Peace Meal Supper Club™ #17.5: Sanctuary is an exploration of identity and definition. From our privileged vantage point, how does the present-day struggle of Syrian refugees look? Do we see a reflection of Central American refugees, who fled civil war in the 1980s? When we remember the Underground Railroad of the 1800s, which carried over 100,000 US slaves to freedom, can we project its success forward, envisioning sanctuary for all? And most importantly, how do we see ourselves in the midst of such unrest?

Do we see ourselves as human, beyond all limited identifiers? Or do national, religious, social, political, philosophical, and racial definitions fragment our humanity?

In a recently discovered recording from December 7, 1964, Martin Luther King, Jr., declares: “The basic thing about a man is not his specificity, but his fundamentum, not the texture of his hair or the color of his skin, but his eternal dignity and worth…Fleecy locks, and black complexion cannot forfeit nature’s claim; Skin may differ, but affection dwells in black and white the same…were I so tall as to reach the pole, or to grasp the ocean at a span, I must be measured by my soul; the mind is the standard of the man.”

This transcendence of externalities is the living heart of human progress. It’s a golden cord which not only binds us spiritually, but leads us along the arc of the moral universe. It is firmly knotted in Utopia.

Our sublimely human identity has given us Eden’s Garden, Paradise, the Peach Blossom Spring, Shambhala, Avalon, and dreams of the Peaceable Kingdom. This unified pursuit of utopia persistently offers us the most beautiful position: peace, freedom of expression and person, and expansion of humaneness to always include others. But fragmented identities, by nature, are insecure. They fight aggressively for dominance under the banners of superiority, manifest destiny, and imperialism.

Thankfully, humanity’s indomitable spirit urges us to find the means—however subversive, ingenious, and resourceful—to extend hands of compassion. We have set our milestones in global forums, and offered our assent to a canon of international expressions.

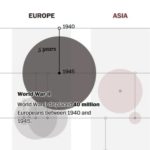

For example, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which the United Nations adopted in 1948. A response to the horrific experiences of World War II, the declaration established specific rights due to all individuals. It strengthened the goal upon which the UN was founded, that of “universal respect for, and observance of, human rights and fundamental freedoms for all without distinction as to race, sex, language, or religion.”

As refugees of World War II sought safe haven, the UN shepherded the 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees, which declared the rights of people who have been forced out of their homes and homelands by war or other threats. It upheld the duty of all nations to assist. This multilateral document was followed in 1967 by the Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees, which further elaborated the aid due anyone fleeing strife in their homelands. Signatories, which included the United States, bound themselves by international law to provide refuge to anyone fleeing violence at home.

These modern statements connected us with practices in our shared past. Greece, Egypt, medieval England, and the Jews of the Old Testament all took care to take care of the troubled stranger. Their compassion reached over all conflicts to help the innocent victims, declaring that the powerful do indeed have an obligation to the powerless. As we enter 2017, that obligation is larger than it has ever been, for “an unprecedented 65.3 million people around the world have been forced from home. Among them are nearly 21.3 million refugees, over half of whom are under the age of 18.”

Who exactly is a refugee? According to the 1951 Convention and the 1967 Protocol, a refugee is a person who “owing to well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion, is outside the country of his nationality and is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to avail himself of the protection of that country; or who, not having a nationality and being outside the country of his former habitual residence as a result of such events, is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to return to it.”[1]

Who exactly is a refugee? According to the 1951 Convention and the 1967 Protocol, a refugee is a person who “owing to well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion, is outside the country of his nationality and is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to avail himself of the protection of that country; or who, not having a nationality and being outside the country of his former habitual residence as a result of such events, is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to return to it.”[1]

Many nations are offering safe haven to the world’s displaced, such as Turkey, Lebanon, Jordan, Iraq and Egypt. Together, they have taken in 4.8 million Syrian refugees. The United States admitted 10,000 Syrian refugees in 2016, increasing its offers of residency only after being pressured by other nations. But refugees are fleeing wars in other countries, as well: Afghanistan, Somalia, Sudan, Yemen, Colombia, and many more. US involvement in global warfare—currently the US is involved in five acknowledged wars and 134 covert ones—greatly overshadows its limited humanitarian aid. It’s enough to make any US citizen wonder about their national, if not personal, identity.

Nationally, it’s complicated terrain, having been an ideological battlefield for generations. But visiting a crisis in our not-so-distant past can help us find a starting place. Its point of origin was Central America’s Northern Triangle—comprising El Salvador, Honduras, and Guatemala—where the US military first became involved in 1901. What began as militarily-aided corporate takeover of Honduras by American fruit companies evolved into a series of overthrows backed by Eisenhower and led by the CIA. The conflicts escalated in the late 1970s, and by the 1980s the US was arming and financing civil war in El Salvador. This civil war displaced over a million civilians, many of whom fled to the southern US border seeking asylum.

