A rooster crows to mark out his territory and establish dominion. If Dr. John Romulus Brinkley had been a rooster, his flock would have included every North American from the Rio Grand River to the North Pole, and even a few Soviets. Fueled by Depression-era medical quackery and inspired engineering, his XER AM radio signal roared out of Ciudad Acuña, a Mexican town just across the border from Del Rio, Texas. Locals said that its signal rattled their bedsprings, turned on car headlights, and bled into telephone conversations. Non-locals, like radio station operators in Atlanta and Montreal, condemned it for interfering with their own signals.[1]

Along with his own questionable cures–such as xenotransplantation of goat testicular cells into the genitals of presumed impotent men–Dr. Brinkley promoted his own political aspirations, fostered QVC-style infomercials, and helped propel the careers of Jimmie Rodgers, the Carter Family, and other revered pioneers of American roots music. Brinkley’s story defies condensation, touching as it does upon medical charlatanry, male insecurity, cutting edge electronic engineering, innovative advertising, landmark Supreme Court decisions, federal communications legislation, popular culture, international treaties, the birth of mass-media evangelism, and the KGB, who listened in to his signal to brush up on their English.

His story is far too wow-inducing to leave at that. I encourage you to read this highly-entertaining account here. (Another informative article is here. A film is in the works here.)

XER (and its successor XERA) operated from 1932 to 1939, existing in the shadow zone of the US-Mexico border. Dr. Brinkley, having pioneered AM radio in 1920s Kansas, built XER’s transmitter with the expressed purpose of circumventing US broadcast regulations. Mexico was eager to help him, for they also wished to get around gringo airwave limitations. They had sought a cooperative division of the airwaves across North America, hoping to broadcast to refugees of the Mexican Revolution and other immigrants scattered throughout the US. The US, however, made such peaceful coexistence difficult. In came Brinkley with a team of distinguished engineers ready to outdo themselves, and together they built the most powerful radio transmitter ever to exist upon the planet. This rooster crowed with half a million watts. Some say a full million.

The massive signal lobbed across the continent not only underground hillbilly and blues recordings but the call of mystics, faith-healers, and purveyors of autographed photos of Jesus Christ. It was full-service garage-sale America, and it made the good doctor a millionaire several times over. On the less surreal plane of terra firma, it was a grand exercise in dominion. There was a lot at stake along the border.

