggles was always the same: the efficacious grace of God, which both helped me to fight my own sinful nature and urged me to offer salvation to others. All failings and victories were personal, not structural or systemic. The fight against personal sin was the only fight.

The essential truths of life had already crystallized in my brain when, at the age of six, I sat on my suburban front porch with a toy guitar in hand. Along with my brother, I sang Hank Williams songs for random passersby: Your Cheatin’ Heart and I Saw the Light. But the world outside my first-grader’s conceit was under siege, by forces far more devastating than a lonely man’s temptations. Wars were raging, cities were burning, inner cities were crumbling, treaties were routinely broken.

Social issues do not fit into a world composed only of personal demons. They require broader experiences and a willingness to break sound and subject boundaries. Williams attempted this, through his alter ego Luke the Drifter, but he was still singing from a hoary moralist score. Outside of the southern gospel-honky tonk complex, others knew better. Sam Cooke, battling multiple personas himself, knew that greater systemic problems needed to be addressed. His great risk in recording A Change is Gonna Come was lost on me. I never heard it, audibly or socially, just like I never heard We Shall Overcome, or Deportee (Plane Wreck at Los Gatos) or Here’s To The State of Mississippi. Even as I entered my 20s, my sonic defense system kept the sturm und drang of the real world at bay. If a lone dissenting cry managed to sneak through, I quickly dismissed it as exaggeration or the natural outcome of personal sin. I could not process a sound which conflicted with my god-given view of the world.

Southern gospel music and honky-tonk have enjoyed an institutional relationship since the founding of the Grand Ole Opry in 1920s. With a live program that consisted of white gospel performers and Appalachian string bands, the Opry—broadcasting from an erstwhile church—sanctioned the blending of reprobation and redemption. Its very name identified it with the down-home rather than the hifalutin.

Though initially politically ambivalent the Opry listed towards social conservatism during the 1960s—Johnny Cash’s nascent social awareness notwithstanding. In 1970, however, the Opry and the industry it represented found itself an unlikely accessory to Richard Nixon’s “southern strategy.” He declared October 1970 to be Country Music Month, and a few years later blessed the Grand Ole Opry with its first presidential visit. The Opry festivities consummated a perfect ménage a trois: the gospel and the government were openly opposed to sin. Taking honky-tonk as morality play, it was, also. All three, perhaps in spite of themselves, were pro-authority.

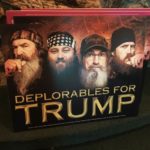

Politically conservative messages had entered country airwaves during the late 1960s, epitomized if not pioneered by Bakersfield stalwart Merle Haggard. His Okie From Muskogee ridiculed hippies, dope smokers, draft dodgers, long-hairs, flag burners, and college activists, all within a 3-minute single format. Though ostensibly written as a joke, it struck a chord among conservative, Christian, country music fans. Sensing a market, Haggard followed up with the flag-waving Fightin’ Side of Me, wherein he further shames pacificists. His cover of Ernest Tubb’s Soldier’s Last Letter—transferring it from its native World War II setting to the Vietnam War—crystallized the culture: war as commonplace; a son performing his duty; Mom, praying for all soldiers; and God on the side of America. Haggard’s songs did not always voice conservative ideas, but these songs are a soundtrack of politicized Christian identity.

I was just barely in grammar school when Fightin’ Side of Me hit the radio. I understood it about as much as I understood the Trinity, but I was more than able to walk around singing it. Its message harmonized with my developing law-and-order belief system. These songs, to state it simply, sounded right: three chords, simple language and concept, memorable chorus. Second, they contained the truth as I believed it: protestors, adulterers, and dope smokers were all in defiance of God. Besides, God had long tolerated war, slavery, and other social injustices. Haggard’s refrain in Fightin’ Side—“if you don’t love it, leave it”—made sense to me, and was safely non-challenging. Conveniently, the religious body of which I was a member had, a generation prior to me, actively opposed pacifism.

Long accustomed to seeing the sin in man, I did not recognize the sin in the system. I did not hear the discord between Haggard’s Working Man Blues and Tennessee Ernie Ford’s recording of Sixteen Tons. When confronted with inconsistencies, I assigned them to an individual’s behavior: Maybe ol’Ernie shouldn’t have taken that lousy job. Sam Cooke’s tribulations, Marvin Gaye’s inner city woes, and the deportees’ fate were likewise due to personal causes. I saw only men and women avoiding their duty and surrendering to temptation.

My mother frequently said that the lives portrayed in honky-tonk songs were not her life. But in another sense, those desperate lives, and the more hopeful ones portrayed in gospel music, were our lives collectively. We were part of a greater social identity: Southern, white, Fundamentalist, change-averse, full of latent conflicts. Those sounds, rich with heritage and lived-in context, formed us.

Our religious and social philosophy developed within coinciding but separate movements: the Second Great Awakening (mid-1700s to early 1800s) and the musical common practice period (roughly 1640 to 1940). Bound together, these streams of thought and practice rooted us in fixed meter, synchronized tonality, and observance of harmonic hierarchies. Each movement displays a notable absence of discord. Our obsession with harmony and predictable meter formed a very provincial vernacular and comprehension, turning sideways the words of 20th century philosopher and revolutionary Frantz Fanon. In Black Skin, White Masks, he suggests that “a man who has a language consequently possesses the world expressed and implied by that language.” In other words, our vernacular limited our hearing. Our world was formed within a fixed sonic boundary, and discordant sounds were ignored, resisted, or, if necessary, combated.