Nationally, it’s complicated terrain, having been an ideological battlefield for generations. But visiting a crisis in our not-so-distant past can help us find a starting place. Its point of origin was Central America’s Northern Triangle—comprising El Salvador, Honduras, and Guatemala—where the US military first became involved in 1901. What began as militarily-aided corporate takeover of Honduras by American fruit companies evolved into a series of overthrows backed by Eisenhower and led by the CIA. The conflicts escalated in the late 1970s, and by the 1980s the US was arming and financing civil war in El Salvador. This civil war displaced over a million civilians, many of whom fled to the southern US border seeking asylum.

The US Congress, during the final months of the Carter Administration, passed the Refugee Act of 1980, intending to “provide for the effective resettlement of refugees and to assist them to achieve economic self-sufficiency as quickly as possible after arrival in the United States.” The incoming Reagan Administration viewed things differently, however, and labeled the asylum-seekers as economic opportunists and criminals.[2]

In humanitarian response, private citizens opened their doors, and the Sanctuary Movement was born. The Migration Policy Institute (MPI) summarizes its development: “The network of religious congregations that became known as the Sanctuary Movement started with a Presbyterian church and a Quaker meeting in Tucson, Arizona. These two congregations began legal and humanitarian assistance to Salvadoran and Guatemalan refugees in 1980…When, after two years, none of the refugees they assisted had been granted political asylum, Rev. John Fife of Southside Presbyterian Church in Tucson announced—on the anniversary of the assassination of Salvadoran Archbishop Óscar Romero—that his church would openly defy INS and become a ‘sanctuary’ for Central Americans. The Arizona congregations were soon joined by networks of religious congregations and activists in Northern California, South Texas, and Chicago.”

While in sanctuary, Salvadoran refugees hoped for freedom from harassment due to ethnicity, faith, and gender. They often needed access to medical facilities and legal channels. Mostly, they needed a safe place to wait out the strife at home—which is where they intended to return. They brought with them their stories, of course. As their stories became public, the US Department of Justice responded by initiating criminal prosecutions against two activists in Texas in 1984. This was followed by a 71-count criminal conspiracy indictment against 16 U.S. and Mexican religious activists announced in Arizona in January 1985.

“Salvadorans and Guatemalans arrested near the Mexico-U.S. border were herded into crowded detention centers and pressured to agree to ‘voluntarily return’ to their countries of origin. Thousands were deported without ever having the opportunity to receive legal advice or be informed of the possibility of applying for refugee status,” relates MPI. These deportations were a clear violation of the 1951 Refugee Convention.

The reasons for the expulsions soon became apparent. During the Texas trials, US District Judge Earl Carroll barred the defense from mentioning the violent conditions in El Salvador. He knew that to allow such testimony would not only validate the refugees’ status according to international law, it would also expose the violent role the US played in creating the refugees in the first place.

The Sanctuary Movement, in granting venue to the refugees’ stories, fundamentally challenged our view of ourselves. Refugee activists aligned the Sanctuary Movement with other civil rights movements, thereby challenging “not just one immigration law, but a whole pattern of exploitation,” writes Robin Lorentzen in Women in the Sanctuary Movement.[3]

Today, in delivering their news of war, refugees once again cause us to question who we are. For some of us, it is confirming: we are compassionate people, seeking to help those in need. For others, it can be unsettling, and lead to questions of personal and national identity. Some resist the questions altogether, and suppress the impulse to answer them.

Individuals and institutions might struggle with fragmented identities, but transcendent humanity finds its expression. When we, the people, lead with our humanity, we are very good at providing sanctuary—just as we did in the 1940s when 40 million Europeans were displaced. We also performed admirably as our own civil war was raging: the Underground Railroad carried over 100,000 people to safety in the northern US and Canada, in defiance of federal law.

But at times we, as a nation, lead with our politics. Consider, for example, these words from US Senator Pat McCarran of Nevada: “I believe that this nation is the last hope of Western civilization and if this oasis of the world shall be overrun, perverted, contaminated or destroyed, then the last flickering light of humanity will be extinguished. I take no issue with those who would praise the contributions which have been made to our society by people of many races, of varied creeds and colors. However, we have in the United States today hard-core, indigestible blocs which have not become integrated into the American way of life, but which, on the contrary are its deadly enemies. Today, as never before, untold millions are storming our gates for admission and those gates are cracking under the strain. The solution of the problems of Europe and Asia will not come through a transplanting of those problems en masse to the United States.”