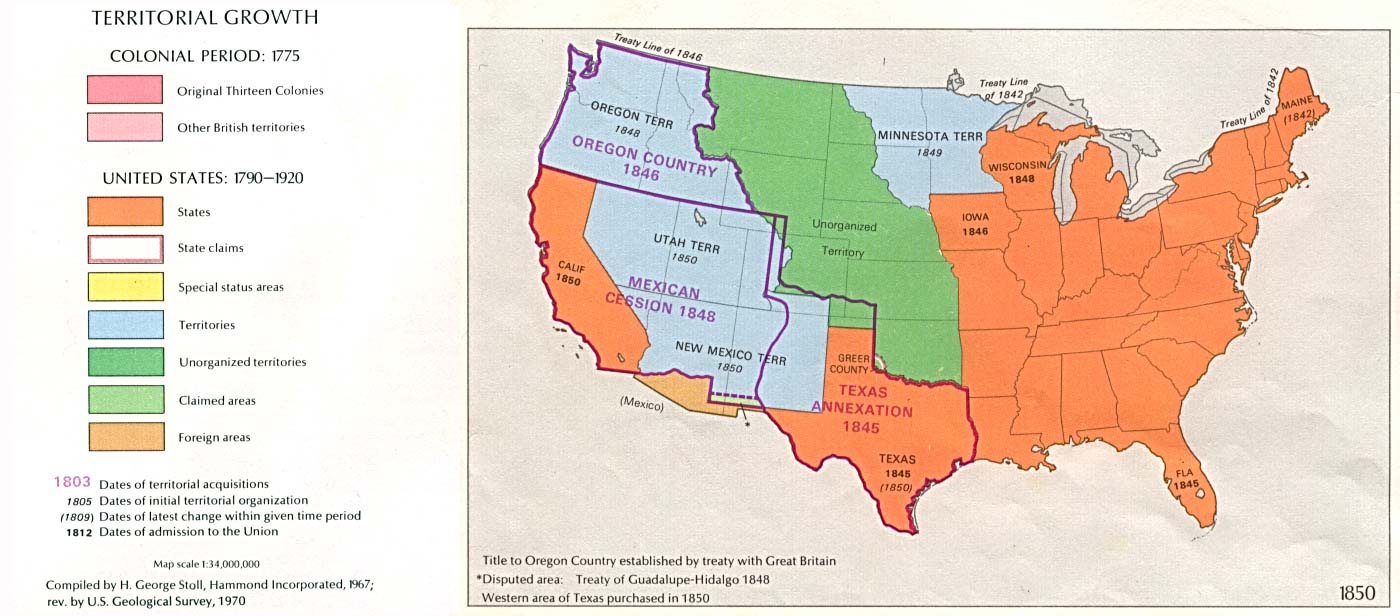

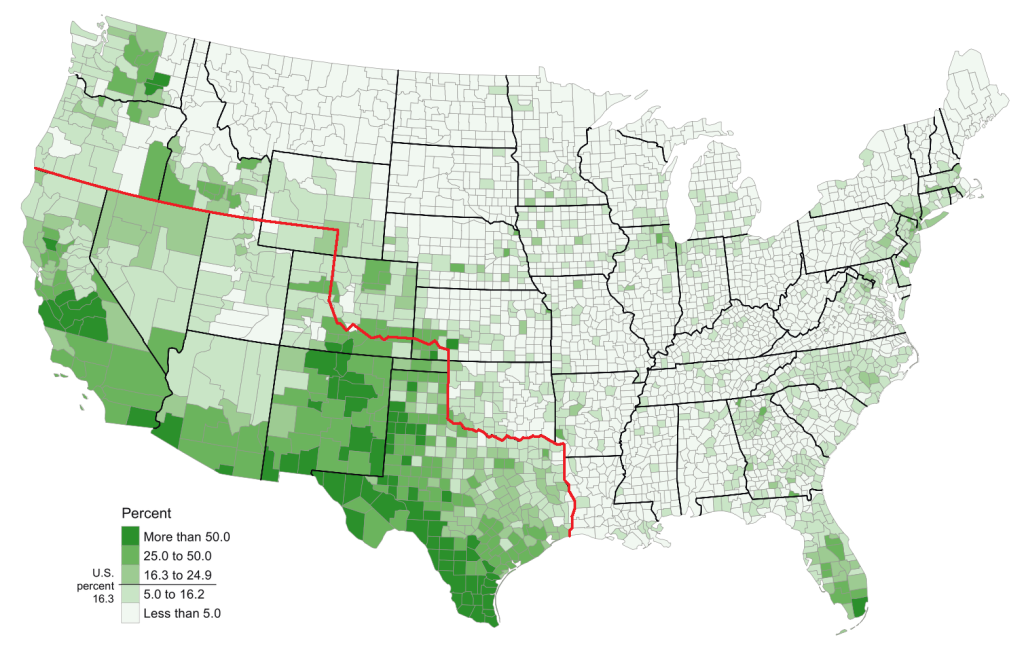

Behind the inventive ego of Dr. Brinkley lies the long and complicated history of Mexican-US relations, still working its way into an infinitely tangled knot. The questionable breakaway of Texas from Mexico in 1936 left an unofficially delineated border and an unsanctioned treaty. The annexation of Texas by the United States in 1845 was followed by US military trespass into Mexico. At the end of the resulting war, Mexico ceded over half of its territory to the United States, currently known as California, Nevada, Utah, New Mexico, most of Arizona and Colorado, and parts of Texas, Oklahoma, Kansas, and Wyoming. By 1848, the dream of American Manifest Destiny was realized: the United States had extended its dominion to the Pacific Ocean.

The decades between the cession of Mexican lands and the advent of Dr. Brinkley were not peaceful ones. Mexico and other Latin American countries were in frequent political turmoil, some of it due to internal forces, some to external forces. The US intervened heavily, sometimes under the guise of the Monroe Doctrine or under cover of the (Theodore) Roosevelt Corollary. In 1933, President Franklin Roosevelt instituted his Good Neighbor foreign policy in an attempt to improve pan-American relations. His goal wasn’t entirely altruistic: he believed that adopting a more friendly demeanor towards Latin America would result in more economic opportunity, which is, after all, the impetus behind all American activity. After decades of US aggression, it is hard to imagine anyone taking his crow seriously.

