”That stranger, as the ghost that shadows every discourse, is the disturbing interrogation, the estrangement, that potentially exists within us all. It is a presence that persists, that cannot be effaced, that draws me out of myself towards another. It is the insistence of the other face that charges my obligation to that ‘strangeness that cannot be suppressed, which means that it is my obligation that cannot be effaced’.”—From Migrancy, Culture, Identity, by Iain Chambers.

What if that ghost, that stranger, looks back at us from a photograph? Does their insistence lose its urgency? Are we still drawn towards them, or do we turn away from the interrogation their presence demands?

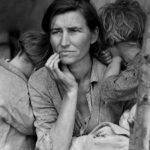

With a passion for reform, a corps of American photographers set out in 1935 to frame the insistent faces of America’s rural poor. Their photographs have come to encapsulate the Depression for many of us, as well as the accompanying ecological collapse and the subsequent displacement of thousands of families. Through skillful composition and informed selection, they documented rapidly vanishing lives and devastated landscapes.

Working in support of Roosevelt’s New Deal agenda, the photographers of the Farm Security Administration—including Dorothea Lange, Walker Evans, and Arthur Rothstein—hoped to improve conditions for poor farmers and sharecroppers who were further impoverished by the economic depression. Their cameras served as tools to “visualize social facts, to show the truth of what was happening,” unobscured by politics or fantasy.[1]

Their photos of tenant farmers, migrant agricultural workers, families, and children were printed in popular magazines, artistic journals, and news periodicals, as well as displayed in NY galleries. Public response ranged from criticism of the photos’ subjects—dirty children, salacious women, people responsible for their own poverty—to technical assessment of the photographers’ skill sets and aperture choices. The actual people, still struggling to cope with devastation, ceased to exist, having become only objects in the public’s eyes. Their very real and immediate plight had been obscured by spectacle and taste.[2]

Nascent mass culture magazines such as LOOK fostered a “stance of surveillance” on the part of the viewer, sandwiching the displaced sharecropper between a Zulu wedding pictorial and a spread of Myrna Loy in a flower-filled bathtub. “Within LOOK’s editorial vision, however, there is no cognitive dissonance here. The ‘savage,’ the sharecropper, and the sexy starlet all merit equal representation and treatment.”[3]

As Cara A. Finnegan notes in her book, Picturing Poverty, the FSA photographers faced a challenge in presenting the poor to the unpoor. “It is important to note the paradox of documentary: It purports to offer ‘real’ and ‘natural’ views of the world but is able to do so only through the framing and construction of those views.”[4] Even the most carefully constructed view can succumb to objectification.

Far from being the ‘other,’ the ‘stranger,’ or an unfortunate alternate ‘us,’ the poor had to live through the economic and environmental collapse in the most resourceful and resilient way they could manage. Programs created under the FDR administration helped considerably, but not entirely. Those programs, established to manage a temporary situation—such as the somewhat handily defined Great Depression—did not provide a permanent solution to poverty.

The poor remained well after the economic recovery brought by World War II, so President Lyndon Johnson envisioned another war. In his State of the Union Address of January 8, 1964, he pronounced:

“This administration today, here and now, declares unconditional war on poverty in America.”[5]

“Our aim is not only to relieve the symptom of poverty, but to cure it and, above all, to prevent it,” he continued. His far-reaching program focused on “a fast-growing, full employment economy; an all-out ‘assault’ on discrimination; investments in education, job training, and health care; and locally organized programs of community action, planned with what would only later be added as a legislative mandate for ‘maximum feasible participation’ of the poor.”[6]

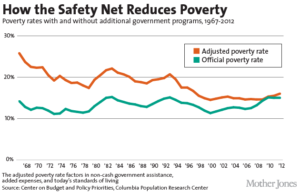

How did Johnson’s program perform? As it neared its 50th anniversary, analysts across the political spectrum weighed in. (This report in Mother Jones is particularly informative.)

Regardless of how the program performed in relieving poverty, it did not at all cure or prevent it. Neither did it cure nor prevent the objectification of the poor themselves. Through the aperture of institutional analysis, the poor have become data objects, their faces exchanged for acronyms and categories, devoid of environmental context.