But at times we, as a nation, lead with our politics. Consider, for example, these words from US Senator Pat McCarran of Nevada: “I believe that this nation is the last hope of Western civilization and if this oasis of the world shall be overrun, perverted, contaminated or destroyed, then the last flickering light of humanity will be extinguished. I take no issue with those who would praise the contributions which have been made to our society by people of many races, of varied creeds and colors. However, we have in the United States today hard-core, indigestible blocs which have not become integrated into the American way of life, but which, on the contrary are its deadly enemies. Today, as never before, untold millions are storming our gates for admission and those gates are cracking under the strain. The solution of the problems of Europe and Asia will not come through a transplanting of those problems en masse to the United States.”

McCarran spoke these words in 1953, in defense of the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952, of which he was co-sponsor. His rhetoric sounds shockingly contemporary.

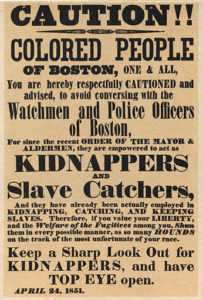

McCarren’s act aligned with other expressions of broken identity, such as the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 and President Obama’s massive deportation exercises in 2015 and 2016, in which 2.5 million people were deported. In fact, no President in US history deported more people than Obama.

As a contrast, refugee activists of the 1980s embraced our rich, multicultural heritage of providing haven. During the trials in Texas and Arizona, they cited “the Nuremberg principles of personal accountability developed in the post-World War II Nazi tribunals, [and] claimed a legal precedent to justify their violation of U.S. laws against alien smuggling. Other activists claimed that their actions were justified by the religious and moral principles of the 19th-century U.S. abolitionist movement, referring to their activities as a new Underground Railroad. Many U.S. religious leaders involved in the Sanctuary Movement had prior experience in the 1960s civil disobedience campaigns against racial segregation in the American South.”

While McCarran, Obama, and Trump speak of refugees in disparaging terms—rapists, welfare-seekers, gang members, terrorists—others of us see people like ourselves who are fleeing wars funded, armed, and executed by our government. We cannot conscientiously turn them away.

The act of turning away an asylum-seeker is also addressed in our canon of rights documents. As the UN High Commissioner for Refugees states: “The most essential component of refugee status and of asylum is protection against return to a country where a person has reason to fear persecution.”

Escaped African American slaves, when they reached the free northern states or Canada via the Underground Railroad, hoped to stay in those free lands until the conflict was resolved. European refugees during the 1940s—of which there were 40 million—hoped for the same. And the 65 million displaced people in 2017 also carry this hope of finding a safe place to wait out the wars and oppression in their homelands.

Escaped African American slaves, when they reached the free northern states or Canada via the Underground Railroad, hoped to stay in those free lands until the conflict was resolved. European refugees during the 1940s—of which there were 40 million—hoped for the same. And the 65 million displaced people in 2017 also carry this hope of finding a safe place to wait out the wars and oppression in their homelands.

The language has been clear since 1951: “No Contracting State shall expel or return a refugee in any manner whatsoever to the frontiers of territories where his life or freedom would be threatened on account of his race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion.”

This principle, known as non-refoulement has become so widely accepted that even non-member states—those not part of the United Nations, Organization of American States, Organization of African Unity, or other global organizations—readily honor it.

There is one—and only one—exception to non-refoulement. It’s this, found in Article 33(2) of the 1951 Convention: “The benefit of the present provision may not however be claimed by a refugee whom there are reasonable grounds for regarding as a danger to the security of the country in which he is, or who, having been convicted by a final judgment of a particularly serious crime, constitutes a danger to the community of that country.”

This exception, while carrying in its wording a rational approach, is too easily distorted by fear. It allows suspicion, based on a few rather than the whole, to override our humanity. And it establishes an erroneous assumption that refugees are here illegally and seek to do us harm. Perhaps the harm they do is contained in the truths they bring?

With the state of wars in the Middle East, Africa, and yes, still in Central America, refoulement is as unconscionable as sending Jews back into Hitler’s Germany. It’s as horrific as sending escaped African slaves back into Dixie. Now, as in those past ordeals, the US acts behind a curtain of national security. Today’s massive refugee detention centers summon images of the not-so-distant past, as the US relocated Japanese, German, and Italian Americans into internment camps.

Since I quoted Senator McCarran above, I should give equal time to his opponent on the 1952 Immigration and Nationality Act. President Harry S. Truman sought to veto the Act, saying, “Today, we are ‘protecting’ ourselves as we were in 1924, against being flooded by immigrants from Eastern Europe. This is fantastic…We do not need to be protected against immigrants from these countries–on the contrary we want to stretch out a helping hand, to save those who have managed to flee into Western Europe, to succor those who are brave enough to escape from barbarism, to welcome and restore them against the day when their countries will, as we hope, be free again.”