Superficialities, however, came out of the woodwork. Radio was alive with the sounds of happy neighbors, as hosts played records from Latin American artists, linguists explained Spanish to English-only listeners, and dignitaries presented travel adventures. Concerts, films, and other cultural exchanges illustrated that to be pan-American-minded was to be a good American.[2]

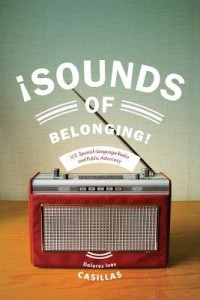

However, Mexicans living in the US were not included in the neighborly programs. In fact, public opinion was further turned against them. Dolores Inés Casillas, Associate Professor of Chicana and Chicano Studies at the University of California, Santa Barbara, writes, “American-sponsored [radio] programming peddled themes of hemispheric unity, despite the prevailing nativist attitudes, separating domestic and international agendas. American listeners developed imaginary friendships with Mexicans over there, whereas Mexican communities living here were depicted as unruly neighbors.”[3] Anti-Mexican sentiment was nothing new, having been fomented as propaganda before the Mexican-American War. Heavily racialized speeches filled Congress and the newspapers, with calls for “white destiny” to be fulfilled.[4]

Behind the glittery veneer of Rooseveltian neighborliness, the US issued constant requests to Mexico for laborers. Those who came were outfitted with short hoes and short paychecks. The Mexican “immigration problem” received frequent play in the press.[5] We might have changed our lyrics, but our song remained the same.

One song captures the moment well: “South of the border/Down Mexico way/That’s where I fell in love/When stars above/Came out to play,” begins a popular song from 1939, sung first by XERA veteran Gene Autry. The song’s superficial story is a romantic one: an American cowboy ventures into Mexico and has a one-night stand with a Mexican woman: “it was Fiesta, and love had its day,” he explains somewhat cavalierly. She asks about meeting again mañana, and he agrees. But alas, he has lied, knowing that he will return to the States instead. Some time later, he drifts south to find her praying at an altar, mission bells resounding overhead. There is sufficient ambiguity to wonder if she is in a convent or at her own wedding. Either way, he leaves again without saying “buenos dias.” The tale is one-sided, of course. She isn’t given a voice.

Though long-canonized as an American Standard, it isn’t really a romantic ballad at all. It is a glamorized account of American conquest in Mexico. It is the sound of the filibuster: in the 1800s, several American adventurers obligated themselves to overthrowing Latin American governments and establishing themselves as dictators. The term has since been used to describe a parliamentary procedure wherein a speaker will not yield the floor to a dissenting opinion. The song South of the Border, like the Congressional filibuster, is the sound of Anglo-American dominance.

Sound-as-dominion is an obsession of the online publication Sounding Out!, a highly academic and dynamic venue for scholars, artists, and readers “interested in the cultural politics of sound and listening.” In a currently ongoing series, they are reviewing a project from the 1960s and 70s, wherein a team of recordists set out to capture what Canada sounded like.

Writer Mitchell Akiyama explains that “a ‘soundmark’ is roughly analogous to a landmark: it’s a sound that is supposedly instantly recognizable to members of a community, an irreplaceable acoustic feature of a particular place.” He quotes a member of the original project’s team: “It takes time for a sound to take on rich, symbolic character—a lifetime perhaps, or even centuries. This is why soundmarks should not be tampered with carelessly. Change the soundmarks of a culture and you erase its history and mythology. Myths take many forms. Sounds have a mythology, too. Without a mythology, a culture dies.”

Tampering happens at all levels of our society, from government chambers to the most common workplaces–such as restaurant kitchens. Routinely staffed by Mexican immigrants, they are filled with the sound of Spanish. It is the soundmark of a kitchen.

When I was employed at a prominent raw food cafe and school in Ft. Bragg, CA, management sent down the decree: no more Spanish was to be spoken in the kitchen. My Mexican colleagues and I noted that the decree did not prohibit singing in Spanish. A request for the peeler or the blender or even a toothpick instantly became a song. We soon tired of our own mischief, but the point was made: the soundmark will remain, regardless of biased mandates.

Subversive behavior aside, a soundmark has a purpose. It is the sound of “home,” and is invaluable to a culture that has become scattered across the continent. Casillas states, “Spanish-language broadcasts along the West Coast have long provided nationalist sustenance for a Mexican-dominant listenership that is yearning for an audible, familiar semblance of ‘home.'” Experiencing physical and emotional displacement is common among immigrants. To hear one’s language is to find a stabilizing touchstone. Home is not just a fixed, physical place, but “a mobile symbolic habitat, a performative way of life and of doing things in which one makes one’s home while in movement.”[6]

In every kitchen I’ve entered, I have listened for the sounds of Spanish-language radio. Its existence is an indicator of the health of the kitchen. It speaks of community, strength, family, solidarity, and progress. It also speaks volumes about management.