Within this soundscape, I had never heard of any march from Selma to Montgomery, not from church, family, the radio, or, sadly, even school. The larger movement of which it was a part—perhaps the biggest social movement of the 20th century—was inaudible and therefore irrelevant. When I did begin to hear of racial violence, I could only condemn anyone who defied authority. I did not know what to say about authority which abused the people. Raised to function in a law-and-order world, I could only repeat the Apostle Paul’s instruction that we all must obey authority or incur the wrath of God. I hoped that the trouble would die down, everyone would behave themselves, and we could let authority work things out.

But thankfully, the real world is a noisy place, and sound travels in subversive ways. Like through the transmitters of listener-supported community radio.

I found Dallas’ KNON completely by chance. Commuting to work through the city’s legendary rush hour, I’d get fidgety. Country radio of the 1980s left me cold. Classic rock stations were stuck in a corporate rut. Top 40 had never been my thing. While searching the dial, I heard a familiar song in an unfamiliar arrangement. I don’t recall the song now, but do remember its force: a honky-tonk classic played through a stack of Marshall amps, turned up to the proverbial ’11.’ Perhaps it was Leon Payne’s Lost Highway as rendered by Jason and the Scorchers—anarchistic, upending, challenging, it still carried enough familiarity to keep me listening. I stayed tuned in for the next song, then another. When the DJ, Nancy “Shaggy” Moore, signed off her show, I gave a listen to the next show—at least until they said something a bit too dissonant.

But the next day, I tuned in to Shaggy again. And I listened a bit longer when the next show came on. And even longer the day after that. Dallas at that time was wracked by racial strife, some of it focused on the politicized deaths of two police officers, one white and one black, in separate incidents. I had tuned out the duplicity, but KNON gave me reason to reconsider. City council member Diane Ragsdale, an African-American woman representing one of the city’s most trod-upon districts, refused to let the issue go. KNON provided the venue for her to express her outrage unmitigated, and to explain the inconsistencies in a way that an entitled white suburbanite, such as I, could understand.

Tim Rice suggests that we are not free agents in the creation of our identities—but given the right stimuli, we will resist, to the point of rebellion, the personhood prepared for us. The social unrest encircling my personal Jericho challenged my six-year-old’s concept of the world. When I heard of the launch of Operation Desert Storm in January, 1991, the foundations began to crack. Called out by name in the newscast were missile systems I had helped build while working at Texas Instruments in the early 1980s. Behind the newscaster’s voice were the sounds of the missiles themselves. My earlier justification of the missiles’ existence—“dear God, keep America free” Tubb and Haggard had sung to me—collapsed in that sonic assault.

Lomax considered Sacred Harp to be a rebellious form of music, breaking away from established authority and orthodoxy. Honky-tonk also carried a rebellious pedigree, chafing against accepted morality and aesthetic. This latent heretical ethic finally responded to the sonic stimuli flowing through the breach, triggering an insatiable devil’s advocacy: “Prove yourself to me,” I said to everything I had once believed, religious faith included. St. John wrote in his First Epistle: “Beloved, believe not every spirit, but try the spirits whether they are of God.” This was to be the last biblical directive I would follow.

My religious, political, and cultural beliefs were not the only casualties of this deconstruction. I ended my professional career as well, having understood the devastating effects that high tech industries have on the environment and workforce. I traded a six-figure salary for minimum wage in foodservice. Not once have I looked back.

Kitchen work comes with immersive sound: machines hum and sometimes roar; the radio blasts through the static; humans must shout in order to be heard. Working throughout the western US, in a variety of independent restaurants, I learned to understand and speak Spanish. I participated in defying a language ban placed on my colleagues by an overbearing owner: I noted that she forbade speaking in Spanish, but not singing in Spanish. So sing we did, about needing a potato peeler, taking out the trash, and what we were going to do over the weekend.

As I worked my way up the ranks and crossed the country from California to Manhattan, I listened to the stories told me by immigrants from Mexico, Guatemala, Dominica, Morocco, South Africa. They shared their music with me, via radio, iPod, cassette, or any object we could plug into an overcooked boom box. Every song and conversation has pulled me into greater participation in their lives and the systemic issues faced by most of the world around me.

Dissent comes in myriad expressions, and for me it has come via my own three-chords-and-the-truth and through a multimedia socially-progressive dining event which I call Peace Meal Supper Club. Its very raison d’etre is to illuminate dissonance on issues such as the right to sanctuary, our diminishing seed supply, the plight of the rural poor, and other devastating threads of intersectionality. Music is a critical component of each event, as Otis Taylor, Lila Downs, and Caetano Veloso share playlist space with Manecas Costa and Majida El Roumi Baradhy. Old favorites like Sixteen Tons get their say, as well—for behind that song’s well-earned swagger is a system of devastating intersectionality which needs our action.

Dismantling one’s identity, regardless of how deliberately it is done, happens amidst lots of noise: illusions shatter, idols crash to the ground, walls tumble into rubble. There is hope in this, for the creation of the universe has long been associated with big sound: the Big Bang, the booming primeval “Let there be light,” or even the Vedic “OM.” Once the reverberations ceased and silence settled in, I realized that I could fill the space—a universal space—with the sounds of my choosing.

Simon Frith’s words could easily be my own: “It is in deciding—playing and hearing what sounds right—that we both express ourselves, our own sense of rightness, and suborn ourselves, lose ourselves, in an act of participation.”[i]

=================

[i] Simon Frith, “Music and Identity,” in Questions of Cultural Identity, ed. Stuart Hall et al. (Sage Publications, 1996), 110.