It’s a well-documented fact that is rarely discussed: Hubris and Irony can’t keep their hands off each other.

In 1899, drought hit the lower Mississippi valley keenly, affecting cotton, sugar cane, and potato crops. Drinking water was scarce. Rice farmers were desperately pumping water over the levees in order to save their rice crops. It was the third drought in the decade, being preceded by those in 1896 and 1893. Less than 200 years prior, the area had been a wetlands, free of levees, pumps, and desperate farmers.[1]

The 1893 drought had been preceded by floods. Historian Christopher Morris considers this a sure sign that the region had become unstable, the result of systematic yet chaotic attempts at environmental transformation through the use of physical barriers. Instability has been a Mississippi River trademark for almost 300 years now.

“From almost the moment in the early 18th century when the French started to build New Orleans, settlers built levees, and in so doing, entered into a complex geoclimactic relationship with about 41 percent of the United States,” states Alexis C. Madrigal, a contributing editor for The Atlantic.[2]

The first levees were put into place by the French planters, in a model perfected by Joseph Villars Dubreuil in 1725 and constructed by his massive slave labor force.[3] It proved so effective that his neighbors took him to court. By modifying the river’s flow around his plantation, he flooded others. In some cases, he had inadvertently reversed the flow of water through his neighbors’ mills, rendering them inoperable. The Louisiana Superior Court ruled that a larger levee be built, with no openings for mills. As Morris succinctly states in The Big Muddy, “The solution to flooding caused by leveeing and draining was more leveeing and draining.” Hubris whistles. Irony whistles back.[4]

Behind the levees lay the philosophy that man can control nature, no matter the scale. The Europeans that came to the Americas did not intend to live on the land as it would have them. They intended to have the land as they wanted it. Continues Morris: “Levees reconfigured the human relationship with the environment, by separating land and water so as to enhance human control over both. Water touched land when people permitted it to do so, for example, when it flowed through man-made ditches and sluices, sawmills and irrigating fields…[Levees] transformed the river from a ‘destructive’ power into a force for ‘improving’ the land…human power triumphing over nature’s power.”[5]

When Hernando de Soto first visited the Mississippi River Valley in 1541, he observed one of the planet’s largest natural wetlands, extending over 35,000 square miles, with a watershed stretching from modern-day Montana to western New York. The French, following 130 years after de Soto, considered it unlivable in spite of the natives that were living there. They set about creating dry places to live and farm, inspired by the efforts of Dubreuil.

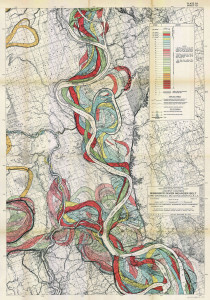

America has transformed the French experiments at containment into a grand-scale display of power over the environment. The 3500-mile system of levees within the Mississippi River basin rival the Great Wall of China in accumulative length, reaching across 40% of the continental United States.[6] In addition, 27 dams are situated between the river’s origin in north central Minnesota and St. Louis, Missouri. Other containment systems occur along the remainder of the river’s journey to the Gulf of Mexico.

Though championed for the benefits they provide humans, levees and other water containment systems are not benign fixtures on the landscape. They bring very serious side effects. As authors Friese, Kraft, and Nabhan write in Chasing Chiles, “A long, convoluted chain of events is causing the rising waters in the Mississippi delta. Human activities have interrupted the cyclical rejuvenation of the delta lands, from the construction of dikes and dams on the Mississippi River itself to the creation of other canals, channels, and diversions, which are the main drivers causing the subsidence of the delta and its islands in the bayous. As these lands disappear, there is a subsequent loss of coastal wetlands, and open water replaces marshy vegetation.”[7]

Naturalists, agroecologists, foodies, and culture freaks often decry the uncountable losses in such a scenario. But for the powers that be, these impacts are often measured in terms of economic gains. That’s because economy has always been the yardstick.

We cannot overestimate the economic force behind the locks, dams, levees, and canals that escort the river to its delta. In that delta lie three major shipping ports, which are absolutely critical for the US economy. The Port of New Orleans is the fifth largest port in the United States based on cargo volume. The Port of South Louisiana, also located in the New Orleans area, is the world’s busiest in terms of bulk tonnage. Taken in combination, the two ports comprise the world’s fourth largest port system in terms of volume handled. And of course, there is oil.