But not all see it as a positive. To some, all that Spanish-speaking provokes suspicion and fear, and fuels a rising tide of anti-immigrant sentiment and violence.

Writes Jennifer Stoever, Editor-in-Chief of Sounding Out!, regarding Arizona’s anti-immigration SB-1070: “Because unspoken, racialized norms about sound exist and circulate through American culture via the listening ear, members of dominant groups may use sound with impunity to forge ‘reasonable suspicion’ about the citizenship status of anyone who sounds different from them (and who creates, consumes, and appreciates sounds differently from them). Certainly the sound of Spanish is at the top of this list.”[7]

In other words, “You don’t sound American. You got any papers?”

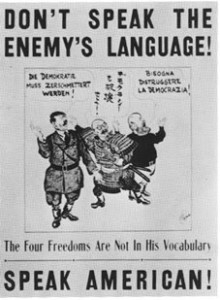

Silencing non-English language has been an American pastime over the past 100 years or so. German-language materials were forbidden during the World War I; bilingual education has been banned in various states; Native American children have been enrolled in English-only boarding schools to remove them from their language; and the radio waves have been routinely and bureaucratically cleared of all polyglot tendencies.[8]

But what does America actually sound like? White residents of Arizona? Polyrhythmic multilingual Manhattan? Kentucky bluegrass played on an African instrument? The United States is the second-largest Spanish speaking country in the world.[9] Whatever America actually sounds like, it is not monolingual by any means.

Our fixation on English-only society is sometimes passive and selective, rather than violent or legislative. Once again Mitchell Akiyama, regarding the recording of the “what Canada sounds like” project: “It should also go without saying that the soundmarks they so prized were deeply entangled with a silencing of Canada’s indigenous population; of a protracted, often violent and brutal, campaign of assimilation that replaced one set of sonic practices with another.”[10]

There is a response to all this suppression: the suppressed step over the line and build the most powerful radio in the world. Dr. John R. Brinkley was on the outs with US authorities when he built the first border blaster. By agreement with the Mexican government, one quarter of his programming was in Spanish. Mexico found a way to reach its dispersed people.

Today, Spanish-language radio continues its public mission in spite of the changes in dominant listening methods. Writes Casillas in a Sounding Out! essay: “The very public nature of Spanish-language radio listening represents a communal, classed, and brown form of listening that differs markedly from ‘white collar’ modes of listening, which offers more solitary practices, promoted by commuting in private cars and listening to personal satellite radios, iPods, or Internet broadcasts.

“For instance, one can routinely overhear loud Spanish-language broadcasts from the back kitchens of restaurants (regardless of the ethnic cuisine); outside bustling construction sites and Home Depot storefronts as day laborers await work; or from small radio sets balanced heroically on hotel housekeeping carts. On-air salutations heard throughout the day on Spanish-language radio are vocal nods to worksites as radio hosts greet washeros (car wash personnel), mecánicos (mechanics), fruteros and tamaleras (fruit and tamale street vendors), and those, presumably farmworkers, toiling under the sun.”

“Listening loudly in the face of anti-immigrant public sentiment,” she continues, “becomes a form of radical self-love, a sonic eff-you, and a means of taking up uninvited (white) space.”[11]

Spanish-language programming did exist in the US prior to XERA’s reign of power. In the 1920s, English-language stations sold their most undesirable timeslots to Spanish producers such as Pedro J. Gonzalez, whose early-morning shows greeted campesinos as they prepared to go to the fields. When local and national regulations threatened to silence them, they partook of Dr. Brinkley’s miracle cure for FCC interference and moved across the border.[12] As Brinkley and Roosevelt were furthering their empires, Mexicans–here and in Mexico–were trying to learn how to live in them.

But they were not seeking economic or political advantage, as were the good doctor and the president’s foreign policy mavens. The operators of Spanish-language radio were doing then what they are still doing now: broadcasting “home” to their wandering compadres, working to unify, educate, and inform them. Helping them learn to live as immigrants in a country that is far too hostile towards its neighbors, yet mysteriously filled with sonorous Spanish place-names: California, Nevada, Arizona, Colorado; San Diego, Los Angeles, Santa Fe, San Antonio.

Just as Spanish-language border radio shot over US resistance, community radio lay below the mainstream. The first bilingual non-commercial radio station in the US, KBBF-FM (Santa Rose, CA), went on the air in 1973. Its mission was clear: “To create a strong multilingual voice that empowers and engages the community to achieve social justice through education, celebration of culture and local and international news coverage.” Born amidst the Chicano Movement, its purpose is relevant to all, regardless of origin, language, or heritage. It is a very American mission.