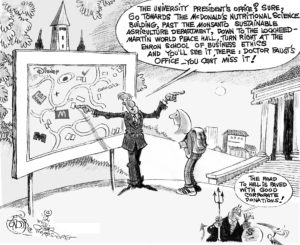

As University of California, Santa Barbara, Professor Alice O’Connor explains in Poverty Knowledge, “the technical jargon of recent decades has taken poverty knowledge to a level of abstraction and exclusivity that it had not known before. It is a language laced with acronyms that themselves speak of particular data sets, policies, and analytic techniques…in which individuals are the units of analysis and markets the principal arbiters of human exchange.”[7]

O’Connor writes about the enduring tension of federal policy, in which some view poverty as a cultural pathology, while others view it as the product of social and political barriers.[8] Welfare reform under President Bill Clinton in 1996 treated the presumed pathology, seeking to change the behavior of the impoverished, rather than addressing systemic problems of low-wage work, rising income inequality, or political disenfranchisement.[9]

O’Connor presents poverty research as “an inescapably political act: It is an exercise of power, in this instance of an educated elite to categorize, stigmatize, but above all to neutralize the poor and disadvantaged through analysis that obscures the political nature of social and economic inequality.”[10]

Whether a voyeuristic act or a political one, viewing poverty holds the poor up for our evaluation. They become the ‘others’ in the FSA photographs, whose hygiene and morals were freely questioned. In reality, however, they are the ‘strangers’ who cannot be effaced.

The photos of the FSA were clearly composed to create drama and remind us of our social responsibility.[11] But something is lost in the careful framing and cropping. We don’t see the full-color gone-with-the-wind landscape. Neither do we see the churning, whirling, overwhelming political economy that created the collapse. It’s ambient and unquestioned, and somewhat impossible to picture.

It’s also the substrate upon which social experimentation, including industrial agriculture and poverty analysis, occurs. It comes with a heavy social cost: dispossession.

“The growth of capitalism necessarily entails the destruction of modes of production based on the personal labor of independent producers.”[12] The effects are far-reaching, disrupting social stability at all levels.

Our political economic system runs on accumulation by dispossession[13], and it plows like a tsunami into all sectors of life: “These include the exacerbation of regional inequalities, generation of income inequalities at the farm level, increased scales of operation, specialization of production, displacement of labor, accelerating mechanization, depressed product prices, changing tenure patterns, rising land prices, expanding markets for commercial inputs, agrichemical dependence, genetic erosion, pest-vulnerable monocultures, and environmental deterioration.”[14]

The quote above, from Jack Ralph Kloppenburg’s excellent book, First the Seed: The Political Economy of Plant Biotechnology, deals directly with the commodification of plant material, but it rings true across all landscapes, rural, urban, and suburban. Our economic model is as pervasive and manipulative as Muzak at the mall.

This manipulative relationship does not show in the photos, nor in the poverty data analysis of the LBJ administration. But it does show in the widescreen version, where we see systemic problems that silence any arguments towards pathology of the poor.

Consider the viscerally vanishing landscape of the 1920s. It didn’t descend out of the blue onto flawed families of the plains. It was a devastated outcome just as they were.

Let’s widen our focus for a moment, and take a panoramic shot.

Industrial agriculture hit the plains in about 1873, in the wake of the economic panic that hit the US and Europe. Railroad companies, which had benefited from extensive speculative investments, suddenly ceased expansion projects. Among those companies was Northern Pacific, who found themselves at the end of the line in the Red River Valley, along the border Minnesota shares with North Dakota. There, they waited out the financial crisis by experimenting with large-scale agriculture, primarily in wheat.[15] They hoped their experiment would prove attractive to Germans and Swedes—in whose countries the company had established recruiting offices.

Their experiment worked, and the era of corporate farms was born. Great Northern Railroad soon followed suit, as did others.

These farms required seasonal labor as opposed to year-round work. They also required significant irrigation and soil enrichment with minerals collected off the farm. Smaller farms were crowded out, with the effects being felt even in New England.[16] In short, these corporate experiments supplanted the older model of self-sufficient family enterprises (i.e., not much money to be made) with an industrial operation full of dependencies (i.e., lots of money to be made).