The ports were a long time in the making, but economy was always their impetus. LaSalle’s claiming of the Mississippi River on behalf of France in 1682 allowed for a massive trade network to be developed, reaching from the Gulf Coast to Montreal. The fledgling French settlements in Louisiana were an extension of economic desperation back home, as the French government fought its way through the monumental debts accumulated by the recently-deceased Louis XIV. Under the direction of Scottish financier and compulsive gambler John Law, the French hoped to reconcile debt through the sale of shares in the French Mississippi Company, the products of which originated in the American colonies. The Mississippi mania that infected Paris in 1719 is legendary, as commoners and nobles alike literally fought in the streets to obtain shares of the French Mississippi Company. It all came crashing down in 1720, threatening complete ruin to the French state.[8]

As the Duke of Orleans cleaned up matters at home, inertia had its way with Louisiana. To support the demand for product and profit–in the form of rice, indigo, sugar, or eventually cotton–French settlers exiled more of the great river, cleared and dried more land, deforested greater acreage, and applied a larger number of forced laborers. Between 1719 and 1731, the company established by John Law brought an estimated 6000 slaves from Africa.[9] The company attempted to relocate French debtors to Louisiana.[10] It succeeded in bringing in German debtors.[11] Their settlements along the Mississippi became known as The German Coast, home to the largest slave rebellion in United States history.

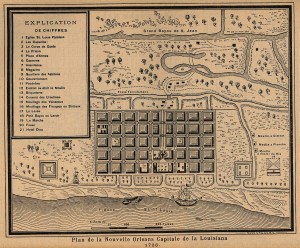

The French Mississippi Company scheme, though short-lived, had very long-term effects. For one, it reoriented the trade axis of French America. Illinois shifted its subordination away from Montreal and towards the port town New Orleans. Established in 1718 by Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne de Bienville on behalf of the French Mississippi Company, New Orleans was intended to be the economic capital of France’s American empire. The Mississippi River became the highway of imperialism. Like the river, all goods began flowing towards the Gulf.

The flow was profound. Cypress forests were felled to build the new city, and to make barrels for shipping the territory’s bounty. Along with timber, rice, beef, indigo, tobacco, sugar, and cotton traveled down the river. All of this necessitated more clearing of forests, more draining of swamps. The landscape was transformed from New Orleans to Illinois and beyond.[12]

The Louisiana Territory changed hands a few times between the mid-1700s and 1803, finally settling in US hands after negotiations between Jefferson and Napoleon. With US ownership came a boom in cotton production and slave labor. By 1860, the slave population in Louisiana, Arkansas, and Mississippi was approaching 1 million.[13]

Meanwhile, levees continued to grow in number and height. Referring to the Duke of Orleans’ role in the French Mississippi Company’s stock scheme, journalist Charles Mackay stated that “the regent…thought that a system which had produced such good effects could never be carried to excess.”[14] Professor Pangloss could not have said it better, even if he had seen all those levees.

Among those good effects immune to excess were massive fish kills due to toxic indigo runoff as early as 1800; comprehensive deforestation in some areas by 1900; domination of invasive plant species on land by 1800; infestation of invasive water species by 1880. In addition, all before 1900, there was increased flooding due to deforestation in the watershed regions of Pennsylvania and Ohio; coastal erosion at advanced rates; the need for protection of endangered animal species; and a collapse in natural prey-predator relationships at all levels of wild life.[15]

By the early 1800s, the soil was depleted “past all redemption,” according to noted agriculturist Solon Robinson. By 1920, chemical fertilizers were necessary throughout the delta. Since 1920, the large Sparta Aquifer, at the joining of Mississippi, Louisiana, Tennessee, and Arkansas, has dropped over 360 feet. Spectacular fish kills happened throughout the early 1960s, with 5 million dead between 1964 and 1965.[16]

This historical perspective is necessary for us to understand that the problems we face today are not new. That is to say, they are not a fad, nor a trend that will pass. They are endemic to the economic and political system we espouse. As I presented in past Peace Meal Supper Clubs™, most notably “Seed,” our system requires the constant production and sale of goods, on a scale that is excessive and destructive. This in turn requires complex industrial systems that do not serve the people, but instead funnel all resources to a nation’s bottom line. As for the people themselves, they are also considered resources to be managed for the good of the Gross Domestic Product.