As Casillas relates, KBBF and its fellow bilingual stations have resumed the practice of those 1920s Spanish-language radio pioneers, providing much needed information and influence, promoting literacy, sobriety, and good citizenship. And as commercial Spanish-language radio has grown–by 1995, it dominated Los Angeles, San Antonio, Miami, and New York–it too has continued the tradition. National call-in shows help listeners navigate the complicated US citizenship process, give advice regarding medical and legal rights, offer ESL assistance, help with H-2A compliance, and provide drivers’ education. The focus is on improvement and the preservation of cultural identity–far more beneficial than the consumption-driven message of Dr. Brinkley.[13]

Immigrants are indeed navigating a tsunami of US consumer-based identity. They are not alone in this, for our northern neighbor struggles with the pervasive US personality. “The history of the Canadian airwaves is profoundly mired in struggles to promote, produce, and foster content that might keep the national identity from being completely subsumed under the sprawl and heft of the American culture industry.”[14]

The American culture industry is not, however, in danger of being subsumed under anyone. Its only risk is self-induced: it might one day be eliminated by its own noise, much like Londoners. De nobis fabula narrabitur.

Speaking of noise, I need to clarify my statements about roosters. It is true that they mark their domain by crowing. But they also crow to communicate with other roosters, to check in and see that all is well. Roosters are perfectly capable of sharing space, as they do at VINE Sanctuary in Vermont. Even those trained to fight to the death can learn to live in peace.

Our Menu

The cuisine of the US-Mexico borderlands is a bold, multi-lingual synthesis of methods, foods, and attitudes from native North America, old Spain, and the westward push of the US. The border is not its boundary; rather, the border is its central, invisible highway. This menu reflects shared heritage, coexistence, and the beauty of intercultural understanding: a peaceful contrast to all the aggressive crowing. The dessert highlights our northern border: the longest undefended border in the world.

What We Can Do:

Learn

Listen

Read

Progress

Get your news from a non-commercial source:

http://democracynow.org/

http://www.pacifica.org/

http://www.ecodefenseradio.org/

Support community radio, or consider starting a station: http://prometheusradio.org/stationprofiles

Listen to XERF, the offspring of Dr. Brinkley’s original border station. It continues its high-wattage broadcasts of Mexican immigrant identity.

And the gratuitous yet thoroughly justified inclusion:

Notes:

[1] Pope Brock, Charlatan: America’s Most Dangerous Huckster, the Man Who Pursued Him, and the Age of Flimflam (Crown, 2008), 35.

[2] Dolores Inés Casillas, Sounds of Belonging: U.S. Spanish-Language Radio and Public Advocacy (New York University Press, 2014), 14.

[3] Casillas, 23.

[4] Howard Zinn, A People’s History of the United States, (Harper Perennial Modern Classics, 2005), 149-169.

[5] Casillas,22.

[6] Casillas, 5.

[7] Jennifer Lynn Stoever, “The Noise of SB 1070: or Do I Sound Illegal to You?,” Sounding Out!, August 19, 2010, accessed September 22, 2015, http://soundstudiesblog.com/2010/08/19/the-noise-of-sb-1070/.

[8] Phillip M. Carter, “Why this bilingual education ban should have repealed long ago,” CNN, March 4, 2014, accessed September 22, 2015, http://www.cnn.com/2014/03/04/opinion/carter-bilingual-education/; see also https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/English-only_movement

[9] Stephen Burgen, “US now has more Spanish speakers than Spain – only Mexico has more,” The Guardian, June 29, 2015, accessed September 22, 2015, http://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2015/jun/29/us-second-biggest-spanish-speaking-country?CMP=share_btn_tw

[10] Mitchell Akiyama, “Unsettling the World Soundscape Project: Soundscapes of Canada and the Politics of Self-Recognition,” Sounding Out!, August 20, 2015, accessed September 22, 2015, http://soundstudiesblog.com/2015/08/20/unsettling-the-world-soundscape-project-soundscapes-of-canada-and-the-politics-of-self-recognition/.

[11] Dolores Inés Casillas, “Listening (Loudly) to Spanish-Language Radio,” Sounding Out!, July 20, 2015, accessed September 22, 2015, http://soundstudiesblog.com/2015/07/20/listening-loudly-to-spanish-language-radio/.

[12] Casillas, 40.

[13] Casillas, 23, 76, 86.

[14] Akiyama, “Unsettling the World Soundscape Project: Soundscapes of Canada and the Politics of Self-Recognition,”