Truman was hardly a hippie peacenik, but he understood our moral responsibility. Quakers, liberation theologians, radical left Catholics, Nobel laureates, and plenty of us rational atheists have pursued paths of compassionate dissent, transforming civil disobedience into civil initiative.[4]

The more beautiful option, interestingly enough, is also the most rational: as we cease hostilities—and therefore the production of refugees—we can better assist the diminishing number who would require sanctuary. It’s a lighter burden for everyone. The ultimate solution will indeed be complicated, but we mustn’t delay pursuing peace because it’s hard.

Thankfully, in every conflict there are individuals who are inspired by our greater humanity, even when institutions falter, interfere, and forbid. They work in the spirit of Thoreau, who succinctly and eloquently proposed that “they are lovers of law and order who uphold the law when the government breaks it.”[5]

Or, as present-day immigrant activist Rabbi Linda Holtzman declares, “It is very clear in my community that when we see an unjust law it needs to be disobeyed.”

It’s a tug of war, to put it in combative terms. The progressive end of the rope is firmly anchored in the best of all possible identities. Even if we can’t see the end of it, we can work our way there.

American abolitionist Theodore Parker inspired more than one activist when he said, in 1852: “I do not pretend to understand the moral universe; the arc is a long one, my eye reaches but little ways; I cannot calculate the curve and complete the figure by the experience of sight; I can divine it by conscience. And from what I see I am sure it bends towards justice.”

What can we do?

Work for the Right to Refuse to Kill

Support modern invocations of the Sanctuary Movement:

Every Campus a Refuge

Tikkun Olam Chavurah

Not One More Deportation

Learn more about human rights, personal experiences, and the imperatives of survival:

International Rescue Committee

Human Rights Watch’s Refugee Rights Program

Center for Immigration Studies’ Sanctuary City Maps

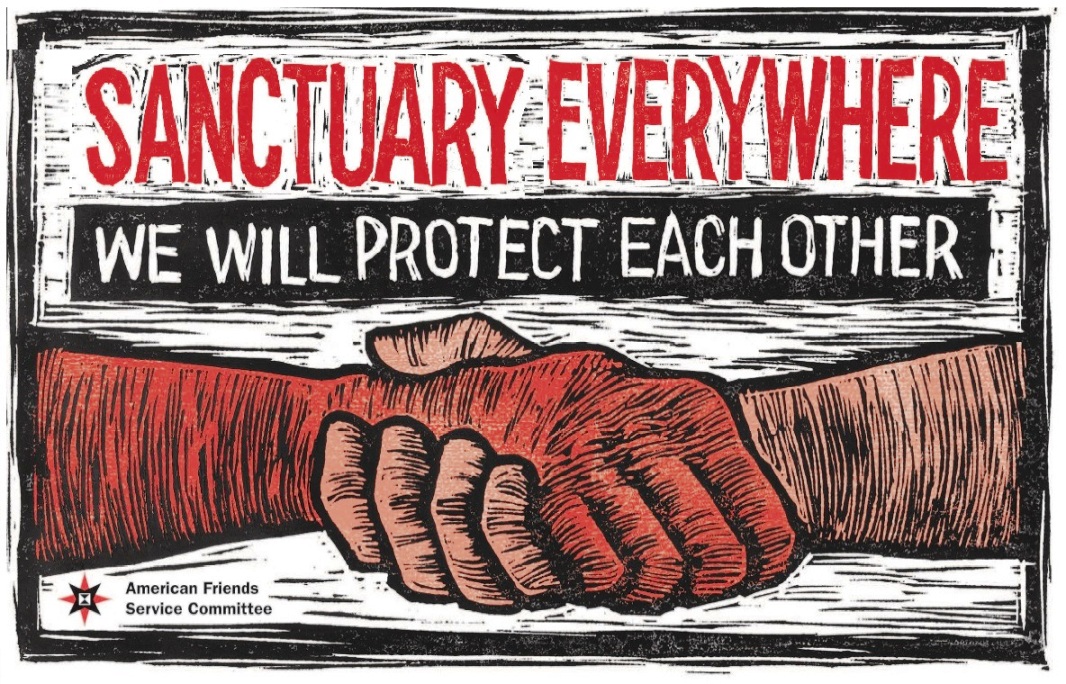

American Friends Service Committee “Sanctuary Everywhere” program

Five Facts about Migration from the Northern Triangle

NY Times: Refugee Crisis is Not an Immigration Crisis

“The Imperatives of Survival” 1974 Nobel Lecture by Sean MacBride

And this half-hour PBS segment from Peter Krogh is very enlightening if you have the time.

[1] http://www.unhcr.org/protect/PROTECTION/3b66c2aa10.pdf (will launch a PDF)

[2] Miriam Davidson, Convictions of the Heart: Jim Corbett and the Sanctuary Movement, (University of Arizona Press, 1988), 99.

[3] Robin Lorentzen, Women in the Sanctuary Movement, (Temple University Press, 1991), 24.

[4] Davidson, 80.

[5] Davidson, 80.