To be clear, life was certainly not without its troubles prior to settlement by Europeans. But what de Soto found was a mix of peoples whose lives were fashioned around the activities of the river. When the river flooded, native people moved to higher ground until it receded. They consumed its proceeds and supported its replenishment. They subsisted on agricultural crops, fishing, and hunting, as we would expect. The caprice of the river provided inconvenience but not disaster.

The dynamic life of the Mississippi river system, pre-conquest, ensured constant replenishing of the soil with sediment drawn from the Rocky Mountains, the Great Lakes regions, and the western slope of the Appalachians. Cataclysmic flooding was infrequent. The vast Mississippi Alluvial Plain held some of the world’s richest agricultural soil.

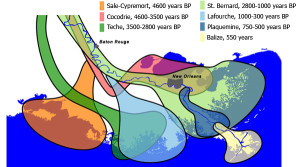

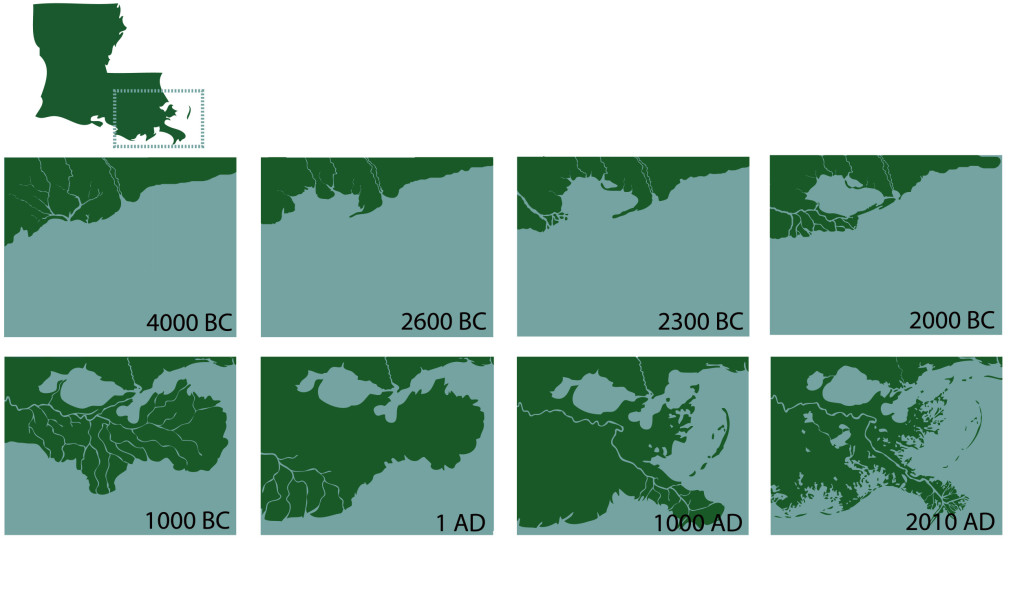

The river’s delta is the result of 7000 years of coastal sediment deposition. Through a series of shifts in the river’s course–known as deltaic cycles–these

The river’s delta is the result of 7000 years of coastal sediment deposition. Through a series of shifts in the river’s course–known as deltaic cycles–these

deposits built up the complex coastline of Louisiana. They worked in concert and in contest with the forces of oceanic erosion. However, three hundred years of levee-building upriver have increasingly deprived the delta of the sediment portion of this equation. The decrease is drastic: before 1900, the river carried an estimated 400 million metric tons of sediment per year to the delta. By the year 2000, it was carrying only 145 million metric tons per year. That’s a reduction of 64%. As a consequence, the Louisiana coast is eroding at the rate of one football field every 30 minutes. Erosion of the delta was a major contributor to the catastrophe known as Katrina.