Projected into the 20th century, the social effects have been considerable. In 1977, University of California-Berkeley plant physiologist Boysie E. Day addressed the American Society of Agronomy, and accepted the role of industrial agriculture in the social re-designing of America: “The agronomist has brought about the conversion of a rural agricultural society to an urban one. Each advance has sent a wave of displaced farm workers to seek a new life in the city and a flood of change throughout society.”[17]

This development was accompanied by a tightening bond between land-grant universities, government agencies, and private corporations, which Kloppenburg relates in great detail in First the Seed. This collusion was largely invisible to the public and remains so, but it drives most of the current agenda at revered agricultural institutions such as Cornell University.

The corporate farming model did not invent soil depletion. It did, however, greatly accelerate it.

Yale professor Steven Stoll, in his book Larding the Lean Earth, recounts the crisis that hit the United States within decades of the Revolution: its soils were completely exhausted by 1820. This depletion of farmlands among the original thirteen colonies was a major impetus for western expansion. Rather than improve the lands they already owned, many farmers hungered for the fertile fields of the Midwest, the west, and beyond. Some farmers and agriculturists fought this trend, pushing instead for responsible rejuvenation of the soil. The expansionist urge of the country favored westward movement.

Those who traveled westward took with them their unsustainable practices, as Stoll recounts. Their arrival in the Midwest and Great Plains coincided with another, and older, environmental shift: In 1725, French planters along the Mississippi River installed the first levee system. Doing so initiated a “complex geoclimactic relationship with about 41 percent of the United States,” states Alexis C. Madrigal, a contributing editor for The Atlantic.[18] Thirty-five thousand square miles of wetlands began drying out. By the time the directors of the Northern Pacific Railroad arrived, the land was dry enough for wheat—and for persistent cycles of droughts and floods.[19]

Lying within that progressively-drying Mississippi rivershed were Kansas and Oklahoma. Decades before the Farm Security Administration photographers documented the 1935 Dust Bowl, the first one—and many more–had already occurred.

Clarence Petrowsky, in his frequently cited Ph.D. Dissertation, “Kansas Agriculture Before 1900,” details the turbulence of the latter 1800s in the region. A land boom, lasting from 1875 to 1887, brought thousands of settlers into Kansas. They brought with them the same methods they had used in the Eastern US—those methods that had already worn out the soils in the Original 13. Kansas had far less rain, averaging 24” annually versus 32” in Pennsylvania. An unusual wet period, from 1882 to 1886, skewed peoples’ perception of the region, and they planted accordingly.

Drought arrived in 1893, and lasted for five years. It coincided with a world-wide depression (called The Great Depression, interestingly enough, until 1929). Those years saw multiple population upheavals, as farms could no longer support the families who worked them, which left a surplus of abandoned but cultivated land.[20] Over the state, farm production was down, as were farm receipts. Relief was being paid to farmers throughout the state, with counties also buying seed for the farmers. [21] Meanwhile, bad advice flowed like sand in an hourglass: “break up the prairie, plow the soil deep to make a reservoir” advised Kansas’ Agricultural Secretary Martin Mohler, in order to reverse the drought.

Not everyone could stay to witness the fantastic filling of those reservoirs. Many fled to Oklahoma, when the “unassigned lands” opened up for Anglo settlement in 1889. They brought their tried-and-true methods with them. Writing in 1938, USDA Assistant Soil Conservationist Angus McDonald tells a familiar story. Some highlights include:

“To the farmers of the Plains, wind erosion has been a serious problem for 50 years.”[22]

“Here also, erosion was experienced as soon as cultivation was introduced. Within 40 years of its settlement, the Territory had become one of the most critically eroded sections in the country. Probably nowhere in the world has so much destruction occurred in so short a period of time.”[23]

“The advice of farsighted individuals that much of the land was unsuited to cultivation was ignored… the inertia of tradition militated against such a revolution.”[24]