But erosion is not the only problem we’ve unfairly blamed on the river itself. Flooding has become chronic, with major floods occurring in 1825, 1844, 1849, 1858, 1927, 1937, 1973, 1983, 1993, 2011, and 2014. Systemic breakdowns have occurred in the greatest of the floods, those in 1927, 1937, 1973, and 1993. Not surprisingly, these floods rival one another for their destruction, death toll, and costliness. Each flood has summoned greater technical solutions and increased the involvement of the Federal government. Since the Flood Control Act of 1928, the US Army Corps of Engineers has been given the prime responsibility for flood control along the Mississippi River. The Corps’ official motto is “Let Us Try.” Each time they try, they succeed in increasing the risk of greater disaster.

During the August 2005 arrival of Hurricane Katrina, the Corps’s flood protection system failed catastrophically, with levee breaches in over 50 locations. The Mississippi River-Gulf Outlet Canal, another Corps undertaking, provided an expressway for the hurricane, funneling it directly into the city. It was one of the deadliest hurricanes in US history, largely due to one of the worst civil engineering failures in US history.

The US Army Corps of Engineers have received a torrent of criticism for their approach for managing the Mississippi River and its outlet. An enlightening and somewhat startling indictment appears in the August 2007 issue of Time Magazine. Michael Grunwald’s indignation in his article “The Threatening Storm” should be our own.

In response to Katrina’s destruction, the Corps has responded as we might anticipate. The solution is not to gradually undo our repression of the river and gently wend our way, as much as is possible, to a naturally functioning system. The solution-in-progress is to build more containment, in a project that has been dubbed The Great Wall of Louisiana. Irony sizes up all those hunky points of failure and licks her lips.

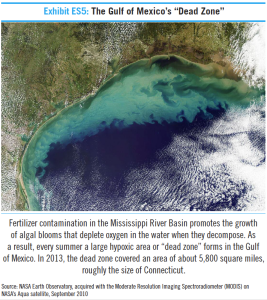

But counter to irony there are other all-too-unsurprising stories running alongside the damned Mississippi River. Being such a major thoroughfare throughout the life of America, it has served as a mirror of our nation’s progress. As industrial agriculture has spread across the US Midwest, it has also delivered a payload of toxic runoff into the Mississippi River system. This in turn has created a massive and growing dead zone in the Gulf of Mexico.

Flowing concurrently with environmental degradation is the continued deterioration of racial justice. The lower Mississippi valley has seen institutionalized enslavement of Africans transform into the Black Codes of the post-Civil War South. Land granted to Freedmen under Congressional mandate was returned to Southern whites through President Andrew Johnson’s amnesty programs. Black Americans were routinely forced into labor on levee projects throughout the latter 19th and early 20th centuries.[17] Institutionalized disenfranchisement has led to widespread urban marginalization, which factored into the racially-charged aftermath of Hurricane Katrina.

The past is often a harbinger of the future. One thousand years prior to Hernando de Soto’s Mississippi River forays, a highly advanced society flourished at the confluence of the Mississippi, Missouri, and Illinois Rivers. The Cahokia peoples established a trade network that reached from the Great Lakes to the Gulf of Mexico, employed sophisticated agricultural techniques, built lasting monuments, and controlled the manufacture and distribution of technologically-advanced tools. Central to their settlement was an imposing mound, rising to 100 feet and covering 15 acres of ground. From its summit, their kings would arrange for the weather to favor their agricultural fields.[18]

The Cahokians also had a strong urge towards deforestation and exploitation of resources. The collapse of their society in the 14th century has been credited to unsustainable agricultural practices,[19] over-hunting of the surrounding regions, and floods resulting from the landscape that they had rendered bare–and over which their kings had claimed control.[20]

“Given Cahokia’s engineering expertise,” writes Charles C. Mann in 1491, “solutions were within reach: terracing hillsides, diking rivers, even moving Cahokia. Like all too many dictators, Cahokia’s rulers focused on maintaining their hold over the people, paying little attention to external reality.”[21]

The beauty of hubris is its built-in irony: it will eventually deprive itself of the stage upon which to strut its stuff.

Our tightly integrated political and economic system resembles the Old River Control Structure, a floodgate system built in 1963 near the border of Mississippi state and Louisiana. Its purpose is to keep the Mississippi River in its current course, even though it wishes to jump over into the Atchafalaya Basin. The river has changed course many times; this is part of a river’s natural behavior. However, for the sake of economy the Mississippi is being held into place by order of the US Congress. The Army Corps of Engineers enforce these orders. However, there are weaknesses in the Old River Control Structure which almost brought it to a collapse during the 1973 flood. Our monolithic establishment also has weak points, and by working in those gaps, perhaps we can influence change or undermine repressive structures.

First, any effort we can make to eliminate our personal consumerist impulses will help. We have been bred, as Americans, to want more, get more, constantly work for more. Our desires require resources, and by decreasing our desires we can reduce industrial encroachment into our few remaining natural areas.

We can support, at the grassroots level, more natural forms of agriculture. We can withhold our support for industrial agriculture. Please visit the Organic Consumers Association online at www.organicconsumers.org.

We can work to establish food equality throughout our land of plenty. Please visit the Food Empowerment Project at www.foodispower.org.

We must create alternate economies which operate independently of industrialized institutions. Please visit YES! Magazine’s website to learn more, or read this article from Mother Earth News.

We can work to correct the long-standing social injustice which is a chief characteristic of our nation. Concurrent with the history of the Mississippi River is the development of southern slave culture, marginalization of freedmen during Reconstruction, the use of forced African American labor on late 19th-century levee projects, further disenfranchisement due to natural disasters such as flooding, and the deadly insult of Hurricane Katrina. This happens within us each as individuals, and is demonstrated in our every action, private or public. Quite simply, we must fight oppression. And continue to fight oppression. Then we should fight some more.

Our energy is needed on each issue, for they are woven together in a massive watershed. Our good actions lead to a healthy functioning social system, and support greater fertility for other good actions.

Further Reading, Heavily Recommended:

John McPhee, “Atchafalaya,” New Yorker, February 23, 1987

Michael Grunwald, “The Threatening Storm,” Time, August 2, 2007

The Rise and Disappearance of Southeast Louisiana, an interactive graphic by Dan Swenson of the New Orleans Times-Picayune, March 4, 2007

Alexis C. Madrigal, “What We’ve Done to the Mississippi River: An Explainer,” The Atlantic, May 19, 2011

Notes:

[1] Christopher Morris, Big Muddy: An Environmental History of the Mississippi and Its Peoples from Hernando de Soto to Hurricane Katrina (Oxford University Press, 2012), 169-170.

[2] Alexis C. Madrigal, “What We’ve Done to the Mississippi River: An Explainer,” The Atlantic, May 19, 2011, accessed July 22, 2015, http://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2011/05/what-weve-done-to-the-mississippi-river-an-explainer/239058/

[3] Morris, 57.

[4] Morris, 61.

[5] Morris, 95.

[6] “Levee Systems,” US Army Corps of Engineers, accessed July 22, 2015, http://www.mvd.usace.army.mil/About/MississippiRiverCommission%28MRC%29/MississippiRiverTributariesProject%28MRT%29/LeveeSystems.aspx

[7] Kurt Michael Friese, Kraig Kraft, Gary Paul Nabhan, Chasing Chiles: Hot Spots Along the Pepper Trail (Chelsea Green, 2011), 101-102.

[8] Charles Mackay, Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds (London: Richard Bentley, 1841), 1-45.

[9] Morris, 53.

[10] Mackay, 32.

[11] Morris, 54. See also the St. Charles Museum and Historical Association: http://www.historyofstcharlesparish.org/index.php/18th-century/the-french-colonial-period-1698-1762/john-laws-charter

[12] Morris, 75.

[13] Morris, 117.

[14] Mackay, 28.

[15] Morris, 65, 119, 92, 176, 145, 175, 136.

[16] Morris, 102, 122, 185, 189.

[17] Morris, 148-149.

[18] Charles C. Mann, 1491: New Revelations of the Americas Before Columbus (Vintage, 2011), 29.

[19] Morris, 21.

[20] Mann, 29.

[21] Man, 304.