“In 1894 the sandstorms began again and recurred during several successive years. Reports for the years 1893, 1894, and 1895 are numerous. The sandstorms usually began in March or April and lasted for several days. Often they continued intermittently during the summer and into the fall. An April dust storm of 1895, accompanied by a 40- to 50-mile wind, evidently covered several counties. Clouds of dust obscured the sun and it was impossible to see halfway across the street.”[25]

“By the beginning of the century it was felt by some farmers that breaking the sod was a mistake.”[26]

The trend toward migrant and tenant labor also continued. McDonald reports that, “The whole area, however, is characterized by a progressive increase in tenancy.” The drastic shift in just two counties—Kingfisher and Logan—is alarming. In 1890, almost 100% of farms were cultivated by the owners. In 1900, only 67% and 59% respectively. By 1910, only 61% and 55% of owners were the cultivators of their own farms.[27] This means that 40 to 45 percent of those working the land had no ties and no security.

Blowing in the wind across those distressed farms is our political economy: “The agricultural system of the time in actuality placed a premium on soil destruction and a penalty on soil conservation. A program of soil conservation was not compatible with the greatest profits that could be derived from the land in a short period. The renter had, in many instances, mortgaged his crop and was forced to plant those cash crops that would pay the mortgage,” writes McDonald.[28]

The tenants, the migrants, who were created by the capitalistic urges of an industrializing agricultural system—these are the faces that we see in those FSA photos. Creative cropping, artistically, socially, and philosophically, eliminates capitalism from our view. We see only the folly of the plowman and the dirty, torn clothing of his dispossessed workers.

So where is the pathological problem, if indeed it exists?

The Dust Bowl, Depression, and mass displacement of the 1930s were not sudden aberrations. There were plenty of precedents, along with ample warning. Yet the poor—whether they be tenant farmers, migrant agricultural workers, miners, railroad laborers, or textile workers—continually take the brunt. Could it be that the system in which they live and labor is the pathological one?

As Alice O’Connor states in a recent column, “The problem of poverty cannot be resolved without addressing the deeper inequities of race, class, gender, geography, and power—a lesson overshadowed by the myth of a ‘culture of poverty’ that gripped policy elites in the 1960s and continues to thread through popular and academic discourse to this day.”[29]

Unfortunately, however, “contemporary poverty knowledge does not define itself as an inquiry into the political economy and culture of late twentieth-century capitalism.”[30] Don’t implicate the system, just analyze the data. Objectification of the poor happens in safe and sterile isolation. To do anything else would be un-American.

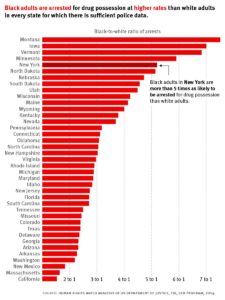

However, images continue to fly across our screens at blinding speed, reminding us that we must act. We are in the midst of the largest refugee crisis the world has ever seen. Poverty is being criminalized. African American men are being incarcerated at an alarming rate. The people of Flint, MI, have become irreparably ill by drinking water from their home taps. We have sufficient reason to question our economic and political philosophies. It seems as simple as asking, “Should we be plowing up all this dry land?”

Referencing Susan Sontag, Cara A. Finnegan says in her introduction to Picturing Poverty: “The FSA photographs functioned to ‘help people take possession of space in which they are insecure.’ And the images served as a tool for power.”

Images of dispossessed workers, urban poor, and displaced refugees help us to fight that tendency spoken of by Alice O’Connor, to push against the stigmatization and neutralization of the poor. They help us to see the true political nature of social and economic inequality.

In looking past the composition and cropping of the images, we might see despair, but we can also see hope. In a recent Democracy Now! interview with Amy Goodman and Juan Gonzalez, educational pioneer and critical theorist Henry Giroux expressed a spirited anticipation:

“We see young people all over the country mobilizing around different issues, in which they’re doing something that I haven’t seen for a long time. And that is, they’re linking these issues together. You can’t talk about police violence without talking about the militarization of society in general. You can’t talk about the assault on public education unless you talk about the way in which capitalism defunds all public goods. You can’t talk about the prison system without talking about widespread racism. You can’t do that. They’re making those connections.

“But they’re doing something more: They’re linking up with other groups. If you’re going to talk about Flint, if you’re going to talk about, it seems to me, Ferguson, you have to talk about Palestine. If you’re going to talk about repression in the United States, you’ve got to figure out how these modes of repression have become global.”[31]

Giroux’s words, prompting us to widen our frame of vision so that we see beyond the cropped image, provide an energetic response to the call of Iain Chambers, which is worthy of repeating.

”That stranger, as the ghost that shadows every discourse, is the disturbing interrogation, the estrangement, that potentially exists within us all. It is a presence that persists, that cannot be effaced, that draws me out of myself towards another. It is the insistence of the other face that charges my obligation to that ‘strangeness that cannot be suppressed, which means that it is my obligation that cannot be effaced’.”[32]

So we have a lot of work to do.

(This essay accompanies Peace Meal Supper Club™ #18: Aperture. To read more about this event, please click here. Also, read about the album that inspired this event by clicking here.)

____________________________

[1] Cara A. Finnegan, Picturing Poverty: Print Culture and FSA Photographs (Smithsonian Books, 2003), xiv.

[2] I’m summarizing a lot of the information presented in Finnegan’s absorbing work. Consider giving it a read.

[3] Finnegan, 198.

[4] Finnegan, xv.

[5] Lyndon B. Johnson: “Annual Message to the Congress on the State of the Union.,” January 8, 1964. Online by Gerhard Peters and John T. Woolley, The American Presidency Project, accessed October 16, 2016, http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/?pid=26787.

[6] Alice O’Connor, “The War on Poverty at Fifty,” Institute for Public Accuracy, January 7, 2014, accessed October 16, 2016, http://www.accuracy.org/the-war-on-poverty-at-fifty/

[7] Alice O’Connor, Poverty Knowledge: Social Science, Social Policy and the Poor in Twentieth Century U.S. History (Princeton University Press, 2001), 15.

[8] O’Connor, 16.

[9] O’Connor, 4.

[10] O’Connor, 12.

[11] Finnegan, xv.

[12] Jack Ralph Kloppenburg, Jr., First the Seed: The Political Economy of Plant Biotechnology, 2nd Edition (University of Wisconsin Press, 2004), 38.

[13] Summarized in modern Cliff Notes form at the friendly neighborhood Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Primitive_accumulation_of_capital#David_Harvey.27s_theory_of_accumulation_by_dispossession

[14] Kloppenburg, 7.

[15] Cindy Hahamovitch, The Fruits of Their Labor: Atlantic Coast Farmworkers and the Making of Migrant Poverty, 1870-1945 (University of North Carolina Press, 1997), 15.

[16] Hahamovitch, 19.

[17] Kloppenburg, 6.

[18] Alexis C. Madrigal, “What We’ve Done to the Mississippi River: An Explainer,” The Atlantic, May 19, 2011, accessed July 22, 2015, http://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2011/05/what-weve-done-to-the-mississippi-river-an-explainer/239058/

[19] Christopher Morris, Big Muddy: An Environmental History of the Mississippi and Its Peoples from Hernando de Soto to Hurricane Katrina(Oxford University Press, 2012), 169-170.

[20] Clarence Leo Petrowsky, “Kansas Agriculture Before 1900” (Ph.D. diss., University of Oklahoma, 1968), 202.

[21] Petrowsky, 203.

[22] Angus McDonald, Erosion and its Control in Oklahoma Territory (Miscellaneous Publication No.301, U.S. Department Of Agriculture, 1938), 1.

[23] McDonald, 2.

[24] McDonald, 5.

[25] McDonald, 8.

[26] McDonald, 12.

[27] McDonald, 7.

[28] McDonald, 8.

[29] Alice O’Connor, “The War on Poverty at Fifty,” Institute for Public Accuracy, January 7, 2014, accessed October 16, 2016, http://www.accuracy.org/the-war-on-poverty-at-fifty/

[30] O’Connor, Poverty Knowledge, 4.

[31] http://www.democracynow.org/2016/10/14/is_trumps_rise_a_result_of

[32] Iain Chambers, Migrancy, Culture, Identity (Routledge, 1994), 6.